Rating: ❤❤❤❤❤

There is all a woman in your compass, my poor sister.

– Zenobia, The Blithedale Romance

Marilyn Monroe appeared to me last night as a kind of fairy godmother.

– Sylvia Plath diary entry

Take me as I am,

take me, baby, in stride.

Only you can save me tonight...

You let me in, don’t leave me out

or leave me dry.

Even when I’m alone

I’m not lonely…

– Lana Del Rey, “God Bless America and All the Beautiful Women In It”

“Dumb But Not Dumb”

In a 2013 E! News interview actor Megan Fox explained her decision to remove a tattoo of Marilyn Monroe from her right arm:

I started reading about her and realized that her life was incredibly difficult. It’s like when you visualize something for your future. I didn’t want to visualize something so negative. She wasn’t powerful at the time. She was sort of like Lindsay [Lohan]. She was an actress who wasn’t reliable, who almost wasn’t insurable…She had all the potential in the world, and it was squandered. I’m not interested in following those footsteps.

Annnnd she’s not following in Marilyn’s Monroe’s footsteps. Not even close. Nor is she anywhere close to lovely Lohan’s level. If difficulty, negativity, unreliability and lack of insurers’ confidence disqualify someone as inspiration or honorable memorialization on one’s skin, then history has a dire shortage of role models. The tattoo is probably gone by now, but if I’d had the time (and her phone number) back then I would’ve urged Ms. Fox to reconsider the tarnished star and accept her image as an uplifting, important symbol, not a shallow, wasteful shame.

Marilyn Monroe’s tattoo-worthy body may be the most recognizable, revered, fetishized and famous body (which includes her iconic face) in human history. And for good – not bad – reason. Marilyn’s body was just as much her as the person behind the persona. (If I hear a sermon on preferable “inner beauty” once more I’m going to combust!) Oscar Wilde said that beauty is its own kind of genius, and the artist formerly known as Norma Jeane was that kind of genius. Her tragedy didn’t lie in some imprisonment of perpetual failure to live up to the world’s lust. She did that, and still does. Daddy issues weren’t the tragic flaw either. Who doesn’t have daddy issues? Debbie Harry, whose look and mystique exist almost exclusively because Marilyn existed, wondered if “the common denominator” they shared was a “need for immense doses of demonstrative love.” Who doesn’t need that? We’re all deprived children. And deferred artistry wasn’t the killer. Countless serious actors would’ve mass-murdered to get even an imperceptible fraction of the range of roles she had. It was obvious then and remains obvious now that Marilyn had thespian potential that brought a buoyant but brimful, burning gravitas to every film in which she starred. Her gradual disintegration and ultimate demise came from a fatal cocktail of familial madness, foolish trust in dirtbags and chemical addiction.

Watch only George Cukor’s Let’s Make Love and, if you’re warm-blooded, half-awake and at least half-human, you’ll understand why Marilyn Monroe is special, legendary and revered as semi-divine. Yes, she had underestimated, underused talent, but she was primarily (priMarilynly) a unique and truly transcendent body, a gift of fortune that should be neither downplayed nor demeaned. Unlike, say, Rita Hayworth, the real Marilyn in bed wasn’t light-years away from the projected erotic promise. Rita famously said that lovers expected to wake up with her Gilda character rather than her relatively mundane self. I’d bet that, sexually speaking, Marilyn dusked and dawned seamlessly. I’d bet the Brooklyn Bridge that her allure was more emanation than projection. As a savant of the human body, she knew both its intricate and blunt wants and needs, and she knew exactly how to leverage her own body to ply, play, produce pleasure, please and even plead.

There has been and still is much speculation on the degree to which Marilyn’s reputation as a ditzy blonde was accurate, and the speculation tends to involve both underestimation and overestimation, which are both problematic. Undermining, doubtful terms in regard to her intellect and talent have been dominant since her demise, but some worthy folks have claimed otherwise. Saul Bellow said Marilyn “conduct[ed] herself like a philosopher,” and Professor Sarah Churchwell calls her “a greater Gatsby” rather than classifying her as a Dumb Blonde. Though Marilyn had much ditz in her system, I tend toward the camp that suspects that she consciously did what Lester Bangs thought the Ramones’ gimmick was: “sort of playing with the concept of being dumb but not dumb.” Her intellectual appetite was certainly hefty: she attended UCLA classes at night, studied history and literature, read top-notch books and even wrote some often poignant poetry. “But once you start using sex appeal as a way of getting attention,” Bangs wrote of Debbie Harry in Blondie, “it’s not always easy to draw the line and have people appreciate your other talents.” That’s true. Camille Paglia referred to Marilyn as an “exaggerated, vulnerable icon.” That’s half true (the second half), but a born exaggeration can’t be exaggerated further.

Inconveniently Interruptive Interludial Interview Link: “A Kind of Pascal’s Wager”

Back in 2016 I conducted a SubtleTea interview with the always-worth-reading Megan Volpert for her 1976 book, and I, as semi-defender and semi-Devil’s advocate, challenged her about something she wrote in regard to Marilyn’s brain and a Marilyn/Debbie Harry dichotomy. I think it’s worth offering readers a choice to read a pertinent excerpt via the following link, since I’m never immune to digression. (Read the interview excerpt here – or scroll to the end of the review for the addendum.)

“Dumb But Not Dumb” continued

During his period of hostility toward Marilyn, before realizing her wondrousness, Nunnally Johnson (scriptwriter for Marilyn-involved movies O. Henry’s Full House, How to Marry a Millionaire, and Something’s Got to Give) correctly identified her as “a phenomenon of nature, like Niagara Falls or the Grand Canyon.” Except she surpasses both water and rock, as all beautiful people do. No magnificent landscape can compete with pulchritudinous humans. We ordinary people, however, are mere noisy, damp dust.

Speaking of Niagara Falls, in her characteristically incisive 1973 review of Norman Mailer’s Marilyn biography, titanic critic Pauline Kael “the tawdriness of ‘Niagara’…in which her amoral destructive tramp – carnal as hell – must surely have represented Hollywood’s lowest estimate of her.” The Niagara role (and the one in Don’t Bother to Knock, I think) showed that she had, to use Kael’s words, “mean, unsavory potential” – and Marilyn must have seen and shrewdly willingly embraced the not-so-subtle, bubblegummy cinematic parallels, analogies, metaphors and recapitulations of her own persona, mentality, biography and pathology. The blur between her private and public lives seems so blurry that it seems that Marilyn consciously and/or naturally facilitated a weird cross-pollination of fictional and factual sentiments, tropes and scenarios (into and out of her movies) that cohered into the incoherent mythological figure we still wonder about and Freud out over to this day.

Kael mocked psychoanalytical interpretations of Marilyn, particularly Mailer’s, instead settling on a blunter, rawer assessment: Marilyn’s “extravagantly ripe body bulging and spilling out of her clothes” and her contradictory but deftly alternating “childlike tenderness” and “shrill sluttiness” that mesmerized men. This is a sounder summing up. As for identifying the essentializing “Rosebud” of Norma Jeane’s life, I’m not as skeptical as Kael, so I neither castigate nor enthusiastically embrace psychoanalytical theories.

I hardly ever desire neat encapsulations of biographies’ subjects. As Parker Posey writes in her recent memoir, You’re on an Airplane: “If I didn’t believe in the complexities of another’s heart and soul…then I really would have to weave baskets.” Usually it’s better to let the top spin and appreciate the colorful blur rather than fondle and inspect its specific structure. Norman Mailer wondered “whether a life like [Marilyn’s] is not antipathetic to biographical tools,” which is quite correct. This is why Kael’s eye rolling is justified and why the flighty insights of so many armchair shrinks are simultaneously worthwhile, and why I can distill Marilyn’s wild, weird, womanly, woeful existence down to, literally, the flesh – while also accepting that, if Alfred Hitchcock was right to metaphorize Grace Kelly as a “snow-covered volcano,” then what we don’t know of Marilyn Monroe must be miles of unseen turbulent magma.

“I don’t have a body,” wrote the great Christopher Hitchens as he was dying of cancer, “I am a body.” I appropriate that sobering declaration to emphasize the body’s importance (if not primacy), and, as much as I tend to resist the “existence precedes essence” thing, I think the uplifting visceral reaction we have when viewing beautiful bodies is just as impactful as our recoiling from corpses. Which is why the expiration of Marilyn Monroe’s living-legend body is radically horrific, in contrast to, say, the future cessation of my life. Yes, I’m more than implying that the death of heavenly-bodied people is palpably sadder than that of the ordinary-bodied. Because there seems to be a glimmer of material transcendence, of a better shot at immortality, of a superheroic erotic persistence in bombshells and hunks, so when even those fortunate frames wither or are cut down by the Reaper, the affront seems more extreme, the obliteration of incarnate art feels more brutal and insulting. Alex Kuczynski says in Beauty Junkies: “Yet beauty speaks to such basic, deep longings, that our search for it remains the most insistent force in our lives. It is an expression of the divine, a symbol we hold up against the inevitable humiliations of mortality.”

Let’s be honest. Any fan and/or ogler of Marilyn has virtually ravaged her to some degree on the virtual casting couch; the complicity of hungry eyes spans the globe. And our fascination isn’t due to her ambition, her talent, her voice or what she said with her voice: it’s with that body and that face and that cherry-in-snow smile, that platinum hair, how she fit – or delightfully didn’t quite fit – into clothes. “She is like nothing human you have ever dreamed of,” wrote Esquire writer Alice McIntyre back in the day. That’s because Marilyn wasn’t a dream in the first place. She was the real deal: proof that the sleep of reason – to borrow from Goya – produces Earth angels as well as monsters.

“The Most Womanly Woman”

Arthur Miller, one of Marilyn’s unlikely (and grossly lucky – and gross) lovers, called her “the most womanly woman I can imagine” and “a lodestone that draws out of the male animal his essential qualities.” Likewise Pauline Kael said that “her mixture of wide-eyed wonder and cuddly drugged sexiness seemed to get to just about every male; she turned on even homosexual men.” “Of course, what’s inside matters,” Helen Gurley Brown wrote in Sex and the Single Girl, “but a beautiful outside has a way of making the most rational, charming and intellectual man go all apart.” This is something Naomi Wolf complains about in The Beauty Myth” (which, despite its brilliant importance, tries to kill too many targets): “Both men and women…tend to eroticize only the woman’s body and the man’s desire.” (Well, duh. It’s not all manufacture, not all myth.) A dictionary-size volume could be filled with quotations about Marilyn’s mammal magnetism and effortless hypnosis of just about anyone whose gaze fell into her primordial-force orbit and felt the fundamental erotic pull from her magmatic core.

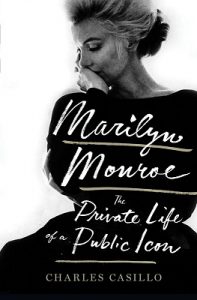

A biographer who seems to get this important central factor in Marilyn’s living and posthumous fame is former actor, playwright and author Charles Casillo, whose new book, Marilyn Monroe: The Private Life of a Public Icon, presents the woman in both the flesh and the flash, in sickness and in hell, in and out of love – without sacrificing respect for the integral carnality at the heart of it all. “My research of Marilyn Monroe started as a child when I became fascinated with a photo I saw of her in a magazine,” he says in the book’s Acknowledgements. “I have been following that trail ever since.” How else could an appropriate introduction to Marilyn Monroe happen but by sight alone? Her singing wasn’t a test-of-time endurer, and her poetry never rose to the level of literary peerage; from her career’s beginning she relied on the gaze of others. Marilyn was and is a visual phenomenon, a scopophilic idol. Perhaps the bluntest and most illustrative anecdote Casillo shares in the book is Groucho Marx’s remark to her (during the filming of Love Happy, I assume): “You have the prettiest ass in the business.” Also, years later Groucho recalled: “Boy, did I want to fuck her.” This kicks my mind over to what Paul Burston said about Marilyn-emulous Debbie Harry: “You either wanted to fuck her or be her.” Sure, there’ve been many bombshells, but Marilyn is a measurement standard for them all, like the demarcation between B.C. and A.D.

“She had a perfect body,” writes Casillo, without irony or cynicism, “and she flaunted it the way some might flaunt a stellar education, or family connections, or great wealth. It was her calling card.” This volumes-speaking line refreshes with its rare erotophobia-free legitimization of physical excellence. Rather than casting her as a rampant elemental force (like Niagara Falls), Casillo stresses Marilyn’s conscious leverage of the fission she sparked in the loins and loves of others. Later in the book, in a passage about the affair with JFK, Casillo reveals a drastically unsurprising but telling fact: “Somewhere in the course of their pillow talk, the conversation turned to anatomy – a subject on which Marilyn was very knowledgeable and had been for a long time: The human body was one of her main fascinations.” (This reminds me of what Manet said of Monet back in 1874: “He is the Raphael of water. He knows it in its movements, in all its depths, at all its hours.”) The body was both her hobby and her craft, ever since puberty, really – and I deny that her body was “her prison,” as Gloria Steinem wrote. On the contrary, Marilyn’s flesh was a freeing key. “Being beautiful meant attention and power and maybe even love,” writes Casillo. And he sums up her awareness and fundamental wily authority in this line: “She was becoming aware of her female power – and she reveled in it.” “The world became friendly,” Marilyn herself said of the gained awareness. “It opened up to me.”

In “Marilyn Monroe: The Woman Who Died Too Soon” (1972), Steinem made the not-rocket-science point that “in films, photographs, and books, even after her death as well as before, she has been mainly seen through men’s eyes.” Likewise, Casillo notes that even as late as the twilight of her career and life, “the lust of men was what had always given her confidence.” Much has been written and speculated on about this being a deep-seated longing for adoring father figures, but, despite its plausibility, I find the theory worn and boring. Instead, I attribute much of Marilyn’s apparently ceaseless attraction to and flirtation with men to a simpler instinct: a compelling, if not obsessive, discipleship in traditional gender binarism, the starkly delineated feminine/masculine duality that delighted and drove her. Nunnally Johnson said that she had “learned how to throw sex in your face,” but for Marilyn that targeted face had to be unquestionably male.

When given the chance to star in a movie version of George Axelrod’s Goodbye Charlie Marilyn, repulsed, refused. The immutability of femininity and masculinity in her worldview is described by Casillo:

She couldn’t bear the thought of her femininity being questioned. Obsessing over homosexuality during a psychiatric session with Greenson, Marilyn expressed rage when he informed her that there was something feminine and masculine in both genders, and she became mortified that anything masculine might be perceived in her.

Her close friendship with Pat Newcomb was so close that lesbianism was suspected by many observers, and, though Newcomb denied it, mother-figure Susan Strasberg claimed to have noted a “somewhat sexualized” relationship between the two. “In those pre-sexual-liberation days, what had come to terrify Marilyn was the confusing of genders,” writes Casillo. “For her there was a clear line of masculine and feminine behavior. She was paranoid about anyone finding anything masculine in herself.”

“The real female should be partly male,” Bette Davis said to interviewer Shirley Eder in 1963, “and the real male should be partly female anyway.” Conversely, in a 2017 Hollywood Reporter interview Camille Paglia commented on alternating phases of androgyny’s popularity: “World civilizations predictably return again and again to sexual polarization, where there is a tremendous electric charge between men and women.” Without meaning or wanting to get into a whole dissertation or debate about the gender binary, gender fluidity and such, I will say that I think a big part of the secret to Marilyn Monroe’s psychology and public behavior is a sincere appreciation for the half-circle view of male and female chemistry: the sexual yin-yang, lock and key, hand/glove, puzzle – whatever you want to call it. And perhaps her apparently virulent reaction to perceptions or realities to the contrary is due to her conclusion that, for whatever reason of fate, she had been biologically destined as a globally recognized representative of femaleness itself and took the magnificent burden quite seriously.

So, of course, “the lust of men” was crucial to Marilyn’s sense of self-worth and effectuality. It both emboldened her and upset her during tailspins of age-dread. As Casillo puts it, “age stalked Marilyn like a demon,” and so, especially when past the halfway point in her thirties, she would lose herself in mirrors, “perfecting the reflection, doing her best to live up to the mythological creature she had become.” Perhaps a stanza from her deeply personal poetry sums up the burdensome situation:

Where his eyes rest with pleasure – I

want to still be – but time has changed

the hold of that glance.

Alas how will I cope when I am

even less youthful –

Sure, the diminution and ultimate loss of physical beauty is, without a doubt, quite stressful and sad, as melancholic as the passing of a dear era, but I contend that it’s better to have been gorgeous than to have never been gorgeous. And it’s better to be gorgeous and underestimated than to be homely and underestimated, at least as far as stardom goes. Sometimes as far as genius goes too. Margaret Fuller, a magnificent thinker, writer and historical powerhouse, couldn’t stand her lack of good looks. “I cannot help but wearying myself of this ugly cumbrous mass of flesh,” she lamented. “I hate not to be beautiful, when all around is so.” Being respected for her mind and craft didn’t fulfill Fuller. I guess the grass-is-greener parallax is at work here, for the inverse happens just as severely in those who resent their own beauty as cumbrous and long for mental, creative merit instead.

When I consider the frustrations of Marilyn Monroe, I can’t help but think of Hedy Lamarr, who also struggled with a disconnection between her loftier ambitions and the public’s perception, perhaps more acutely than Marilyn. The two stars share many parallels, but, unlike Marilyn, Hedy disliked even identification of herself as a woman (coupled with concealment of Jewish heritage), according to documentarian Alexandra Dean. To Hedy, her amazing face was a “misfortune,” an irremovable “mask” that she had to tolerate, that she cursed. She thought her face ruined due recognition for her intellect, which extended into remarkable ideas and inventions during spare time. “Except in the matter of her beauty, which she valued least of all, people regularly underestimated her,” writes Richard Rhodes.

However, like Marilyn, Hedy wasn’t blind to the potent usefulness of her “curse.” As actor John Fraser put it, Hedy “had been fawned upon, indulged and exploited ever since she had reached the age of puberty,” and, to quote Stephen Michael Shearer, “even as a child Hedy realized what her visual attributes could achieve for her.” But that fact was a source of tension for her all her life: beauty as an obscuration, and then obscurity replacing lost beauty later on. Marilyn, on the contrary, “reveled” in her looks’ power, as the earlier Casillo line says. What both women shared was a desire to branch out or to achieve recognition beyond their genetic good fortune and star chemistry. Hedy’s expressed desire “to do certain things on the screen that will mean more to me personally, my inner feelings, my own ambitions” could very easily pass for something Marilyn might have said. When Robert Osborne said that Hedy “had that curse that all those beautiful women had – nobody could see beyond that,” he reiterated the same basic assessment that countless folks had made about Marilyn Monroe and many other Earth angels – and will until time’s end. Both women wished to excel more at the craft of acting rather than dialing it in with their appearances, and not being taken seriously critically galled them. Lana Turner once said that Hedy sucked at acting but deserved credit as “the most beautiful woman.” Likewise, Marilyn’s persona and hips were treasured much more than her thespian chops.

Sure, many might consider the gulf between Hedy’s public image and her intellectual/scientific passions to be wider than Marilyn’s, teaming up with George Antheil in an invention frenzy and belting out detailed ideas such as breakthrough spread-spectrum technology utilized by the Navy, but Marilyn was much more of a reader and a curiouser cultural dabbler/explorer – and she was…get ready to groan…headier about acting. I think Marilyn had more of a genuine artist in her, and I think her frustrations and pain were of the artists’ brand. But still. She excelled as living art, as bathetic (and perhaps offensive) as that term is.

Just as a magnificent monument or a lovely painting penetrates straight to our bones with its instant sublimity, so does a magnificent, lovely body and a mind-melting face. Perhaps Magritte put it best in The True Art of Painting (1949), when he touted his painterly goal of “a pure visual perception of the exterior world by means of sight alone” and vision’s primacy over meditation, which seems in accord with Susan Sontag’s focus on “the luminousness of the thing itself” rather than meddlesome hermeneutics. Contrarily, Marcel Duchamp mandated interpretation, rejecting “too great an importance given to the retinal.” (He preferred the urinal.) I tend to prefer visuality to so-called “inner beauty.” If neither Hedy Lamarr nor Marilyn Monroe could embrace their aesthetic might fully, I’ll embrace it for them. (Maybe if most celebrities who feel cursed with good looks would change their outlook if given the chance to see what their lives and careers would be like if those good looks had never existed, like George Bailey observing a George-free world in It’s a Wonderful Life.)

And it’s foolish to try to embrace body aesthetics without the corollary erotic. Far from being an oversexed nation, I think America is prone toward a virtue-signaling frigidity that either neglects or rejects sexuality’s superior power, particularly pooh-poohing gender-specific dynamics and especially any peculiarity of female eroticism. As a Marlene Dumas poem goes, “one cannot paint a picture of/or make an image of a woman/and not deal with the concept of beauty.” Going farther, Wendy Steiner calls woman/beauty disassociation “effectively misogynistic.” Downplaying a woman’s sexual profundity is like traversing an active volcano’s caldera and denying the deadly danger of spewing lava, or it’s like treating a volcano glow as mere candlelight.

Speaking of candles, in his famous ballad to Marilyn Monroe, “Candle in the Wind,” Elton John uses the frailness-implying dying-candle metaphor for typical (religious/secular Manichaean) virtue-signaling about the alleged shallowness of skin: “From the young man in the twenty second row/Who sees you as something more than sexual.” Oh, come on! Beauty is not just “skin-deep;” the willing spirit isn’t worthier than the “weak” flesh: beauty has fathomless depth, and the flesh is mighty.

“Endlessly Vulnerable Child”

Marilyn’s despondent spells, her hang-ups, and her fears and sublimations have been categorized as darkness, but I consider the woman essentially a creature of light and an evoker of light for others – including us, and I’m fascinated by the profound light metaphors that were and are so often used about her. “I could massage her in the dark because her body gave off light,” said masseur Ralph Roberts. Henry Hathaway, who directed Marilyn in Niagara, said that she was “bright, really bright…naturally bright.” And in reference to her role as Lorelei Lee in Gentleman Prefer Blondes, Charles Casillo writes that “she absolutely glows. Her inner light is so radiant that it’s difficult to believe anything dark ever happened to her – you don’t want to believe it, yet you know there’s darkness there.” And later: “Perhaps her darkness began the very moment she was conceived…”

This darkness that so many folks focus on seems to mostly originate from a fundamental loneliness that Marilyn found intolerable. As with almost anything, Bette Davis, who became acquainted with her during All About Eve’s production, speaks up again in her quotable quote about it: “…I think now that she was as lonely as I was. Lonelier.” Casillo goes as far as to call loneliness “her biggest enemy.” Well, why not consult her confessional poetry again?

Alone!!!!!

I am alone – I am always

alone

no matter what.

Thanks to the exhaustion that loneliness, anxiety and depression bring, Marilyn needed a lot of sleep. “Her entire life revolved around sleep, and how to find new ways to do so,” writes Casillo. An absolutely unsurprising revelation, considering the common pattern of depression, exhaustion and escapism found in too many people’s – particularly celebrities’ – lives. The one thing that’s pretty constantly factual for adored individuals is their personae’s simultaneous power and inadequacy, along with other familiar woes: mental health and/or bodies in ruin, and loneliness at unbearable levels. The latter is especially suspicious because we tend to half-disbelieve that a celebrity who is worshiped by millions of people and whose image appears everywhere can feel lonely – and actually be lonely, but it’s more common than rare. And perhaps the most insidious affliction is the agony of evasive sleep. It’s no wonder that sleep-deprivation is a basic form of torture and can lead the breakdown of personality and will. Anyone who has suffered from insomnia even periodically knows the perfect destructiveness of it. What makes loneliness, anxiety and depression so much worse is the disruption or lack of crucial sleep and the inaccessibility of its recuperative effects.

Two key pop legends in their own time, Elvis and Michael Jackson, are heartbreaking examples of agonized non-sleepers. In Being Elvis, Ray Connolly returns to sleep’s elusion of Elvis several times, emphasizing the pitiful fact that “he “craved sleep, no matter how it was achieved,” which caused a perpetual cycle of relying on abused prescriptions to speed up and slow down, the same chemical imprisonment in which Michael Jackson – and Marilyn Monroe – spun. In despair one night, Elvis wrote: “I feel so alone now…I would love to be able to sleep…I will probably not rest tonight…Help me, Lord.” You get the picture. Such weary feelings of being at the end of one’s rope don’t involve a desire for actually being at the end of a rope. Instead, it’s a softer, shimmering despair that’s not Metallica’s “Fade To Black” but The Smiths’ “Asleep,” which may be the profoundest and bittersweetest expression of longed-for escape by sleep or eternal sleep:

Sing me to sleep,

sing me to sleep,

I’m tired and I,

I want to go to bed.

Sing me to sleep, sing me to sleep,

and then leave me alone.

Don’t try to wake me in the morning,

’cause I will be gone.

Don’t feel bad for me.

I want you to know:

deep in the cell of my heart

I will feel so glad to go…

Of course, Marilyn’s desperate pursuit of oblivion can easily be interpreted as a quest to regain prenatal security and peace, which is especially metaphorically convenient when one buys into the common view of Marilyn as a sort of perpetual child: “childlike sex goddess” (Gloria Steinem), “child-girl” (Norman Mailer), “beautiful child” (Capote) and even “baby whore” (Pauline Kael). But, then again, are any of us free of the wombic beckon? Who out there has fundamentally transcended childhood’s imprint? Another selection from Marilyn’s poetry:

Everyone’s childhood plays itself out

No wonder no one knows the other or can completely understand.

Her mother was Gladys Pearl Monroe, who, as Casillo puts it, “like her mother Della, was a weird mixture of modesty and religion with hedonistic passions.” Gladys’ mess of a life brimmed with abuse, divorce, stress, distress and instability. Gladys landed a job cutting negatives at Consolidated Film Industries, an auspicious industry when her future daughter’s destiny is considered, and there she befriended a Grace McKee, who “swept [her] into a seductive fantasy lifestyle based on the movies stars she avidly read about.” Gladys married the religious Martin Mortensen, but became bored with him a little over a half year later, left in search of wilder satisfaction and let a Charles Gifford, who is believed to be the biological father of the girl who was born in 1926 and would be named Norma Jeane.

Norma Jeane inherited the name Baker due to Gladys writing “baker” as the father’s job – Baker, of course, being her first husband’s surname. Norma Jeane lived with her grandmother Della for a while before guardianship went to foster parents Wayne and Ida Bolender, who were strictly religious pent-up Pentacostals. Once again portent of eventual stardom arose in Ida’s guilt-reeking diatribes to the girl. For instance: “If the world came to an end with you sitting in the movies…[Y]ou’d burn along with all the bad people. We’re churchgoers, not moviegoers.” “Ida also denounced the sin of vanity,” Casillo reveals. “She railed against women who took their time over their appearances or who seemed to be boastful about their looks.” Little did uptight Ida know who her passive ward would become before the eyes of Earth’s population someday. But Grace McKee knew. Obsessed with Jean Harlow but realistic about her advanced age’s preclusion of her ever becoming another Harlow, Grace predicted future stardom for potential-rich Norma Jeane.

There’s no doubt that during her famous years Marilyn fretted constantly over her appearance, but one wonders if she ever got to the point of hubris about it. Whether or not Marilyn was indeed vain or not seems to be an ambiguous thing. On one hand, in his book Casillo says that she had “a form of narcissism without vanity” – but later on contradicts with the phrase “for a woman as vain as Marilyn.” There’s a similar Rashomon discrepancy between Lauren Bacall’s “she had no meanness in her – no bitchery” and Peter Lawford’s “Marilyn could also be a mean little bitch” (as C. David Heymann reports in A Woman Named Jackie). No big deal, really. If anyone deserved to be excused for vanity and meanness, it would be Marilyn Monroe, right? Really, it’s impressive that Marilyn was so apparently affable and not radically, if not perpetually, bitchy.

Grandma Della finally had a psychotic breakdown, and, later, Gladys’ insanity intensified into a paranoid-schizophrenia diagnosis. Both women ended up in mental institutions, a fate feared by Marilyn for the rest of her life. Needless to say, Norma Jeane’s youth was capricious, which didn’t improve when she reunited with her deranged mother. All the while she longed for her father and, to use Casillo’s words, “would spend a lifetime looking for this man in others, wanting to know him, loving him, passionately wanting him to love her back.” Her entire too-much-talked-about father-figure pathology is summed up better than any mental professional could hypothesize or diagnose in the innuendo-rich lyrics of Cole Porter’s “My Heart Belongs to Daddy,” which Marilyn performs superhumanly in Let’s Make Love (a scene that never fails to feverishly enthrall me): “So I want to warn you laddie,/though I know that you’re perfectly swell,/that my heart belongs to Daddy,/’cause my Daddy, he treats it so well.”

“As an adult, still wanting to be rescued by her father, she would attempt to re-create him in the men in her life,” Casillo includes in a salacious footnote. “At a Manhattan party Marilyn confessed that she longed ‘to put on a black wig, pick up her father in a bar, and make love to him. Afterward she would ask, ‘How do you feel now to have a daughter that you’ve made love to?’” (Okay, Freudians, I’ll give you that one.)

Fatherless and surrounded by dysfunctional women, Norma Jeane escaped the detrimental influence of her mother again when she moved in with George and Maude Atkinson, who were refreshingly lax, fun and kind, and provided some respite from chaos. But chaos tends to overpower peace, and, according to Marilyn later on, she fell victim to sexual abuse by a fellow boarding-house resident. Though the testimony is unspecific, one stark detail is that the molester repeated “Be a good girl” during the ordeal, which is an eerie coincidence in regard to the earlier puritanical guilt-giving from both Ida Bolender and Gladys. Just how many abuse incidents there were is unknown, and though cynical Pauline Kael suspected that during the 1950s Marilyn “was embroidering that raped and abused Little Nell legend that Time sent out to the world in a cover story,” Casillo contends that “much of her adult behavior has the characteristics of someone who had been sexually abused in childhood: shame. Low self-esteem. Depression. Nightmares. Substance abuse. Suicidal thoughts.”

Just as money comes to money, abuse somehow finds the abused (or vice versa). Grace’s new husband, “Doc” Goddard, molested Norma Jeane, so the girl was sent to an orphanage in 1935, where she developed a (symptomatic?) stutter. This time sounding a little like Kael, Casillo writes that Norma Jeane’s emotional distress caused her “to magnify the degradation she had been forced to endure there,” her hyperbolic habit helping her to “seem a canny publicity machine who made up stories to create sympathy from her adoring public.” Despite her description of the place, the orphanage was, in reality, humane and well-managed. Grace regained custody of Norma Jeane in 1937, danger to the girl apparently gone – until a cousin molested her. From there Norma Jeane went to live with one Aunt Ana Lower, in L.A. When Ana became too ill to provide effective supervision, Grace worked at arranging a marriage-bound romance between Norma Jeane and a Jim Dougherty, who indeed foolishly married each other.

The road to being the next Jean Harlow opened when Norma Jeane met Emmaline Snively, who was affiliated with a modeling agency via a photographer named David Conover. As if fulfilling Grace McKee’s prophecy, Snively inspired the iconic bleach-blonde look for Marilyn Monroe-in-the-making. The snowball snowballed on. Ben Lyon, a casting agent for 20th Century-Fox, changed Norma Jeane’s name to Marilyn, and Marilyn herself chose her mother’s original surname, Monroe. The reinvented creature, the renamed character, the germinated irresistible paramour outgrew poor Jim Dougherty, of course, and divorced him.

Skyrocketing fame and fortune didn’t follow immediately, however. Marilyn got small parts, lost a film contract and eked out a living for some time until catching the favor of 20th Century-Fox’s chairman, Joe Schenck, who hooked her up with a Columbia Pictures contract via the famous, infamous, legendary Harry Cohn. Commencing a pattern that she’d follow for the rest of her life, Marilyn fell emotionally and physically hard for voice-coach Fred Karger – while refusing to submit to Harry Cohn’s notorious aggressive advances.

As much as Marilyn had infatuation-proneness, she evoked the same from countless men. For instance, Joe DiMaggio, who was far from a looker, was understandably crazed with jealousy during their mismatched relationship. And author Arthur Miller, frustrated with his dry, tense marriage, was bowled over by the miracle of such a beauty granting him access to a rare world of carnal wonders, at least for a while. Even her personal psychiatrist, Dr. Ralph Greenson, found her gloomy vulnerability aphrodisiacal. “That thing that she brought out in everyone – I have to save her! – was now far more seductive than her reputation as a sex symbol,” writes Casillo.

And before those men there was William Morris Agency vice president Johnny Hyde, who became smitten with and ditched his entire family in his emotional/desirous delirium. They developed mutual love, but his was much more romantic than hers. Later, when death seemed imminent for him, Hyde proposed marriage repeatedly, which Marilyn refused. “All she could do was offer Hyde her body,” writes Casillo. “He was dumbfounded. His life was filled with meaningless fucks…The more Marilyn said no to marriage, the more he wanted her.” Devastated by Hyde’s death, Marilyn inherited yet another stressor: a “reputation for being a Hollywood whore” and blame for his rapid decline.

Offer her body. For me, that phrase captures Marilyn’s superpower (which I hammer home ad nauseam, I know). And because of this fact, it’s zero wonder to learn through Casillo that she was “determined that her body be showcased in Huston’s The Misfits.” She knew what worked, what was expected – what she wanted to leverage. To take from an earlier Casillo quotation, her body “was her calling card” – but Marilyn also used it as reward, consolation or placation, depending on the circumstance or a particular man’s apparent need. Inevitably Marilyn learned that a wider audience – the world – needed to be rewarded, consoled and placated by her calling card. This need was fed by the now-iconic 1953 Tom Kelley photo shoot of her against a velvet backdrop.

As the “beautiful blonde” she was a hit in John Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle. Then more opportunities came and were fulfilled: Don’t Bother to Knock, O. Henry’s Full House, Monkey Business, How to Marry a Millionaire, The Seven Year Itch, and Picnic. My Lord, anyone bemoaning Marilyn’s deferred dream should consider just that handful of professional accomplishments to dispel undue pity. Marilyn rubbed elbows (and, sometimes, much more) with cinematic giants, and she held her own, for the most part. I think her unreliability and instability are overblown and indicative of either an ignorance or denial of the very typical nature of those shortcomings in countless artists throughout time. Some people’s messes are judged more harshly than others’, I guess.

Despite personal struggles and the fundamental brutality of both the film industry and pop culture, Marilyn continued to land big roles in big movies: Bus Stop, The Prince and the Showgirl, Some Like It Hot, The Misfits and Let’s Make Love. These weren’t chintzy dime-a-dozen Elvis insertions; they were, to different degrees, significant. Yes, she had missteps and duds, and Casillo claims that her passing on the lead role in Breakfast at Tiffany’s “was one of the greatest tragedies of Marilyn’s career,” but I think there’s too much hand-wringing over her real and perceived professional failures and people not taking her seriously. More important, she took herself seriously. Mere poseurs don’t tend to join the Actors Studio to be trained in Stanislavsky’s Method, nor do they become surrogate children to the august likes of Lee and Paula Strasberg and his wife. There’s more to the woman’s craft than Pauline Kael’s attribution of Marilyn’s “wit or crassness or desperation to turn cheesecake into acting – and vice versa” for success.

The more I learn about Arthur Miller and his (undeserved) stroke of fortune in winning Marilyn’s heart and hand (and all the other parts), the more he doesn’t seem to have taken her seriously. Casillo focuses on Miller’s scripting of The Misfits and the squandered chance to compose something much worthier for his wife, “to write a complex and compelling character with Monroe’s qualities.” However, as Casillo notes, her Rosalyn lacked much compelling complexity. As straightforward as Marilyn’s bodiness was, she had real-life drama and trauma to draw from: past molestation, two miscarriages, abuse of prescription pills, suicidal slumps and attempts, emergency and rehabilitative hospitalization, and relatively swift romantic rises and falls.

Eventually fate kicked into high gear when she hooked up with that rake JFK, thanks to her affair with Frank Sinatra, which had led to her familiarity with the Rat Pack and conduit of Peter Lawford, JFK’s brother-in-law. “It was only a lark for him,” C. David Heymann quotes Lawford as saying, “but she really fell for the guy.” A dissertation – nor even a sentence – needs to be rolled out to prove the rapacious sexual gluttony and narcissistic exploitation of the Kennedy men, so suffice it to say that both the White House-ensconced Kennedy brothers knew and used Marilyn Monroe intimately. Though “lark” to the notorious (but lionized) Cad-in-Chief, she had deep feelings and hopes that became wildfire under their betrayal and alienation. And if Lawford is to be believed, “at the height of her anger she allowed how first thing Monday morning she was going to call a press conference and tell the world about the treatment she had suffered at the hands of the Kennedy brothers.” She died that Sunday night.

Casillo doesn’t really get into the suspiciousness running through Marilyn’s last hours, nor very much of the whole slimy Kennedy-brother tag team, but he does point out that “evidence of Marilyn’s relationship with the Kennedys is mostly anecdotal…When we look for tangible evidence of Marilyn’s affairs with the Kennedys – photos, documents, letters – there is little to be found. At least not yet.” And a big reason for this evidence is that “some of it has certainly been destroyed.” At Jackie’s urging, JFK acted swiftly to end the affair and cut off any damning publicity about it, then Bobby pulled away – then Marilyn spiraled into the grave. “Death was certainly on her mind that July,” writes Casillo. “Marilyn very much wanted to change her will.”

Light on conspiracy but not on the ominous, Casillo chronicles the main beats of the infamous last-day story, which should be familiar to even a dabbler of Marilyn Monroe biographies. There’s Marilyn sharing her regret about aging and her fear of a totally lost career with Warren Beatty two days before her death. And then there are her order for a Nembutal refill without Greenson’s knowledge, her suspicion of an affair between Pat Newcomb and Bobby Kennedy, her giving a drunk Peter Lawford foreboding goodbyes on the phone, and Lawford calling for JFK at the White House but not reaching him and eventually going to bed with no further action. Casillo writes that because of this failure to really come through for his friend (and maybe for other reasons) “Lawford was eaten up by guilt feelings over Marilyn for the rest of his life.” Those last days created a perfect whirlpool of soap-operatic, pitiful, inevitable doom – even without the worthwhile conspiratorial questions.

Filmmaker Henry Hathaway said that Marilyn was “always being trampled on by bums.” The scummy Kennedy men were bums, needless to say. Though Frank Sinatra was downright chivalrous (and sexually generous) toward her, he certainly wasn’t an exemplar of fidelity and exclusive commitment. And I think the intolerance for Marilyn’s tardiness, absences and physical failings brought out monstrous hostility in folks who should have known and behaved better. But, really, it’s remarkable how many folks, mostly men, bent over backwards to care for and rescue her repeatedly and sincerely. Arthur Miller, Joe DiMaggio and others deserve some credit. In spite of all the bums and with much help from some concerned guardians, I think Marilyn endured pretty damn well. (While remaining pretty damn pretty, to boot.) Redeeming himself for the silly “something more than sexual” phrase, Elton John sings her transcendence perfectly: “You had the grace to hold yourself/While those around you crawled.”

“Dancing on the Edge of Oblivion”

A common assessment is that Marilyn gradually disintegrated throughout her life, but perhaps that’s not quite correct. There must first be integration for disintegration, and I think it’s safe to guess that Marilyn was never integrated, never in any equilibrium, never in a steady orbit around a definite self which could be nourished properly, let alone allowed to burgeon and deepen. I like to imagine that living to old age would have benefited her rather than gradually destroyed her, as the common prediction goes. In my relatively limited knowledge, I think that more time might have provided space for her to hone her cultural interests, refine her poetry, ripen her life philosophy. I can picture her exclaiming like Margaret Fuller once did: “I feel within myself an immense power, but I cannot bring it out!”

Marilyn Monroe should be remembered and celebrated for her beauty indeed, but, if given the chance, Norma Jeane might have taken center stage of her life again and different kind of respect once beauty’s spotlight dimmed and eventually turned off. “We are too late,” wrote Gloria Steinem. “We cannot know whether we could have helped Norma Jeane Baker or the Marilyn Monroe she became. But we are not too late to do as she asked. At last, we can take her seriously.”

“Sometimes when something is perfect in every detail, it’s not beautiful anymore,” said photographer Bert Stern. “It’s impressive, it’s even slightly intimidating, but you find yourself thinking, ‘Who could possess that?’ Marilyn was possessable.” I doubt that highly. Her possessability must’ve been a mirage. As Charles Casillo writes, Marilyn “is perfected and frozen in time: beautiful, vulnerable, impenetrable, delicious – forever our white goddess.” You can’t possess a goddess, even a perceived/manufactured/hyped-up/illusory goddess, which she wasn’t. Yet Casillo’s following contradiction of her divinity makes so much sense, and it addresses the glorified carnality that I constantly insist should be respected, since she was a sexual genius above all:

Marilyn was not immortal. She was a young woman who was brought up without a moral compass…What she knew was what she had learned out in the world, on the streets of Hollywood, and she used that knowledge for her own survival. Her sexuality was what they valued. Her sexuality was all she thought she had to offer – so sometimes she gave it. How could it be wrong if it gave such pleasure?

Many folks might sum up Marilyn’s ignoble demise as the logical conclusion to burnout and a disillusioned life, but Casillo smartly concludes that “rather than being tired of living, she was tired of dying.” No wonder the thought of Marilyn Monroe seems inexorable from the thought of mortality, and not just because of her actual death. In retrospect it seems as if death loomed over the three and a half decades of her life. “[D]eath was with her everywhere and at all times,” said Arthur Miller, who was far from blind to her precariousness, “dancing on the edge of oblivion as she was.” Consider what she wrote in a poem for a Dr. Mike Fayer:

After one year of analysis…

Help Help

Help

I feel life coming closer

when [all I] want

is to die.

In “Dying Like a Star: Marilyn Monroe’s life and death previewed the opioid epidemic,” featured in the August 2018 issue of American History, Robert Dorfman, Emily Berquist Soule and Sukumar Desai conclude from their analysis that “tabloid stories and conspiracy theories swirled, but one thing was sure: Marilyn was an addict, and addiction killed her, intentional or not.” They tell how Marilyn balanced out barbiturates with amphetamines, how she popped phenobarbital, Amytal, Pentothal and Demerol, and how she overdosed on Nembutal but survived in 1957, thanks to swift action by Arthur Miller. (That close call was a dress rehearsal for what might have been her deliberate or accidental “successful” overdose only five years later.) Marilyn even described herself as “the kind of girl they found dead in a hall bedroom with an empty bottle of sleeping pills in her hands” in an interview with ghostwriter Ben Hecht. One of the main points of the article is that premature death by drug abuse are more commonplace and paid attention to these days: “Now anyone can die like Marilyn.”

The big irony about that statement is that the image of legendary hotties in general tends to have a countervailing effect on gazers, oglers and admirers: a desire for more and more evidence of life, a fear of losing the pleasurable spell, a belief in eternal beauty, at least briefly. As Arthur Miller (who was correct sometimes) said of Marilyn in 1955, “being with her, people want not to die.” She had become a metaphor for miraculous biology, for efflorescent life itself. “Who knows what to think about Marilyn Monroe or about those who turn her sickness to metaphor?” wrote Pauline Kael. “I wish they’d let her die.” (Oh, no, Your Highness Kael! Let her sleep instead! Sleep, so she may awaken again!)

They did let her die. Well, the supposed friends and lovers and professional/self-appointed supervisors of her did back then. But we fans, pop-culturalists and curious biographers certainly keep her alive – and rightly, with all due respect to Ms. Kael. If Citizen Kane teaches us anything, it’s that every individual is an unfinished puzzle, if not a scattered one, and famous puzzles (especially dead ones) puzzle us the most. To riff off of Parker Posey’s line about taking up basket weaving if folks lose sight of hearts’ and souls’ complexity, we are all intricately, sloppily woven baskets (and basket cases). “She attempted to compartmentalize the social part of her life, the therapy part, and the professional part – aiming to be what was expected in each situation,” writes Casillo. “That’s why so many have different ideas of who Marilyn was.”

Marilyn was this, Marilyn was that. Norma Jeane Baker/Mortenson, Marilyn Monroe. Secretly smart, actually stupid. Good actor, poor actor. Star-crossed, full of interrupted promise. There’s no end to speculation, theorization, psychoanalysis, appropriation, exploitation, puzzling. Time and energy can be saved, however, if one steps back so that the separate pieces don’t seem so far apart and, instead, Marilyn is comprehended in the uninterpreted holistic, aesthetic-erotic, Magritte-approvable instant: say, as John Seward Johnson II’s giant Forever Marilyn statue, or in a still of the skirt-blown scene in The Seven Year Itch.

The one most important truth besides the worthiness of the beauty and sexuality of her body is that Marilyn Monroe was far from a failure, far from wasted potential, far from overly fragile and inadequate. She kicked ass, seriously. And because of this conviction of mine, I appreciate Charles Casillo’s Marilyn Monroe: The Private Life of a Public Icon, because it presents the honey without spitting out the bees, but somehow leaves at least this reader with a sense that the honey transcends the stings Marilyn endured as long as she could – and it celebrates her undeniable, radiant, resonant, eternal-instant beauty. Casillo has earned authority in this matter, thanks to his extensive, astute scholarship on the woman.

Both in spite of and because of her beauty, regardless of trampling bums, family insanity, crummy husbands, molesting scum and the fickle fuckery of Hollywood, Marilyn Monroe, because of and beyond the fortunate coalescence of ingenious genes, should be considered a success, not an example of failure for Megan Fox. Perhaps if Marilyn had had a keener ironic sense (or any irony!) she might’ve survived longer. I think of vampy, somnambulant Lana Del Rey, that hybrid of Marilyn Monroe and Jessica Rabbit, whose parodical wit provides a protective existential exoskeleton, and how she, as a beautiful person, seems proud of and unapologetic about erotic feminine power – without pretending that beauty also is immunity from pain and suffering. Take these lyrics from “Beautiful People with Beautiful Problems” from Lust For Life:

We get so tired and we complain

’bout how it’s hard to live…

But we’re just beautiful people with beautiful problems, yeah.

Beautiful problems, God knows we’ve got them,

but we gotta’ try every day and night…

In The Asphalt Jungle, after Marilyn’s Angela character confesses fabrication of an alibi for benefactor Alonzo, she weeps an apology to the jail-bound criminal: “I’m sorry, Uncle Lon. I tried.” Alonzo’s tender reply could be our collective reply to Marilyn herself: “You did pretty well, considering.”

P.S.: By the way, in the tattoo-removal spiel that opened this review it’s obvious that Megan Fox intended her association with Lindsay Lohan as self-righteous denigration. As much as I appreciate the intoxicating Megan Fox (and her darling flat thumbs), I confess belonging proudly to Team LiLo rather than Team MeFo. And quite ironically and blasphemously, I think the January/February 2012 Playboy photoshoot of Lohan in a redo of Tom Kelley’s Marilyn photos surpassed the charming eroticism of the original session (much more than New York Magazine’s prior redo of Bert Stern’s famous Marilyn shoot). Don’t believe me? Check for yourself. Nevertheless, I do understand why Marilyn Monroe remains a dazzling, inspiring, unique miracle to the present day.

Addendum

(This is an excerpt from the 2016 SubtleTea interview about Megan Volpert’s 1976. The full interview can be accessed here.)

David: A fascinating passage in 1976 reveals an unflattering assessment of Marilyn Monroe:

The other day, I found myself embroiled in an argument with my father-in-law concerning the intellectual abilities of Marilyn Monroe. He said she was above average in the smarts department and I said she probably wasn’t. At first, his main warrant for this absurd claim was that we should take a look at her husband because Arthur Miller wouldn’t marry a dummy.

Though I’m a Garbolator rather than a Monroebot, I think both underestimation and overestimation of Marilyn are bad. Sure, Saul Bellow said she “conduct[ed] herself like a philosopher,” but undermining terms such as “childlike sex goddess” (Gloria Steinem), “child-girl” (Norman Mailer), “beautiful child” (Capote) and even “baby whore” (Pauline Kael) have been dominant since her demise. Not that Marilyn was a deferred Atwood or Streep, but I trust Sarah Churchwell when she calls her “a greater Gatsby” and pierces the Dumb Blonde perception: “The biggest myth is that she was dumb. The second is that she was fragile. The third is that she couldn’t act.” Contrarily, you perceptively ask: “[I]f she was the total package and couldn’t maintain, what chance do the rest of us schmucks have?” This happens to echo Steinem on Marilyn: “How dare she be just as vulnerable and unconfident as I felt?” Basically, Marilyn offends you for not taking advantage of her advantage:

So if I give her the benefit of the doubt, I’m trapped with a version of history where a woman who was empowered by both her body and her mind could’ve had all the success of which she dreamed so ambitiously, but instead allowed herself to be subjugated to the position of sex symbol until coping with the emptiness inside herself required so many drugs that she torched her own rise to stardom and died in the weakest way at the least opportune moment…I’d rather believe she was a little too dumb to handle it and she just lost control over her own trajectory. I don’t want to believe that Marilyn Monroe was a picture of the consummate professional, full of intellect and common sense, who nevertheless cracked.

Might both “greater Gatsby” and Dumb Blonde be true? As for Marilyn’s (questionable) suicide, Sexton and Plath also killed themselves, so were they “too dumb” to deal?

Megan: I really like Churchwell’s metatextual projects, and though I ultimately didn’t read most of her book on Marilyn Monroe, the way she went at the subject – the nature of apocrypha itself – was very inspirational to me when I was waist-deep in Warhol research. Monroe died long before I was born, so all I ever have to work with will be under or overestimation, even out of the mouths of people who did actually know her. But I enjoy the second-handedness of most information, the way it mutates over time. We’re left with a kind of Pascal’s wager, where I prefer to gamble that she was sort of dumb so that I don’t live in fear of the implications for myself. Because I’m not dumb.

Nor do I think Plath or Sexton were dumb. I admire Sexton’s work particularly. You might argue that they were rather too smart to deal, not too dumb. That’s a perk of being a writer instead of an actor: you’re writing your own history in your own words. There is a cornucopia of archival material for both writers to convey with constancy and consistency how they felt about life, whereas there is comparatively little material directly out of Monroe’s own mouth, and she is not as articulate as those two writers. The chapter on Monroe doesn’t argue that you’d simply have to be dumb to kill yourself. There are some suicides that I would condone, though they tend to be more in the line of euthanization for physical pain than solely for emotional suffering, for example Hunter Thompson’s suicide.

David: In Making Tracks Debbie Harry said that she “always thought [she] was Marilyn Monroe’s kid.” Even dubbed the “punk Marilyn” (Mick Rock saw more Marilyn than punk), Debbie brought “the whole Hollywood/Marilyn sensibility to [rock],” according to Chris Stein (the Lindsay Buckingham to her Stevie Nicks), and she wanted to be “a mysterious figure that’ll never be able to be truly defined,” echoing Marilyn’s stated desire “to stay just in the fantasy of Everyman.” 1976 presents a fundamental contrast between Marilyn and Debbie: the latter is “in charge of herself” and “campily capitaliz[ing] on her own sex appeal to drive [Blondie’s] image into record sales,” has “actual brains” and excels at puckish duping of fawning males. Later in life Debbie stated the obvious: “Certainly, 50% of my success is based on my looks, maybe more, and that’s a bitter pill to swallow.” Well, duh. As Janet Radcliffe Richards wrote, “Beauty is not a matter of what you are, it is a matter of what you look like.” Might physical beauty be its own sort of genius, as Wilde said? Isn’t love of foxiness more than acumen understandable?

Megan: I’ve wanted to talk about Monroe and Harry side by side since the Warhol book, where I could not find a way to do it to my own satisfaction. So much of that chapter of 1976 is a kind of deleted scene from that other project. In fact, the surplus of thoughts and residual understandings I had during that Warhol project in some sense made 1976 easy pickings among all the other years I could have chosen. It’s no secret that I’m working on a book about Bruce Springsteen right now, and in many ways these books are three of a kind, though they are in no way a proper trilogy.

But you asked me about physical beauty. Warhol, having none himself, sought ceaselessly to collect and then reproduce the foxiness he found in others. Where 1976 openly discusses physical beauty, it’s often as an absence, for example in the chapter on Richard Avedon’s political portraits. I understand that many people think of Springsteen as super hot, but I’m not one of them, and most of those people would likely agree with me anyway that his unusual voice has an ugliness that is the real seat of his rise to celebrity. It’s easy to agree with Wilde because physical beauty on a natural level can be a straightforwardly evolutionary prospect. I also admire people working in fashion, photography, or other arts fields where one is expected to be gorgeous, for the upkeep that maintaining gorgeousness obviously requires – foxiness as a kind of acumen. It’s a skill set, and I do love drag queens. But then eating disorders, expensive cosmetic surgery, and so on. I get through life mainly by displaying acumen, but I’d be foolish and not very feminist to disapprove of Debbie Harry’s good looks or how she used them.

– David Herrle