Rating: ❤❤❤❤❤

“One of Those Great Elemental Barbarians”

Martin Luther wrote what might be the defining statement of his life in 1533: “Almost every night when I wake up, the devil is there and wants to dispute with me…I instantly chase him away with a fart.” All at once these words reveal the man’s off-color wit, which was rivaled only by his intellectual confidence, his despisal of evil, his obsessive penance and his relentless quest for genuine faith.

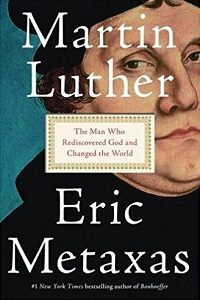

Recently, my deep-down fascination with Luther and the trouble he made (as well as some of the troublesome things he wrote) bubbled to the surface, thanks to Eric Metaxas, author of a new biography, Martin Luther: The Man Who Rediscovered God and Changed the World. Though other biographies of Luther I’ve read are informative and enjoyable, this one excels probably because its author strikes me as having a personal reverence for and special connection to the book’s subject, and some of his own spirituality seems to be more or less inspired by and/or in tune with Luther’s. Fortunately for readers, Metaxas’s sincere respect substantiates and uplifts his prose, without sugarcoating or proselytizing, and they should feel welcomed by the ecumenism and open-doorness Metaxas exhibits. Also, his comfortable tone and fairly subtle theological opining make it no surprise that he is a scholar – and certainly a fan – of C.S. Lewis, that engaging, ever-clever savant of Christian apologia. In fact, Metaxas hosted a forum called Discussing Mere Christianity, which involved Alister McGrath, Douglas Gresham (Lewis’s stepson) and other prominent Christian thinkers.

It’s also no wonder that one of Metaxas’ previous books is Amazing Grace: William Wilberforce and the Heroic Campaign to End Slavery. Due to his heroism as the vanguard of abolitionism and his introspective, reformative Christianity, Wilberforce was at the front of my mind throughout my reading of Martin Luther. In his Real Christianity Wilberforce made Luther-like observations, such as the often concealed contradiction between “outward conduct” and “the true state of the inner person,” the non-Gospelness of assuming righteousness merely “if the good outweighs the bad,” the folly of reducing Christianity “to a set of rules and regulations meant to police behavior,” and so on. “For consciences are taken care of not by laws but by grace alone,” Luther wrote in his monarch-aggravating Against Henry, the King of England, “for by laws, especially human laws, consciences are miserably put out of commission.”

Metaxas presents so much about the two men that parallel and apply to each other: the “unprecedented” nature of their causes, their challenges to the “old way of seeing things” and their world-changing influence. Having boasted that what Wilberforce accomplished “was nothing less than a fundamental and important shift in human consciousness,” he says basically the same about Luther. Wilberforce is “the greatest social reformer in the history of the world,” and he, like Luther, sparked “the greatest revolution in human history.” Against the global norm of slavery, Wilberforce, as Metaxas puts it, endeavored “to tip over something about as large and substantial and deeply rooted as a mountain range.” Truly, the Catholic papacy was nothing less than Luther’s mountain range, and, to recycle praise Metaxas wrote for the much-later English Evangelical, “once his idea was loosed upon the world, the world changed.”

Though associations between the two men can continue indefinitely, we must focus on Martin Luther and consider how much of a big deal – a Big Bang, if you will – his legacy is. Despite his fundamental divergences from Luther, in Saint Thomas Aquinas: “The Dumb Ox” maestro (and Catholic convert) G.K. Chesterton called him “one of those great elemental barbarians, to whom it is indeed given to change the world,” and he recognized that “Luther opened an epoch; and began the modern world.” Likewise, Metaxas aptly sums up Luther as “a genuinely extraordinary human being,” emphasizing, as he does more than a couple times in the book, that

the quintessentially modern idea of the individual…was unthinkable before Luther as is color in a world of black and white…And the more recent ideas of pluralism, religious liberty, and self-government all entered history through the door that Luther opened to the future in which we now live.

Metaxas reminds us that with newly realized individualism came a direct “responsibility before God.” A good analogy for this is a favorite passage from Robert McAfee Brown’s The Spirit of Protestantism. Brown zeroes in on a literal/symbolic architectural change in the Iona Abbey of Scotland, explaining that “in the Middle Ages the clergy sat in the chancel, near the altar, and the laity were confined to the nave. To make sure that no one strayed over the boundaries, there was a screen between the two.” Post-Reformation, however, the screen was removed during remodeling of the abbey. Once figurative and actual screens were removed, the laity were faced with a novel spiritual incumbency.

Here is perhaps the central key to Martin Luther’s revolution or reformation (depending on how you look at it): the belief in the power of and sufficiency of Scripture – with the Gospel as top priority. With access to and understanding of God’s Word, an individual needn’t jump through legalistic hoops, drudge through trivial dicta and worry about, to use pet targets of Luther’s, “feasts and fasts” and “fasts and feasts.” He saw an emphasis on good works that had become a big business for the Church. Thanks to the concept of a “treasury of merit” amassed by Christ, the saints and other exceptional Christians, the popes (in spiritual lineage from foundational Apostle Peter) could grant “indulgences” taken from the holy surplus. What a deal! Now credit for good works could be purchased instead, putting minds at ease – while funding the Church. On top of that, Pope Sixtus IV innovated the idea of buying indulgences for the dead denizens of purgatory.

According to Luther, not only was intentionally profiting from doing what good people should be doing anyway spiritually problematic, but so was the overestimation of good works in the first place. He viewed humankind as sin-laden and utterly fallen from God – essentially dead. So, he reasoned, the works of dead people, even charitable ones, also were dead. “The will cannot hate dead works because the will is evil,” he wrote in The Heidelberg Disputation. “Consequently the will loves dead works, and therefore it loves dead things.” The only way to correct this otherwise insurmountable state, one’s first step must be admission that no help can be achieved outside of God. Luther summed this up with kid-gloveless impact in Confession Concerning Christ’s Supper when he wrote that “we have neither the ability nor the power, neither the intellect nor the capacity, to prepare ourselves to received life and righteousness – or to pursue it.”

As Metaxas shows throughout his biography, Luther was extremely sin-conscious and had an unshakable distrust of the human heart. Instead of self-aggrandizement, he called himself “a miserable and totally unworthy sinner.” Metaxas provides quite a memorable passage about Luther’s laser-like vigilance:

Luther’s overactive mind was constantly finding ways in which he had fallen short, and so every time he went to confession, he confessed all of his sins, as he was supposed to do, but then, knowing that even one unconfessed sin would be enough to drag him down to hell, he racked his brain for more sins and found more.

Immediately my mind goes to Coretta Scott King’s My Life, My Love, My Legacy memoir, in which she admits that her prayerful connection to God also included a spiritual fearfulness: “I was afraid of committing a sin that would condemn me to burn in hell instead of joining God in that mysterious heaven hidden beyond the clouds.” Far from creating negativity or neurosis for her, however, this eschatological sense prepared her to keep up with her husband, Martin Luther King, Jr., who “was constantly examining himself to see if there was any sin that had crept into his life” (and, as Metaxas relates in the lovely introduction, whose father renamed him due to a deep respect for Martin Luther gained during a Baptist summit in Berlin).

Insisting on hours of meticulous confession and seeming like “some kind of unprecedented moral madman on a never-ending treadmill of confession,” as Metaxas puts it, Luther annoyed his confessor, superior, friend and longtime supporter, vicar-general Johannes von Staupitz, who focused more on God’s love than his anger:

Staupitz was an important and busy man, and he didn’t have time for this niggling ridiculousness. Give him a big fat juicy sin, one that anyone could see was a sin, and then repent of it, and be gone! But Luther brought him gnat after gnat, with nary a camel to be seen…He could see that Luther was chasing his own tail, making both of them winded and dizzy.

Luther’s Augustine-influenced drift from Aristotle coincided with the development of his lifelong esteem for direct biblical knowledge during his time at the abbey in Erfurt. He realized the actual low priority the Bible was among monks, who were supposed to be stewards of the Word. Though novices were required to read only the Bible, Bibles were removed from their possession once they graduated to monk status. (I’m reminded of a poignant line in Wilberforce’s ever-pertinent Real Christianity: “The Bible sits dusty on the shelf.”) Metaxas is right on when he observes that “in a world in which we nearly always associate the Bible with churches – and churches with the Bible – it is difficult to imagine a time when the two had almost no connection.”

Disappointing observations and general disillusionment continued after Staupitz convinced Luther to take a trip to Rome, an experience that, as Metaxas speculates, aided him in emerging from the hopeless mire he’d been in. It also opened his eyes to the mire enveloping the papacy. To Luther, many priests seemed incompetent and cynical, and Metaxas notes that “if ever one needed a picture of ‘dead religion’ and ‘dead works,’ here it was in all of its most legalistic ghastliness.” In response to this dearth of sincere faith, he sought to get deeper than legalism and recitation. He wanted divine revelation, anointment, meaning and personal involvement. Of course, the unrest is history.

All’s Well that Ends Will?

Just as there’s only a relative calm in the eye of a hurricane, the sound, fury and significance of a fateful decision, declaration or action aren’t always perceived by the decider, declarer or actor. Not all of history’s giants did this or that with premeditation of fame, and such is the case of the debut of Martin Luther’s renowned Ninety-five Theses, revealed without awareness of the letter’s momentousness. As Metaxas points out, “it was a declaration not to the world…nor even to Rome or to the pope.” Instead, it was intended for fellow theologians and addressed to the attention of Archbishop Albrecht, “so the image in our collective minds of Luther audaciously pounding the truth onto that door for the world and the devil to see is a fiction.”

Metaxas also clarifies that the Theses weren’t intended as defiance or disrespect. Luther didn’t mean to lob a fatal theological grenade into the pope’s lap – but an explosion did result. Among many other key points, Luther declared that guilt can’t be reduced by the pope, canon law is inapplicable to the dead, penalties of sin can’t be evaded by man-alone effort, indulgences aren’t necessary for productive personal contrition, punishments shouldn’t be avoided, the indulgences concept actually undermines the pope’s due reverence, etc. In short, the Theses can be summed up in something Luther wrote in Against Henry: “I seek this one thing only, which is that the divine Scriptures be given the pre-eminence, as is right and just, and that all human inventions and traditions be taken out of the way as most hurtful stumbling blocks.” Also, Mariology and petition to the saints were not biblical, and, for Luther were in fact anti-Christian. Only the spirit of the Gospel, not spiritless legalism, sustained the soul. Laymen could rely on Scripture rather than articles of faith devised by the Church. This is communicated perfectly in a passage from his “Sermon on the Three Kinds of Good Life for the Instruction of Consciences”:

[Blind teachers] think that they are in a right relationship with God, and that they are doing quite well so long as they exercise their office, pray the canonical hours, wear their clerical garb, and do the right thing in church. The laity think the same, that all they have to do is to keep their fasts and feasts. As if our God were bothered in the slightest whether you drink beer or water, whether you eat fish or meat, whether you keep the feasts of fasts!

I associate this notion with a favorite scene in The Pilgrim’s Progress by John Bunyan. Christian is led by the Interpreter into a dusty parlor where a man absurdly tries to sweep away the dust, only to create a choking cloud. At the Interpreter’s order, a damsel sprinkles the room with water, which makes the cleaning easier and productive. Then the Interpreter explains that the parlor represents a man’s Original Sin-tainted heart and the futile sweeper represents the law, while the Gospel is represented by the efficient damsel. Luther saw that God’s house needed sweeping, but he rejected manmade legalism as a viable broom. Metaxas stresses this point dutifully throughout the book, and he always does so with freshness and obvious personal concurrence.

In 1518 Johannes Eck, a prelate of the Church, eagerly sought debate with Luther and rebutted the Theses with an aggressive critique called Obelisks, with which, in Metaxas’s clever wording, “Eck hurled boulders of invective Lutherward.” Unsurprisingly, Luther struck back with a brilliant piece called Asterisks. This rivalry prefigured a larger, much more serious conflict between them a couple years from then.

At the behest of Emperor Maximilian, the Augsburg Diet was arranged to stanch the Lutheran flow. Cardinal Cajetan, who favored Church innovation over scriptural authority, acted as the punitive arm of Leo X, who considered Lutheranism to be “a most pernicious heresy against the Church of God.” Refusing to give in to Cajetan’s prosecution, Luther eventually escaped Augsburg’s wall and fled to Wittenberg after a futile appeal to the pope.

By 1520 Eck delivered Leo X’s papal bull against Luther to Wittenberg. After receiving his copy, Luther threw it into pyre flames, an act which, unsurprisingly, earned him excommunication. “Farewell, thou unhappy, lost, blaspheming Rome,” he wrote. The concrete of the schism had hardened. The notorious excommunicate had achieved celebrity status by the time of the Diet of Worms, so the Church had to also contend with blowback from a majority of smitten Germans. Concluding his refusal to recant, the Diet is where Luther exclaimed his famous oft-quoted words: “Here I stand. God help me. Amen.” Metaxas writes that “if ever there was a moment it can be said that the modern world was born, and where the future itself was born, surely it was in that room on April 18 at Worms.”

Thanks to Metaxas, I was enlightened about a relatively obscured coda to the Diet. A few days later, and more than once, Martin was offered unlikely olive branches by key figures of the prosecution’s side. Perhaps, they thought, there still remained a chance to avert the coming dire tide. This, of course, also failed to soften Luther, so the famous Edict of Worms, which Mataxis likens to an Islamic fatwa, resulted. A fake kidnapping whisked Luther away from arrest and execution so swiftly that sympathizer Albrecht Durer, who wondered if Luther were dead or alive, wrote, “If we lose this man…May God grant his spirit to another…O God, if Luther is dead, who will henceforth explain to use the gospel?”

Absconded to the Wartburg castle in Eisenach, Luther became a “knight” named “Junker George” and lived in seclusion and secrecy, like someone in the Witness Protection Program, for almost a year. There he commenced a German translation of the New Testament, intending to correct errors in previous translations derived from the Latin Vulgate and relying instead on the Greek translation by Erasmus, before a decision to return to Wittenberg and act out in the open once again.

Metaxas’ telling of the famous rift between Luther and the great humanist Erasmus is nothing short of fascinating. Recruited by Adrian VI, the successor pope, to oppose Luther, Erasmus released a book of shrewd criticism: On Free Will. Of course, the prolific Luther fired back with On the Bondage of Free Will, which laid out his anti-free will argument, whose main claim was that humans, as Metaxas puts it, “are under no obligation to do anything at all to save ourselves; indeed we cannot do anything, and it is vitally important that we perfectly understand that we can do nothing. Nothing.”

This is something about Luther that quite irked G.K. Chesterton, who wrote in his book on Aquinas:

Man could say nothing to God, nothing from God, nothing about God, except an almost inarticulate cry for mercy and for the supernatural help of Christ, in a world where all natural things were useless. Reason was useless. Will was useless. Man could not move himself an inch any more than a stone. Man could not trust what was in his head any more than a turnip.

Likewise, in The Well and the Shallows, Chesterton wrote:

It is very difficult to imagine any doctrine that could make man more base, describe human nature as more desperately impotent, blacken the reason and the will of man with a more utterly bottomless and hopeless despair than did the real doctrine of Luther.

By now, Luther had a sense of the infant Reformation’s potency, which gave him the confidence to declare, “In truth, while I live I will be the enemy of the Papacy; if I am burned, I will be twice its enemy.” Of course, almost all things can be related to Star Wars. “You can’t win, Vader,” says Obi-Wan Kenobi in A New Hope. “If you strike me down, I shall become more powerful than you can possibly imagine.” (We needn’t get into the analogy to Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection.)

Touch of Evil

In his response to Henry VIII’s Defence [sic] of the Seven Sacraments, Luther claimed that “all human inventions and traditions” were “most hurtful stumbling blocks,” but if there ever were a moral stumbling block in regard to Martin Luther, it’s his unbelievably reprehensible – and unavoidable – On the Jews and Their Lies from 1543. Nowadays, even folks with cursory knowledge of Luther tend to know of this particular blot, and many condemn him to hellfire for it without a second thought. However, as is usual in many such cases, and in spite of the inexcusable nature of the treatise, the situation is too complex for automatic damnation.

I’m a fan of comic-book writer/artist Dave Sim (of Cerebus the Aardvark fame), and one of my prized possessions is his soul-wrenching Judenhass from 2008. In it Sim chronicles the seeds and fruits of the Holocaust, citing key historical anti-Semitic precursors and continued traditions (though the many anti-Christian tenets of Nazism are omitted). Among the damning quotations, of course, are excerpts from On the Jews and Their Lies.

Up until page 416 of Martin Luther, I’d been waiting and hoping for the author’s take on this nauseating topic, so I breathed a sigh of both relief and apprehension once I arrived to the “Luther and the Jews” chapter. Though Metaxas dedicates only about five pages to it, he does deliver a fairly ample assessment. Thankfully, he provides illustrative context by citing the most important contrasting statement in regard to this topic, from Luther’s “That Jesus Christ Was Born a Jew” from 1523:

If I had been a Jew and had seen such dolts and blockheads govern and teach the Christian faith, I would sooner have become a hog than a Christian. They have dealt with the Jews as if they were dogs rather than human beings…

Right there is the standard by which the later garbage should be judged. The hateful diatribe Luther wrote against the Jewish people twenty years is an evil document entirely, not to mention a major indictment of its author, especially when evaluated from our modern age. However, it must be noted that Luther’s cruel rage was at Jews as perceived stubborn refusers of salvific Christianity rather than as racial enemies, as the Nazis saw them. In fact, it’s this theological/non-racial aspect that highlights the development of Luther’s spiritual hypocrisy and myopic transgression of his own doctrine of the impossibility of humans tapping into God’s concealed will. It seems that he was inflamed by his absolute belief that any vacuum of Christianity served as a garden in which Satanic work could flourish: a spiritual Truman Doctrine, so to speak. Missing the irony that he was once faced with a recant-or-die ultimatum, Luther ended up endorsing a convert-or-die one (as sadistic as any extreme declaration of jihad, if not more so), which is the antithesis of something William Wilberforce stressed in Real Christianity centuries later: “The cure is not forced on us; it is offered to us.”

Metaxas doesn’t get into excerpts from On the Jews and Their Lies, but I think showing some of the highlights here is important: “[O]ne should toss out these lazy rogues by the seat of their pants.” “…so that you and we all can be rid of the unbearable, devilish burden of the Jews.” “…don’t provide them with sustenance and neighborly care…” “What shall we Christians do with this rejected and condemned people, the Jews?” “[D]estroy their synagogues, schools and homes, confiscate their religious works, ban rabbinic activity, withdraw highway protection for them, enslave them and punish them with toil…” “…deal harshly with them, as Moses did in the wilderness, slaying three thousand lest the whole people perish.”

What a far cry from “An Earnest Exhortation for All Christians, Warning Them Against Insurrection and Rebellion,” in which Luther encouraged finesse and avoidance of the urge to “bully or startle” when trying to enlighten folks: “[W]e are to give instruction in our faith with gentleness and in the fear of god to any man who desires or needs it.” He even advised against the futile effort of trying to impart the Gospel to people such as Johannes Eck and his ilk, whom he referred to as “dogs and swine.”

I’m slightly amazed that Metaxas didn’t mention Luther’s “A Meditation on Christ’s Passion,” which identifies sinful humankind in general, not Jews, as the cause of Christ’s suffering:

Some people meditate on Christ’s passion by venting their anger on the Jews. This signing and ranting about wretched Judas satisfies them, for they are in the habit of complaining about other people, of condemning and reproaching their adversaries.

In Katie Luther: First Lady of the Reformation Ruth Tucker writes about Luther’s tendency to fall into “a paroxysm of loathing, a pathological convulsion of rage,” “his inner fury and frenzied demeanor,” “his attacks of dark despair” and his “severe and often acute depression.” I can’t help but consider On the Jews and Their Lies to be a sort of furious and rageful frenzy that has, unfortunately, been immortalized (and ever-mortifying) in history. Curiously, Tucker also addresses the male-chauvinist writings of Luther in regard to wives’ subordination to husbands. “But Luther’s actions always spoke louder than his words,” Tucker writes, “and in his private correspondence with his wife, it is obvious that their marriage was one of mutuality – one of amazing equality for sixteenth-century Germany.” Surely, the sentiments in On the Jews and Their Lies added to the cumulative demonic factors that paved the way to the Shoah – though I highly doubt that the Martin Luther behind those insidious words would’ve supported that pogrom of pogroms.

At the very end of Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil, brothel madam Tanya makes a boiled-down assessment of the paradoxical Captain Hank Quinlan, who possessed both a drive for justice and unethical instincts in his police work before his ignoble demise: “He was some kind of a man.” On one hand this is a perfect way to express the mixture of good and sin in extraordinary people, such as Martin Luther, but on the other hand it can be applied to any person, provided that the time is spent getting to know her or him better. And I think this is how a deep appreciation for Luther can be achieved in spite of the understandably serious repulsion caused by his bizarre anti-Jewish diatribe. Astute studies, such as Metaxas’s book, help us to become more familiar with historical figures and celebrities, thereby also making us worthier judges of their character. If one were to know and judge Luther by only the theological stumbling block of On the Jews and Their Lies, believing him to be an atrocious creep would be understandable indeed, which is ironically similar to Luther’s 1523 comment that “if [he] had been a Jew and had seen such dolts and blockheads govern and teach the Christian faith, [he] would sooner have become a hog than a Christian.”

It’s always jarring and disappointing when respected figures are found to be guilty of reprehensible sentiments, all too human, if not just because such falls from grace should reinforce acknowledgement of our own skeleton-rife closets. For instance, many unsavory aspects of the speech and actions of none other than Gandhi have been questioned. Another example is Muhammad Ali, who is lionized worldwide as a hero, even though in 1975 he told Playboy that any black man who had sex with a white woman deserved execution, and the same was deserved by Muslim women who didn’t date within their religion and race. This is why Churchill Archives director Allen Packwood warned against granting Winston Churchill, a truly remarkable person, “a purely iconic status because that actually takes away from his humanity.” After all, the man was an “incredibly complex, contradictory and larger-than-life human being and he wrestled with these contradictions during his lifetime.” Metaxas says as much when he observes that On the Jews and Their Lies makes us “less inclined to make a hagiographic idol out of Luther.”

As someone who feels road rage almost on a daily basis and finds in it a microcosm of why there has always been and always will be war among humans on Earth, I can relate to failure of temperament, tolerance and self-control. If anyone out there is miraculously unclear on the pendulousness of moods, disciplines, vows, resolutions and righteous aspirations, I refer them to the biblical Psalms, which are more than sufficient in illustrating the radical range of the human heart. In an essay on the Psalms, C.S. Lewis notes that particular ones contain “expressions of a cruelty more vindictive and a self-righteousness more complete than anything in the classics [of antiquity].” “Psalm 100 is as unabashed a hymn of hate as was ever written,” he specifies. “The poet has a detailed programme for his enemy which he hopes God will carry out.”

Embarrassing and damning as it is incendiary and unwarranted, Luther’s anti-Semitic tract is, as Metaxas puts it, “lamentable” and seemingly insensible in light of his previous work. I agree with Metaxas that “these writings force us to ask whether a person’s life can be seen as a whole or must be taken in parts.” I also agree that On the Jews and Their Lies can be seen as a product of the devil’s workshop, which is why I think a better title for it would be The 666 Theses. Though Luther himself never murdered a Jewish person or waged arson against synagogues, the treatise and its sentiments certainly played a part in helping to do the devil’s pogromic work all the way up to the Nazi era and beyond. As Michael Hutchence sings in INXS’ “Devil Inside,” “words are weapons, sharper than knives,” and the Hitlerites’ gleeful adoption and propagandistic exploitation of this unfortunate work shows how true that lyric is. And it’s interesting to further note, as Metaxas has, that “if it hadn’t been for the Nazis, almost no one would ever have heard of these writings.” The sentiments seem to be anomalous rather than characteristic, in other words.

Metaxas also makes the clarifying, though non-mitigating, point that late-in-life Luther also penned the invective-brimming Against the Papacy in Rome, which utterly scorches the pope and not only damns him as Antichrist but dehumanizes him to “werewolf” status. Even years earlier, in Against Henry, he wrote that “the Papacy is the most pestilent abomination of Satan, its leader, that there ever was, or will be, under heaven.” That about takes the cake as far as verifying who the lowest of the low was in Luther’s eyes.

Associating Winston Churchill to Martin Luther once more, regardless of some incidental expression of the ubiquitous anti-Semitism of his time, Churchill also supported Zionism and exhibited respect for Jews, such as when he insisted that “no thoughtful man can doubt the fact that they are beyond all question the most formidable and the most remarkable race which has ever appeared in the world.” Likewise, in 1544, a year after his reprehensible rant, Luther composed a hymn for Judas, whose lyrics contain this far-from-Nazi verse, something I now know of thanks to Eric Metaxas:

T’was our great sins and misdeeds gross

Nailed Jesus, God’s true son, to the Cross.

Thus you, poor Judas, we dare not blame,

Not the band of Jews; ours is the shame.

Gastrointestinal Grace (or Farts and Brimstone)

As a total wreck, I empathize with both Luther’s reportedly blues-caused intense perspiration and lifelong gastrointestinal suffering. Such maladies often are intrinsic to anxious personalities, and Luther certainly had many reasons for mental upheaval – many more than I have. For those out there who struggle with indigestion and such, imagine being famous in history books for having had a horrible bout of constipation. This is what happened to Luther while he lived in seclusion at the Wartburg, and it ended up being a focus of analysis in psychologist’s Erik Erikson’s 1958 book, Young Man Luther, in which he diagnosed Luther as being “compulsively retentive” (something at which Metaxas seems to roll his eyes).

Now imagine for having historical fame for birthing the Ninety-five Theses while going No. 2. Martin Luther’s legendary epiphanic moment certainly is comparable to Saul’s/Paul’s on the road to Damascus, Isaac Newton’s under the apple tree, Siddhartha’s under the Bodhi tree, Arthur’s after extracting Excalibur from the stone, and Moses’s in the holy presence of the Burning Bush – but it’s much closer to Back to the Future’s Doc Brown’s inspiration for the Flux Capacitor after striking his head while falling off a toilet. The Black Cloister’s so-called Cloaca Tower had an outhouse at its base, and it seems that, as Metaxas puts it, the Middle Ages “gave way to the Reformation” while Luther defecated there. Maybe. Probably. Either this was no more than a sarcastic play on words by Luther, or it was an admission that such soaring insight happened from a lowly throne. “The Holy Spirit gave me this art in [or upon] the cloaca,” Luther wrote. Since “cloaca” meant “outhouse” at the time, there’s some ambiguity about whether or not the term referred to the tower itself or the tower’s toilet.

I prefer to believe the latter, mainly because it sharpens Luther’s fundamental doctrine of human fallenness and the absolute need for God’s grace. I associate to Ernest Becker’s The Denial of Death, in which he grimly contemplates defecation’s link to both shame and mortality. “Excreting is the curse that threatens madness because it shows man his abject finitude, his physicalness, the likely unreality of his hopes and dreams,” goes one passage that refers to humans as “gods with anuses.” “But even more immediately, it represents man’s utter bafflement at the sheer non-sense of creation.”

Creation was not non-sense (or nonsense) to Martin Luther, however, and Metaxas illustrates the teleological gravity of humanity’s paradoxical filthiness and godly destiny: “God reached down not halfway to meet us in our vileness but all the way down, to the foul dregs of our broken humanity…In fact, we are not sick and in need of healing. We are dead and in need of resurrecting.” Admission of this low, dependent condition is required for receptivity to divine love, which makes the image of Martin having a spiritual epiphany while (maybe, probably) taking a dump so very apt. “But the shit in its honesty as shit was very golden when compared to the pretense and artifice of Roman gold,” writes Metaxas, “which itself was indeed shit when compared to the infinite worth of God’s grace.”

Really, God bequeathing this “art” while Luther excreted seems to be a potent way to snub the Evil One. It also seems styled similarly to Luther’s comment about farting away the devil over fifteen years later. Instead of Ernest Becker’s “curse” and “bafflement,” realization of the fallen human condition essentially drove Luther to greater existential heights. Here’s how Metaxas describes the momentousness of this golden realization within the “shithole” world:

It is indeed as though every medieval mountain were uprooted and the whole Potemkin range of them cast into the heart of the sea. The hypocrisy of works and human righteousness was forevermore revealed. The curtain was whisked back and the papal Oz exposed as a fraud, frantically pulling his ecclesiastical levers. There would never be any going back.

It would be a shame if the finer aspects of Luther were to be forever neglected due the stumbling block I addressed earlier, for, as Alister McGrath (of the aforementioned Discussing Mere Christianity) wrote in his astute criticism of Cardinal Newman’s Lectures on Justification, he “has an astonishing power to stimulate theological reflection, identifying problems which still perplex today…” If anything, appreciation for his role in challenging monolithic establishments, as well as developing a sort of checks and balances against hubris, is deserved.

I must confess that my former admiration for and study of Luther had been hidden away in storage, so to speak, for many years because of the visceral aversion caused by On the Jews and Their Lies, that miles-high stumbling block. But Eric Metaxas’s Martin Luther provided both a reintroduction and a reevaluation, for which I’m grateful. Writing of his familiarization with William Wilberforce in the epilogue of his Amazing Grace, Metaxas writes, “After months of reading his diaries, journals, and letters I was even sure I knew his voice.” I’m willing to bet that the same thing happened to him while researching Luther. It certainly happened to me, thanks to this splendid book.

Metaxan Prose

Below are some of my favorite passages and lines from Martin Luther. They exemplify the very likable style of the Metaxas’s prose. (Though not included below, I did notice that the author seems to dig the term “marmoreal.”)

Staupitz was an important and busy man, and he didn’t have time for this niggling ridiculousness. Give him a big fat juicy sin, one that anyone could see was a sin, and then repent of it, and be gone! But Luther brought him gnat after gnat, with nary a camel to be seen…He could see that Luther was chasing his own tail, making both of them winded and dizzy.

…to compare any one of the most egregious six popes of that period…to any pope of more recent years is to compare a gorgon to a milkmaid.

…Leo’s habits as a spendthrift made all others look like sober landlubbers.

So only six decades after the invention of movable type, Luther and Eck treated the world to its first typographical battle, waged with pre-Zapf dingbats.

The cardinal and those around him obviously thought Luther some straw-headed hick who had no idea with whom he was fencing…But Martin Luther had not spent the last fifteen years shucking corn.

The technology to print a near infinity of his many writings…made something possible that had never been possible before, to blast a persona…into the wide world, where it would touch the butchers the bakers, and candlestick makers…

Special thanks for William R. Russell’s new translation of some of Luther’s key writings, The Ninety-Five These and Other Writings (Penguin Books, 2017). The book is a welcome and treasured addition to my archives.

– David Herrle