Rating: ❤❤❤❤❤

Back when metal bands such as Iron Maiden ruled the 1980s I was already enamored of punk and alternative rock, wallowing with The Smiths and The Cure, tripping on Dadaist lyrics with R.E.M., and effing it all along with The Exploited, The Dead Milkmen, The Clash, the Buzzcocks, D.R.I, Bad Brains, the semi-divine Ramones, et al. Many of my best pals were Maidenstruck, however, so I was exposed to the band enough to eventually develop genuine respect for it. The Powerslave and Somewhere in Time albums attracted me particularly, and I even smuggled a cassette of the former into my censorious Christian home and hid it under my night table (along with Madonna’s evil True Blue album). Forward to a few years ago, when I discovered Iron Maiden’s Brave New World and Dance of Death albums, from 2000 and 2003 respectively. Then I tried 2010’s The Final Frontier. Absolutely zero deterioration of the band’s early energy (despite personnel changes) – if not more powerful. A Matter of Life and Death and The Book of Souls came next. My fandom’s almost-three-decade-long gestation was complete.

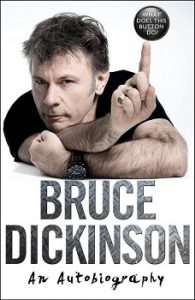

Iron Maiden stands apart from other giants of heavy metal. Much of the band’s subject matter has a literary, even poetic, aphoristic, sutra-like quality. And Bruce’s solo work (his Skunkworks tour de force in particular) is perhaps sublimer in many ways, proving the creative depth of the man behind the front man. As if more proof was needed, Dey Street Books published his new autobiography, What Does This Button Do?, which is a delightful must-read for anyone who appreciates the insights of ultra-interesting people, let alone any serious Maiden/Dickinson fan.

Enlightened and En-Lightened

Bruce is his middle name. He was named Paul at birth. And that’s probably not the only fact that you didn’t know about the man who is Earth-famous for voicing Iron Maiden. Judging by his remarkable eclecticism and creative/productive power, it’s safe to say that Bruce Dickinson is a Renaissance Man. Multitalented folks impress me in general, but I’m extra pleased when the stereotypes of the Shallow Celebrity and the Wastrel Rock Star are contradicted. Several downright scholarly and highbrow famous eclectics/polymaths come to mind: James Franco, Sasha Grey, Eddie Izzard, Paul Robeson, Steve Martin, Sammy Davis Jr., Natalie Portman, Sophie Hunter, Viggo Mortensen, David Byrne, Sonic Youth’s Kim Gordon, Orson Welles, Ben Franklin – heck, Henry VIII.

Besides having a virtuosic vocal range that’s up there with Michael Crawford, Queensryche’s Geoff Tate, Heart’s Ann Wilson, Catherine Wheel’s Rob Dickinson (Bruce’s cousin!) and such, polymathic Bruce has practiced and/or excels at professional fencing, beer brewing, drama, novel writing (The Adventures of Lord Iffy Boatrace, to name one title), film scripting and producing, TV and radio hosting, starting an aviation company and school. He also served in Britain’s Territorial Army and rose through the ranks of the Army Cadet Force. Annnnd – this is the most known unknown thing about Bruce Dickinson – he’s an expert recreational and airline pilot. No, really. Think Fokker Eindecker triplane and Boeing 747s (including Ed Force One, Iron Maiden’s own tour jet), as well as co-piloting flights for British Airways, British World Airlines and Astraeus Airlines.

John Travolta, Harrison Ford and Kurt Russell are just a few celebrities who are serious pilots. More numerous are famous people who’ve died in plane crashes over the decades. Then there’ve been ones who’ve flown to their own (and, even sadder, others’) demises, such as John Denver, John F. Kennedy Jr. and composer James Horner. Undeterred by flight’s crash-prone history, Bruce made his flying debut in a Cessna 152 in 1992. His own words express that day’s momentousness best:

Thus enlightened, my weight was borne heavenwards – or my mass, if you are a Catholic – and, freed of life’s drag by the whirling airscrew boring its way through the air, I thrust my way onwards and onwards. In short, I could fly.

“Enlightened” is a good word to use in regard to both that reverie and What Does This Button Do? in general. Obviously, the intentional or natural play on words, enlightened, is applicable to the basic defiance of gravity required for flight and the holistic disburdening gushed about by enthusiastic pilots, but it also metaphorizes Bruce’s life lessons. Despite the “dark” fame of Iron Maiden, with its ghoulish mascot Eddie and its majority of macabre/occult/Gothic/grim songs, glowing Bruce is scant of pessimism, heaped with hope, abundant with ambition and a soaring creature both literary and figuratively. And the more I learned about the way he thinks and faces existence (and non-existence), the more I noticed the many affirmative, inspiring songs of Iron Maiden and his solo work.

For instance, humanity’s simultaneous glory and doom interpreted through the eyes of an aviator is splendidly expressed in The Book of Souls’ “Empire of the Clouds” song, which involves a steampunk-type airship battle scenario:

She’s the biggest vessel built by man, a giant of the skies

For all you unbelievers, the Titanic fits inside

Drum rolled tight, a canvas skin, silvered in the sun

Never tested with the fury, with a beating yet to come…

Yes, defying gravity is a prerequisite for literal and figurative flight – but so is respect for gravity, even fear of it when appropriate. Without due respect, underestimation or error leads to downfall. Again, this works figuratively as well as literally. Bruce exhibits such respect for gravity: the whatever-it-is that impels everything toward the ground, and the setbacks, emergencies and tragedies (the beatings and the beatings yet to come) in every human life. His successive successes and his phenomenal resilience are based on his reactions to and leverage of those different kinds of gravity. Sure, luck has much to do with goodness and badness in lives, but so does positive defiance and resilience.

In the book Bruce writes that “buoyancy was a family trait” – until him. While his father was an adept swimmer, Bruce “always regarded swimming as thoroughly hazardous.” And here’s what serves as a standard with which to evaluate Dickinson’s drive to rise and refusal to fall: “I am one of nature’s sinkers…Sadly my feet go the way of gravity and the rest follows suit.” A natural sinker, prone to gravity’s pull? A pilot? “No one should go where eagles dare,” goes part of the chorus of the aviation-themed Piece of Mind song “Where Eagles Dare,” a warning that’s echoed in an inverted retelling of myth in “The Flight of Icarus” later on the album. Bruce essentially replies, “Says who?”

While practicing and perfecting his fencing under Hungarian coach Zsolt Vadaszffy, Bruce learned to stare down chance and error. The word “enlightenment” occurs again:

At some point in the evolution of the relationship between master and pupil, enlightenment occurs. I mean this literally. It is as if a chain has snapped, and your body and mind have been freed of intention – freed of the tyranny of “What if?” and the consequent fear of failure.

This must-do attitude is most important in how Bruce dealt with being diagnosed with HPV-caused cancer of the head and neck in 2015. Besides being horrifying news that would topple just about anyone, the location of the discovered tumor could have been the total end of the singer’s career, if not the end of his very life. “For three days or so, all I noticed were hospitals, churches and graveyards,” Bruce writes of the initial blow. “By God, London was infested with the bloody things.” Not surprisingly, he didn’t succumb to denial or despair. He faced the tribulation like a pilot rather than a passenger. He…respected the gravity while defying it. “Be afraid and be scared,” he writes about flight perils elsewhere in the book, “but panic will kill you, not fear.” My mind goes to some lyrics from “The Wicker Man” on Brave New World: “Hand of fate is moving and the finger points to you/He knocks you to your feet and so what are you gonna do?”

Bruce endured radiation and chemical therapy (cisplatin), along with all the nasty inevitable side-effects and suffering. In spite of loss of hair, taste and appetite, he kept relatively busy (whereas I’d be a glum, fallow puddle) and lived against death’s gravity with the lift and thrust needed to stay afloat. Though the seriousness of the situation is certainly expressed in the narrative, Bruce doesn’t withhold the ironic humor that is consistently strong throughout the autobiography: “The ‘platin’ bit of cisplatin refers to platinum, which I was shoveling into my cells. I had plenty of platinum albums and now I was turning into one.”

Really, I could stretch the hell out of this analogous conflation of cancer survival and piloting – so I will. The other death-defying episode in Bruce’s life is when his plane malfunctioned and was rapidly losing altitude, leaving him with a mere couple minutes before impact. This mere couple of sentences can be used to describe both his resistance against panic and his bravery during cancer treatment: “I forced myself to grip my terror, and I squeezed it really, really hard. I had my fear by the throat in one hand, and with the other I thought to crash the aircraft somewhere survivable, so I’d better start looking below.” Of course, with much pluck, luck and a lot of holy fuck, he escaped the ultimate consequence of gravity. “I landed in Vegas and bought an omelette and chips,” he writes, showing the casual coolness of a, say, Steve McQueen, another eclectic and daring man (racing, stunts, piloting) who, sadly, wasn’t so lucky with his cancer.

“Say goodbye to gravity and say goodbye to death,” the “Wicker Man” lyrics continues. “Hello to eternity and live for every breath.”

“NON-SINGER”

Believe it or not, one of the finest voices in history once failed a singing test for the school choir. A teacher’s note reads: “Dickinson – Sidney House, NON-SINGER.” (The publishers who passed on Agatha Christie were just as a foolish.) Destiny disagreed, and Bruce became a vocal master. In a chapter called Organ Pipes, he spends about three and a half pages spieling on proper breathing, lung capacity, the diaphragm, etc. Among many other things, I learned that optimal voice preservation requires “loads of sleep in a quiet room with no air-conditioning, just an even temperature and good humidity.” (Sounds like an effing nightmare to me.)

Bruce’s seminal inspiration to pursue a career in music was hearing Deep Purple’s “Speed King” while a student at Sidney House: “I had memorised [sic] Deep Purple’s Made In Japan note for note…Ditto the first Black Sabbath album, Aqualung by Jethro Tull…” Discarding his original wish to be a drummer on par with Keith Moon, he filled in as vocalist for a band called Paradox, sang for another band called Speed, and then helped form a band called Shots. “We called ourselves Shots, but we could have called ourselves Anal Catastrophe and only had to change one letter,” he writes. “It was the era of punk, after all. I thought it was a rubbish name as well, but I couldn’t think of a batter one.” By 1979, Bruce was in a band called Samson.

Luckily, through producer Martin Birch, he was eventually steered toward Iron Maiden, who had already put out the successful Killers album. “This was a modern-day Deep Purple, but with a theatrical side…,” Bruce remembers. “Darth Vader didn’t stand there hissing and clanking saying, ‘It is your destiny.’ He did not have to. They had Eddie.” Eddie, the creepy corpse-like creature featured on every album cover, seems less of a shocking monster and more of a manifestation of existential/spiritual turmoil, or perhaps a living mirror of our repressed rage, our berserker basis, our Thanatotic tendency. While Bruce is the truly unique voice of Iron Maiden, Eddie is its snarling face. One of my favorite passages in the book is Bruce’s assessment of Eddie: “Eddie is Iron Maiden’s mascot, monster, alter ego – call it what you will. Part supernatural, part animal, part aggressive adolescent, Eddie is a super anti-hero with no backstory. Eddie doesn’t give a fuck. He just is.” Wow. “Aggressive adolescent,” “no backstory?” I’d never thought of Eddie that way, but now I can’t think of him otherwise.

Feeling destined to be Iron Maiden’s lead vocalist, Bruce auditioned and succeeded (surprise, surprise). From then on the band had perfect lift and thrust for a flight to fame. Luck also has much to do with it, for, as Bruce writes, “the interpersonal chemistry required to sustain a global rock group over many decades is nothing short of a miracle…The temperature of the porridge has got to be just right.”

As far as I’m concerned, Iron Maiden’s miraculousness peaked by the Piece of Mind album, when the band was comprised of Bruce Dickinson, bassist Steve Harris, guitarists Adrian Smith and Dave Murray, and drummer Nicko McBrain. Bruce observes that “it is the third album that determines whether it is the end of the beginning, or the beginning of the end for a band or artist;” the fact of the success of The Number of the Beast, the third Iron Maiden album and the first one starring Bruce, supports this.

An excellent lyricist himself, Bruce describes the genius of bassist/primary songwriter Steve Harris: “For [him], the words exist in rhythmic space first and foremost, then perhaps lyrical or poetic space, and lastly a format designed to make the most of the human voice.” He also praises Nicko McBrain, “a dead ringer for Animal from the Muppets,” as an “overqualified” drummer, and marvels at “the musical Tourette’s that comprises the McBrain damage.” Come on, people. Any band whose drummer’s last name is McBrain is destined for greatness.

Ace

Bruce is a wonderful writer, and What Does This Button Do? is just another effing enviable achievement of the relentless trooper. Whether it’s dropping names such as Gary Larson (of The Far Side fame), William Blake, Yukio Mishima, Bruce Lee, Proust, Henry Miller – and Hannibal Lecter, or jabbing with a nice pun or wisecrack, his prose contains much wisdom, wit and, dare I say, gravity. Below are several favorite lines from the book:

My Falstaff days were long gone.

We despised fashion, hated the cult of celebrity and thought the concept of “all you can eat” as disgusting as its obese participants.

[T]he Boeing 747 is a beautiful brute…Think of it as half the power of a jumbo jet strapped to a quarter of the weight. A lightweight 757 is climbing off the runway with a vertical speed of 60 miles an hour – in excess of 6,000-feet-per-minute ratio of climb.

There is no more lethal way to dispense with a human being, other than a firearm, than by running them through with a sword.

…I began to look at girls in a different light…[T]here was something more that you could diddle about with. I just couldn’t put my finger on it.

It was masturbation and libraries that saved my soul from the nervous-minded proselytising [sic] and a stifling, evangelical straitjacket, and thank God for that.

Genocide is going on right now somewhere in the world, but it is the innocent plight of a child about to die that cuts to the very soul…

…the nun-devouring son of Satan, the cardinal of carnality, the great and powerful Blackie Lawless…

No birds fly over Auschwitz. It is as if the very soil contaminates the air with the stench of death and the evil of those who walked upon it and planned the horror. It is the banality of industrial-execution planning contrasted with the screams of the gas chambers that is the true measure of the terror. That terror, I believe, is the secret fear that we may all be such monsters deep down. It makes me shudder to even think of it.

The germ of a philosophy started to take root. The idea that it didn’t matter what it was that you engaged in, as long as you respected its nature and attempted some measure of harmony with the universe.

I’d be remiss in beating the dead metaphor if I didn’t include lyrics from Powerslave’s “Aces High,” which sum up the ambitious, survivalist, skyward nature of Bruce Dickinson:

Rolling, turning, diving

Rolling, turning, diving, going in again

Run, live to fly, fly to live, do or die

Run, live to fly, fly to live…

– David Herrle