Rating: ❤❤❤❤❤

I hid myself within myself…and quietly wrote down all my joys, sorrows, and contempt in my diary.

– Anne Frank

“But this isn’t like other comics…It was so…so personal!”

– Mala, Maus

Anne X

There’s not a drop of intended hyperbole in the introductory claim I’m about to make, so gird yourselves. The diary entries of short-lived teenager Anne Frank are more profound and nuanced, and wiser and worthier, than all of the writings and utterances of the Nazis, their true-believing antecedents and adherents – and even every pretentious humanist or humanitarian, combined. The final entry in the diary, written on August 1, 1944, which concludes with the famous “if only there were no other people in the world” phrase after much poetic, virtuosic self-analysis, is a tour de force in itself. “Precocious” is a weak term for Anne and her musings that are pendulously naïve and incisive, green and gray, pitiable and enviable. Rereading her complete diary after many years has reinforced my awe for this unlikely icon and a shame for my emotional/moral weakness in the face of comparatively trivial trials. Few – if any – of us can stand proudly before towering Anne Frank and feel as noble, let alone as brave. She’s been idealized and semi-deified, yes, but the proof of her deserved greatness is plainly on record for anyone to discover and admit.

Autobiographies are commonly credited as the result of the confessional tendency in humankind, and they also are discredited as things of unavoidable falsehood, embellishment and skewed recollection, showboating exercises of self-centeredness. Many of them seem fairly straightforward and as objective as possible, while others seem proudly at liberty: more literary art than accurate chronicle. (My mind goes to, say, Klaus Kinski’s Kinski Uncut, Casanova’s The Story of My Life Until 1787, Rousseau’s Confessions and Chuck Barris’ Confessions of a Dangerous Mind.) This goes for published diaries as well. Such writing is often fundamentally done with future readers prominently in mind, or merely naturally prideful enough to cause automatic self-editing and persona-weaving.

But, I have to say, this doesn’t seem to be true of “Kitty,” as Anne Frank named her diary, which she said had qualities of “a book of memoirs.” Judging by her own words, one senses that Anne didn’t design it for public – let alone popular – posterity, and that the pages were filled by a person who truly wrote from therapeutic compulsion, overflowing emotions and an energetic but frustrated imagination. Whenever I read the diary I think: This is Anne, unfiltered, free of pretense, what we see and what we get. And if this is indeed the case, I can’t imagine Anne with filters and pretense, with ironic performance for future audiences.

If there ever were a laughable quality in Anne Frank it’d be her desire for equilibrium. On January 30, 1943 she wrote: “It is impossible for me to be all sugar one day and spit venom the next. I’d rather choose the golden mean (which is not so golden), keep my thoughts to myself…” Oh, that’s cute, but lukewarm moderation was certainly not her domain. Instead, she embodied the biblical Psalms and was every bit as moody: ecstatic and despaired, mirthful, bitter, grateful, irate.

“I can shake off everything if I write,” wrote Anne, “my sorrows disappear, my courage is reborn.” Her entire diary is filled with alternating tides of sorrow and courage happening in the cramped hiding place at the back of Otto Frank’s business building, a refuge the fugitive residents called the Secret Annex. It presents an unvarnished individual in a full spectrum of human emotions, communicating seemingly effortlessly but under burdensome weight. And the positive/negative honesty from frank Anne impacts us at point-blank range. Some examples of her Psalmic fluctuation follow:

Kitty, if you only knew how I sometimes boil under so many gibes and jeers. And I don’t know how long I shall be able to stifle my rage. I shall just blow up one day.

No one is spared – old people, babies, expectant mothers, the sick – each and all join in the march of death.

Jews and Christians wait, the whole earth waits; and there are many who wait for death.

Who has inflicted this upon is? Who has made the Jews different from other people? Who has allowed us to suffer so terribly up till now?

Why do I always dream and think of the most terrible things – my fear makes me want to scream out loud sometimes. Because still, in spite of everything, I have not enough faith in God.

I swallow Valerian pills every day against worry and depression, but it doesn’t prevent me from being even more miserable the next day…I feel afraid sometimes that from having to be so serious I’ll grow a long face and my mouth will droop at the corners.

I do talk about “after the war,” but it’s as if I were talking about a castle in the air, something that can never come true.

[I]n time this gloom will wear off.

Now I am getting really hopeful, now things are going well at last. Yes, really, they’re going well!

I’m blessed with many things: happiness, a cheerful disposition and strength. Every day I feel myself maturing, I feel liberation drawing near, I feel the beauty of nature and the goodness of the people around me. Every day I think what a fascinating and amusing adventure this is! With all that, why should I despair?

It is God that made us what we are, but it will be God, too, who will raise us up again.

[A] person who has courage and faith will never die in misery!

In this excerpt from August 1, 1944 Anne is boiled down perfectly:

I’ve already told you before that I have, as it were, a dual personality. One half embodies my exuberant cheerfulness, making fun of everything, my high-spiritedness, and above all, the way I take everything lightly…This side is usually lying in wait and pushes away with the other, which is much better, deeper and purer. You must realize that no one knows Anne’s better side and that’s why most people find me so insufferable.

Anne belongs in a special pantheon of transcendent individuals whom I call doomsingers, folks who are capable of keeping their heads out of the sand of denial without splitting apart in misfortune’s squall. They stride upright through infernos and muster smiles in bloodbaths. Doomsinger Anne puts it best: “I have to laugh at the humorous side of the most dangerous moments.” Perhaps it’s her authenticity (a term I hesitate to use, given its sociopolitical overuse these days) that makes such statements from her so credible, in contrast to eyeroll-worthy/ feel-good/Norman Vincent Peale/positivity-fanatical pretenders. “I have an odd way of sometimes, as it were, being able to see myself through someone else’s eyes,” she wrote in January 1944. And later that month she wrote: “I have one outstanding trait in my character…and that is knowledge of myself. I can watch myself and my actions, just like an outsider.”

Longing to become a great journalist and author, Anne acknowledged her diary’s importance for those hoped-for eventualities, though it’s doubtful that she believed that the diary would be the sole vehicle: “Whether I shall succeed or not, I cannot say, but my diary will be a great help.” Thanks mostly to benefactor Miep Gies and her father Otto Frank, who preserved and prepared the diary for publication, the latter goal was achieved, albeit it posthumously. She didn’t think that anyone would “be interested in the unbosomings of a thirteen-year-old schoolgirl,” unaware of the diary’s destiny and the eventual interest of millions of readers. Through the diary she meant “to bring out all kinds of things that lie buried deep in my heart,” and she left words that can never be buried. Or, if you prefer, each reading of the diary is a sort of spiritual resurrection.

Anne believed that she was “living through a big adventure” which motivated her to sustain her singular personality while entrapped in close proximity to “a hypercritical family in hiding,” essentially sentenced to stressful, strategic silence and deprivation in the Secret Annex for over two years, relying on the stealth of selfless Dutch friends and the subterfuge of a door-concealing bookshelf, Anne shouldered a burden that would break the majority of the best of us.

Anne is now a titanic historical hero, essentially a sage-/saint-like figure who found enlightenment in the Secret Annex rather than under a Bodhi tree or at Mecca, a martyr for the spirit of love who could have boomed with mass-moving prophetic rhetoric had she the chance. But also a total badass next to the dinky likes of the devils who destroyed her, a ripe subject for an audacious Quentin Tarantino alternate history in which Anne arms up, figuratively and literally, and humiliates Hitler before executing him on the Nuremberg stage. Call it The Autobiography of Anne X!

“A Patch of Blue Sky Surrounded by Menacing Black Clouds”

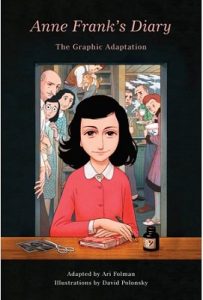

Really, all words are too small to properly honor the magnitude of Anne’s words, but combining the right images combined with them is particularly conducive, as proven by Anne Frank’s Diary: The Graphic Adaptation by author Ari Folman and illustrator David Polonsky. Their partnership has produced a very worthy comic-book version of the world’s most famous diary – and it works. I believe wholeheartedly that Anne would approve of her soul bared in this medium. And I can fantasize the diary entry: “Dear Kitty, two kind gentlemen made our story into a comic book! Oh, how wonderful!”

Art Spiegelman, most famous for his game-changing autobiographical comic series Maus, explained comics’ peculiar power to Claudia Dreifus for The New York Review of Books in April 2018: “In my line of work, one is always hunting for that essentialization. Comics do that especially well. They permit you to boil down an image and a thought to its essence, with the two circuits mixing the words and images.” In The Graphic Adaptation Folman and Polonsky have mixed words and images to essentialize what seems to be unessentializable. (Anne was an essence of one, essentially.) The book features carefully selected excerpts and some complete entries from the text of The Diary of a Young Girl, the Definitive Edition (1995), with images that never fail to provide emphasis, visceral symbolism and conceptual abstraction that only comics can.

There are some worthy comics that deal with the genocide against Jews, such as Bernie Krigstein’s 1955 EC comic, “The Master Race,” and, more recently, Grek Pak’s and Carmine Di Giandomenico’s X Men: The Magneto Testament. But perhaps the most incisive one is Judenhass by Dave Sim, who is most famous for his long-running Cerebus the Aardvark series. Sim felt compelled to illustrate and write a graphic chronicle of the endless tradition of worldwide Jew-hatred (what the term judenhass translates to), highlighting the seeds and fruits of the Shoah and citing key historical anti-Semitic precursors and continued traditions (though the many anti-Christian tenets of Nazism are omitted). In the opening text of the book he reveals his belief that

every creative person should consider doing a work addressing the Shoah…at some point in his or her life. And it seems to me this is nowhere truer than here in the comic-book field which was created, developed and built primarily by Jews…

In the Adapter’s Note of The Graphic Adaptation, Ari Folman admits that “the idea of the graphic adaptation gave me pause,” but he dared to go ahead with the project anyway. “We did…try to visually interpret and preserve her powerful sense of humor,” he wrote, “her sarcasm…, and her obsessive preoccupation with food…” It can’t have been easy to decide on what to include and what to omit, but most of what is shared is integral to the intertwined Secret Annex/Anne story. The book is quite remarkable in how it consolidates so much information and preserves the heaviness of the subject while taking its intermittent lightness to comedic levels. I plan on using this adaptation when it’s time to introduce my children to Anne Frank, before the actual diary.

Right away Polonsky’s impressive talent for rendering likenesses of real people is displayed on an introductory character-cast page: Anne, her sister Margot, her father Otto (whom she affectionately called “Pim”), her mother Edith, Mrs. Petronella van Daan (Auguste van Pels), Mr. Hermann van Daan (Hermann van Pels) and their son Peter, dentist Albert Dussel (Fritz Pfeffer), and main benefactors Johannes Kleiman, Victor Kugler, Bep and Johan Voskuijl, and Miep and Jan Gies. (It’s worth comparing the portraits with actual photos.) Fantastic, surreal, even slapsticky images appear throughout the book, revealing the comic within the tragic, and exercising artistic license without dishonoring or cheapening the source.

The Graphic Adaptation covers the highlights of Anne’s pre-Annex days, before almost all activity from then on is shown taking place in the not-so-spacious hideaway. After Jewish status becomes untenable in public life, Kleiman and Kugler take over running Otto’s company, and the Franks go into hiding after staging a hasty flight to Switzerland to throw off the Nazis. From then on, “like being in holiday in some strange hotel,” as Anne puts it, they are confined to the Secret Annex, which is conveniently presented to readers in a cross-section illustration by Polonsky.

The van Daans were invited to hide at the Annex as well, so Polonsky captures Anne’s critical, witty assessment of each person amusingly in little fictional vignettes. For instance, while bombs drop Mrs. van Daan, with her coat and dress hiked up, says, “If I must die here, I might as well be sitting on my chamber pot.” The prized possessions of the van Daan couple were, ironically, a chamber pot and a teapot (what goes in must come out, after all), and the chamber-pot gag recurs several times throughout the book without getting old.

Humorous imagery is used again on a page showing the contrast between the sisters Anne and Margot. Via Polonsky’s visual shorthand one gets that Margot is usually serene, self-controlled, a reader rather than a frantic writer, neat and orderly, passively upset rather than aggressive, prone to laughter rather than sobbing, accepting the meager food dutifully rather than broadcasting her disgust, garnering approval from all instead of storming from the room into solitude. Needless to say, Anne is not usually those things, and, as she spitefully puts it, her older sister is “the cleverest, the kindest, the prettiest, the best!!!” Anne’s fixation on who she is, how she behaves, how others perceive her, and who she wants to become is expressed in many fantastical frames. Perhaps the most amusing imaginary scenes are a couple of full page depictions of Anne as the subject in two famous paintings: Munch’s The Scream and the portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer by Klimt, as well as her reading Cinema & Theater magazine while imagining herself as different actresses of the time: Bette Davis, Joan Fontaine, Carole Lombard, Katherine Hepburn, Ingrid Bergman and Marlene Dietrich.

The illustrations are particularly good at communicating Anne’s constant complaints about the other residents, including her parents (mostly “Mummy”). For instance, bordering an entire entry on all four sides are bickering Mr. and Mrs. van Daan and Edith Frank as flame-spitting dragons. In another part, a bizarre two-page spread shows everyone seated around the dining table, with animal features instead of human ones: Daddy as an ostrich or some other kind of bird, Anne as a bird, Mummy as a sheep, Margot as an owl, Mr. van Daan as gluttonous bear, Mrs. van Daan as a prim rabbit, Peter as a cat and Dussel as a wolf or dog. As an example of how silly but darkly contextual the fictional stuff can get, in a series of versatile ways to use various tiresome foods, someone engaging in “meatloaf art” forms Hitler’s face.

The book also plays around with the rather funny fact that the residents had such a massive supply of beans, which not only eventually nauseated them but compelled Anne to write of beans, beans and more beans in her entries. Polonsky drew Peter spilling a sack of them and the resulting tedious, meticulous cleanup that went on for days. There’s also a frame showing a ridiculous number of sacks covering the van Daan’s living area, with Mrs. van Daan asking (from her chamber pot, of course): “Do you know how much gas one person can produce from 300 pounds of beans?” I don’t recall a line like this appearing in the actual diary, but it sets up another visual joke of lots of people from many different nationalities holding their noses while filling the air with brown clouds of mass flatulence. Folman fabricates more comedic lines: “And now it’s BBA – Brown Beans April. Beans in my body, in my mind, in my soul…Imagine the entire world fueled by beans…” Digestive gas is mentioned at least a few times in the diary, mainly in a mirthful February 1943 passage about Peter and a cute misnomer (which I wish had been included in the book):

One afternoon we couldn’t use the toilet because there were visitors in the office. Unable to wait, he went to the bathroom but didn’t flush the toilet. To warn us of the unpleasant odor, he tacked a sign to the bathroom door: “RSVP – gas!” Of course, he meant “Danger – gas!” but he thought “RSVP” looked more elegant. He didn’t have the faintest idea that it meant “please reply.”

Polonsky also masterfully visualizes Anne’s anxiety and dread, particularly in regard to the terrifying bombings during which she’d snuggle in bed with her father. Negative episodes in general are depicted effectively. It pleased me to see that The Graphic Adaptation includes some scenes about a Mr. W.G. van Maaren, a creepy guy who worked in the warehouse of Otto’s business. It’s almost certain that he blew the whistle on the Annex dwellers and set the arrests into motion. “He is suspicious,” writes Anne, “he asks too many questions, he’s no fool, and he is cruel.” In The Diary of Anne Frank: The Critical Edition Harry Paape points out that van Maaren’s suspicion about hidden Jews was so strong that some evenings he “would set small traps in the warehouse…To the protectors, this seemed to indicate that he suspected someone was hiding in the building and was trying to make sure.”

Yes, all words are too small to do Anne’s magnificent words justice, and, likewise, the claustrophobic Secret Annex was a teapot containing a tempest, while the chamber-pot world outside filled more and more with shit. I also was pleased that a long excerpt about Anne’s sense of being under siege was included in full, set against an image of the residents standing on a white cloud above a burning, smoky hell, beneath an opening of bright, glorious light:

I see the eight of us in the Annex as if we were a patch of blue sky surrounded by menacing black clouds. The perfectly round spot on which we’re standing is still safe, but the clouds are moving in on us…We’re surrounded by darkness and danger, and in our desperate search for a way out we keep bumping into each other. We look at the fighting down below and the peace and beauty up above. In the meantime, we’ve been cut off by the dark mass of clouds, so that we can go neither up nor down. It looms before us like an impenetrable wall, trying to crush us, but not yet able to. I can only cry out and implore, “Oh, ring, ring, open wide and let us out!”

Grim Interlude: Judenhass

The Shoah is a unique historical event. Though there have been and will continue to be numerous mass atrocities (mini-holocausts, if you will), the methodical, weaponized-technological high-scale murder of primarily Jewish people masterminded by the Third Reich stands as a measure for all other sadistic, thanatotic scourges. As Dr. Fredric Wertham put it, “the administrative mass killings of the Nazi era constitute something new in the rich history of human violence.” And Mathias Freese, author of The i Tetralogy and I Truly Lament: Working Through the Holocaust considers the Shoah to be “the single most important human event in world history.”

Hitler’s rhetoric against Jewry didn’t pop from a vacuum and suddenly seem sensible to the masses. Early Europe served as the bedrock for anti-Semitism, a fact that prompted G.K. Chesterton to call the Jews “the most famous scapegoat in European history.” “It is not too abnormal an activity for any Europeans,” wrote Ben Hecht in Perfidy (1961). “It has gone on for centuries, the tom-toms beating a hate for Jews.” Jew-hatred stemmed from the ancient cycle turned by the oppressive Pharoahs, then among the Visigoths, through the collective grudges and fears of post-barbarian Europe, the military and conversion glory of Charlemagne (one of Hitler’s models), the pogroms and exiles and fluctuating tolerance and clampdowns, the antisemitism of the Enlightenment (Volatire, etc.), the Dreyfus Affair, etc. Though Muslim Spain was a richly cultured and cooperative time for Jews, it was relatively short-lived. When the first Crusades started in 1096, there was repercussive action against Jewish “infidels,” particularly in Germany. An army terrorized the Jewish areas of the Rhine district; Jews were slaughtered in Worms, Cologne, and many other cities until Henry IV tempered the bloodthirst and took measures to protect Jews.

Of course, atrocities flared up again, despite Bernard of Clairvaux’s imploration against such mistreatment and madness. Toledo Jews were mobbed in 1212; the Fourth Lateran Council included the canon that prohibited Jews from gaining office, hiring Christian servants, and from public appearance during Easter. Murders were conveniently blamed on Jews (as blood collection for Passover observance), vengeance was generally dealt by mobs and raids. Despite his celebrated points, Martin Luther’s violent invectives against “vermin” Jews enflamed later, religious rationalizations against the people. (Such venom contradicted Luther’s sympathetic “That Jesus Christ Was Born a Jew” (1523), in which he “would sooner have become a hog than a Christian” if he’d been a Jew witnessing the behavior of many Christian “blockheads,” as well as blaming those same Christians for treating “the Jews as if they were dogs rather than human beings.”) And let’s not forget Hitler’s musical and racial mentor: Richard Wagner, the talented Jew hater complete with belief in a conquering Aryan Jesus.

Really, judenhass is a global, memetic plague. In “What is a Jew?” James Baldwin observed that the Jews “are united by the evil that is in the world, that evil which has victimized them so savagely and so long.” Likewise, Ben Hecht noted in A Guide for the Bedeviled that the anti-Semite “can climb out of his sense of inferiority by bashing Jews – and, at the same time, line up with the great of history.” Jews’ fundamental crime in the eyes of their annihilators has been their existence itself rather than tribe, territory, political power and such. They weren’t even worth anything as slaves, as far as the Nazis were concerned.

In April of 1944 Anne mused over the existential persecution of Jews and wondered about God’s plan in the wake of it all. The following excerpt exemplifies her sense of Jewish destiny and a salvational aspect of her people’s agony:

If we bear all this suffering and if there are still Jews left, when it is over, then Jews, instead of being doomed, will be held up as an example. Who knows, it might even be our religion from which the world and all peoples learn good, and for that reason only do we have to suffer now…

“Mother, Do You Think They’ll Like This Song?”

The handwritten material that would become the famous diary was found locked up in Miep Gies’ desk. Thankfully, it had been retrieved from the Secret Annex and spared destruction by the police. Otto, honoring his daughter’s earnest dream of publishing a book someday, typed up the writings and eventually got them published. Sickeningly enough, there were aggressive accusations that the diary was a forgery, some leading to legal conflicts, but serious testing led to vindication of the diary’s provenance via a 250+-page report by The State Forensic Laboratory. Writing supplies, document examination and handwriting identification were rigorously examined with the employment of infrared spectrometry, fiber analysis, X-ray fluorescence and chemical analysis. As H.J.J. Hardy wrote, “none of the tests produced any indication that the diaries, the loose sheets and the items submitted for comparison, together with the ink deposits found in them, are of later date than the supposed period of origin.” He also noted that the writing itself could be attributed to Anne – “bordering on certainty.”

The mere 26 corrections not done by Anne were done by Otto. Also, as Harry Paape put it, Otto initially “omitted whatever he felt would prove of no interest to [relatives and friends], together with passages that might offend living persons, or remarks about Anne’s mother that ‘didn’t concern anyone else.’” Though he did leave in a lot of relatively controversial stuff, he later admitted omissions of “entries by my daughter which it was felt might cause offense to the reader.” Anne herself wrote in one entry: “I hope Mother will never read this or anything else I’ve written.”

Reading the full text of the diary is a must, however, and the fact of the dire rift between Anne and Edith should neither be ignored nor lessened. Noting that Anne felt constantly embattled with her mother, whom she called “this insensitive person, this mocking creature,” is an understatement. To really hit home in regard to this, Folman put a lot of the daughter/mother schism in the book, including what is perhaps Anne’s most honest and, for many, problematic, revelation: “I don’t care if mother dies.” The actual diary returns to the deep maternal tension repeatedly: “Just had a big bust-up with Mummy for the umpteenth time,” “she herself has pushed me away, her tactless remarks and her crude jokes” and “I could easily write on every page ‘Pim is a darling!!!! Mummy isn’t!!!!”

It’s worth mentioning Art Spiegelman’s Maus epic again, since it’s rightfully compared to Anne Frank’s diary and seems to be a weird, fragmented relative of it. Pessimistic, pathological, mostly morose and messy, it plumbs the Holocaust and its evil legacy, without Frankean sunshine or joy. But it’s “Prisoner on the Hell Planet: A Case History,” a short comic Spiegelman did in 1972, that I find particularly pertinent sentiment in regard to maternity, with a sentiment flavored very much like Pink Floyd’s psychoanalytical “Mother” song, and so far from the counterbalancing buoyancy of Anne Frank. Spiegelman’s mother committed suicide in 1968, and in the comic he depicts himself dressed in the striped camp-inmate garb. At the funeral a family friend scolds him: “Now you cry! Better you cried when your mother was still alive!” “I felt nauseous…” a caption reads. “The guilt was overwhelming!” Spiegelman relives the last exchange he shared with his mother:

“Artie…you…still…love…me…don’t you?…”

I turned away, resentful of the way she tightened the umbilical cord…She walked out and closed the door!

I can’t help but associate that scene with what Anne revealed in her April 2, 1943 entry:

Oh my, another item has been added to my list of sins. Last night – was lying in bed, waiting for Father to tuck me in an say my prayers with me, when Mother came into the room, sat on my bed and asked very gently, “Anne, Daddy isn’t ready. How about if I listen to your prayers tonight?”

“No, Momsy,” I replied.

Mother got up, stood beside my bed for a moment and then slowly walked toward the door. Suddenly she turned, her face contorted with pain, and said, “I don’t want to be angry with you. I can’t make you love me!” A few tears slid down her cheeks as she went out the door.

I lay still, thinking how mean it was of me to reject her so cruelly, but I also knew that I was incapable of answering her any other way….I saw the sorrow in her face when she talked about not being able to make me love her…She cried half the night and didn’t get any sleep. Father has avoided looking at me, and if his eyes do happen to cross mine, I can read his unspoken words: “How can you be so unkind? How dare you make your mother so sad!”

The shockworthiness of this resentment is assuaged by a later passage in the diary, which is reproduced in full in Folman’s book. Here’s a clip:

The period of tearfully passing judgment on Mother is over. I’ve grown wiser and Mother’s nerves are a bit steadier. Most of the time I manage to hold my tongue when I’m annoyed, and she does too; so on the surface, we seem to be getting along better. But there’s one thing I can’t do, and that’s to love Mother with the devotion of a child. I soothe my conscience with the thought that it’s better for unkind words to be down on paper than for Mother to have to carry them around in her heart.

Woman, Interrupted

“Dearest Kitty, my vagina is getting wider all the time, but I could also be imagining it.” Not exactly the most familiar line from the world-famous diary of Anne Frank, is it? Yet it strikes me as a contender for the most important line, for both its telltale frankness and metaphorical richness.

If anyone deserved to experience the sacred pleasure of sex in her life, Anne did – if not just for her exuberant anticipation of and almost eerily mature respect for sexuality (unspoiled by disappointment or too-common frigidity). “I think what is happening to me is so wonderful,” she rejoiced in her pubescent dawn, “and not only what can be seen on my body, but all that is taking place in inside…I have a sweet secret…” Given momentum by her menstrual onset, her thirst for the erotic burgeoned, sparking admissions that are still surprising and even “scandalous” in these days of faux sexual liberty. She recounts a kiss she shared with a female friend named Jacque, as well as her spurned request to caress each other’s breasts. And she admits a fundamental attraction to the female form:

I go into ecstasies every time I see the naked figure of a woman, such as Venus, for example. It makes me [sometimes] as so wonderful and exquisite that I have difficulty in stopping the tears rolling down my cheeks…If only I had a girl friend!

(Try finding such things in George Stevens’ 1959 biopic.) Much to the relief of traditional pearl-clutchers, Anne’s pubescent spring blossomed into a heterosexual crush on Peter, and their gradual romance was consummated by a genuine kiss, which was a first for both of them.

Following discussion about genitalia with Peter, Anne didn’t hesitate to write down her private speculation on privates, daring the cardinal sin of acknowledging the clitoris’ mere existence, to boot. Below is much of the actual diary entry, which is included (in slightly different wording) in The Graphic Adaptation:

I don’t think a boy is as complicated down there as a girl…He was talking about the ‘mouth of the womb’ but that’s right inside, you can’t see anything of that…[B]efore I was 11 or 12 years old I didn’t realize that there were two inner lips as well, you couldn’t see them at all. And the funniest thing of all was that I thought the urine came out of the clitoris…

… When you’re standing up, all you see from the front is hair. Between your legs there are two soft, cushiony things, also covered with hair, which press together when you’re standing, so you can’t see what’s inside. They separate when you sit down, and they’re very red and quite fleshy on the inside. In the upper part, between the outer labia, there’s a fold of skin that, on second thought, looks like a kind of blister. That’s the clitoris. Then come the inner labia, which are also pressed together in a kind of crease. When they open up, you can see a fleshy little mound, no bigger than the top of my thumb. The upper part has a couple of small holes in it, which is where the urine comes out. The lower part looks as if it were just skin, and yet that’s where the vagina is. You can barely find it, because the folds of skin hide the opening. The hole’s so small I can hardly imagine how a man could get in there, much less how a baby could come out. It’s hard enough trying to get your index finger inside. That’s all there is, and yet it plays such an important role!

Anne didn’t get to experience the sexual discovery and exaltation she so deserved and surely would have treasured. Her genital maturation was both a literal and symbolic bloom, sent to oblivion by death-cultists who preferred thanatotic throes to erotic ones. She never had a chance to date different people or to marry, to work in a meaningful profession, to reap more and more knowledge. Really, if a radical retitling of the diary were needed, it could rightfully be called Woman, Interrupted.

“If You Go, Kitty, I Go With You!”

Brutal crustaceans interrupted Anne on the path to not only womanhood but also lifelong learning and excellence. Like a watch broken and frozen on a murdered body’s wrist, the diary’s open ending marks the time of her virtual demise, the cutoff point at arrest. Perhaps the incompleteness of the diary paradoxically makes the diary complete, nevertheless: just enough freestyling efflorescence of a very human girl saying exactly what had to be said, and not a word more. Maybe additional entries would have been unnecessary.

However, my pessimism and fundamental resentment against nasty, brutish and short life and its ambivalent doling of good and bad fortune, cause bitterness to froth when I consider people like Anne who are struck down despite hopes, dreams and goodness. All that planning, all that caution, all that trust in the end of the war and the liberation of the downtrodden – and the Secret Annex folks (save Otto), as well as benefactor Johannes Kleiman, were obliterated anyway. Anne herself perceived the cyclical violent reality of humankind, putting it this way:

There’s a destructive urge in people, the urge to rage, murder and kill. And until all of humanity, without exception, undergoes a metamorphosis, wars will continue to be waged, and everything that has been carefully built up, cultivated and grown will be cut down and destroyed, only to start all over again!

“Anne Frank had posthumously captured our world,” said Ed van Thijn, Amsterdam’s Mayor back in the 1980s and early 1990s, adding that “she is a symbol because she reflects reality.” And yet, in contrast to her realist realization, she also wrote: “Be brave! Let us remain aware of our talk and not grumble, a solution will come, God has never deserted our people.” Such shameless persistent hope puts me and my habitual hopelessness to shame. Folman deserves praise for being wise enough to present the entire entry for July 15, 1944 in The Graphic Adaptation, since the text exemplifies both Anne’s magnificent maturity and her incisive sense of the inner war between transcendence and nihilism. This passage in particular:

It’s difficult in times like these: ideals, dreams, and cherished hopes rise within us, only to be crushed by grim reality. It’s a wonder I haven’t abandoned all my ideals, they seem to absurd and impractical. Yet I cling to them because I still believe, in spite of everything, that people are truly good at heart…[W]hen I look up at the sky, I somehow feel that everything will change for the better, that this cruelty too will end, that peace and tranquility will return once more.

In cases like this one, I always quote G.K. Chesterton’s “The Position of Sir Walter Scott” (1901):

The centre of every man’s existence is a dream. Death, disease, insanity, are merely material accidents, like toothache or a twisted ankle. That these brutal forces always besiege and often capture the citadel does not prove that they are the citadel.

But, oh, how the citadel was besieged back then.

Heinrich Himmler halted gassings at the camps so that disposal of mass-murder evidence could be focused on, and the victims’ captors were certainly driven to desperation by advancing liberators, but the van Daans [van Pels], Albert Dussel [Fritz Pfeffer], and Anne and Margot didn’t make it. They never rose from the “menacing black clouds” into the open-wide ring in a blue sky. I sometimes guiltily feel a slight disappointment in folks like Anne who succumb to mortality, thinking that they surely should have managed to pull through. Again I’m reminded of Art Spiegelman, who put a relevant crucial scene in Maus. During a therapy session with his shrink, Pavel, Spiegelman credits his father’s present-mindedness and resourcefulness for his survival of the death camps. This offends Pavel, sparking this exchange:

“Then you think it’s admirable to survive. Does that mean it’s not admirable to not survive?”

“Whoosh. I – I think I see what you mean. It’s as if life equals winning, so death equals losing.”

“Yes. Life always takes the side of life, and somehow the victims are blamed. But it wasn’t the best people who survived, nor did the best ones die. It was random!”

I’m not sure if viewing such horrors as random helps, but there it is. It seems that there are good fortune and bad fortune, and sometimes gradations of both; that we spin on a wheel. Countless unscrupulous, rotten people lived through World War II and thrived for decades. The real-life characters of Anne Frank’s story met real-life deaths shortly after they were caught. Simple as that. To inform readers who are ignorant of how everyone ended up, a handy Afterword by Folman covers their fates in detail, as well as the war aftermath and the eventual establishment of Basel’s Anne Frank Fonds.

One of the best episodes depicted and embellished in The Graphic Adaptation involves the police searching the building after a report came from none other than men who’d been burgling the warehouse. Each hushed resident behind the bookshelf is numbered, and the numbers correspond to how Folman thinks Anne would imagine their respective attitudes at execution: Otto “with grace,” Dussel wishing that Anne’s diary were ashes rather than incriminating evidence, Mrs. van Daan putting on lipstick and reassuring herself that she’ll die “as a lady,” Mr. van Daan smoking a final cigarette, Mummy thanking God, Margot rejoicing in her reward for lifelong goodness, Peter regretting that he hadn’t proposed to Anne – and Anne, suffering Joan of Arc’s fiery fate at the stake while clutching the diary and crying, “If you go, Kitty, I go with you!”

That last fictional exclamation unwittingly sums up the whole fortuitous phenomenon of the diary’s legacy, doesn’t it? For surely, in a deep sense, Anne did go with Kitty and speaks to this day from the pages; in the diary she has travelled the globe there and back and there and back again and again.

Anne Frank was a girl of many temperatures and many moods, of high highs and low lows, all of which is illustrated hearteningly and heartbreakingly by Polonsky on a page depicting about 22 Annes of different emotions at the end of the book. With comedian sass she could quip that Gandhi was “holding his umpteenth fast” and that “Hitler delivered a speech saying nothing.” She was a bibliophile who could quote Goethe and Schiller as well as Brer Rabbit. And though she had a visionary’s respect for futurity, she knew the past’s importance, writing that “memories mean more to me than dresses.” Good for us, since Anne performed the sacred duty of giving perpetual life to crucial, exemplary memories. “For in the end, it is all about memory,” Elie Wiesel wrote in Night, “its sources and its magnitude, and, of course, its consequences.”

“I hope no one will ever read you except my dear sweet husband” Anne wrote to her dear diary. Sadly, she would never wed – but she also wanted accomplishment beyond a husband. In May of 1944 she revealed that she’d “made up my mind to lead a different life from other girls, and not to become an ordinary housewife later on.” Her published diary fulfilled that transcendent dream. Thanks to Ari Folman and David Polonsky, and their successful rendition, the immeasurable blessings of the diary seems to radiate from that somewhat silly but deeply meaningful fictional frame of Joan of Arc-dramatic Anne crying, “If you go, Kitty, I go with you!” This made-up line distills the desire that she shared in her diary on April 5, 1944:

I need to have something besides a husband and children to devote myself to! I don’t want to have lived in vain like most people. I want to be useful or bring enjoyment to all people, even those I’ve never met. I want to go on living even after my death! And that’s why I’m so grateful to God for having given me this gift, which I can use to develop myself and to express all that’s inside me!

David Herrle