Rating: ❤❤❤❤

(Throughout this spiel I use this symbol 💬 to denote quotations taken from word balloons in the book.)

Almost everything seems so “meta” nowadays. Of course, there’s always been a lot of metaness in art. Greek choruses are meta; Chaucer is meta; Puck’s closing monologue in A Midsummer Night’s Dream is too. Then there are Ingmar Bergman, Truffaut, Godard and Woody Allen, just a few names from metacinema – which ratcheted up with Being John Malkovich at the end of the 1990s and apotheosized in Joaquin Phoenix’s and Casey Affleck’s tour de force I’m Still Here. Following in the footsteps of Seinfeld, It’s Gary Shandling’s Show and The Larry Sanders Show, self-reference and semi-biographical irony have ruled pop culture for more than several years now, particularly in mockumentary shows such as Curb Your Enthusiasm, Extras and Life’s Too Short, which feature actual celebrities who are surreal blends of fact and fiction, further blurring viewers’ handle on what is and isn’t.

Meta-infiltration also is likely (or unavoidable) in autobiographies and memoir, from Rousseau’s spun Confessions to Klaus Kinski’s Kinski Uncut. And then there are the obviously embellished, fantastic comedic ones: Norm Macdonald’s Based on a True Story, Gilbert Gottfried’s Rubber Balls and Liquor, Chuck Barris’ Confessions of a Dangerous Mind, Dali’s The Secret Life of Salvador Dali, et al. Roald Dahl joked about all autobiographies being filled with “boring details,” but I think the opposite is usually true. Such books rely on carefully selected highlights, curious tidbits and impactful chunks, and dramatized episodes for readers’ pleasure. Few things are worse than dull, straightforward, dry-inventory autobiographies and memoirs.

Then there is yet another form of self-referential literature: graphic autobiography/memoir, which breeds the author’s narrative with the comic-book medium, making what she or he wants to share that much more attractive. Comic-book presentation is especially friendly to humorous works. Much is owed to Harvey Pekar and his American Splendor series for the flourishment and success of this genre. Without pioneers such as Pekar – and Robert Crumb, for that matter, I doubt there’d be stuff like Lucy Knisley’s French Milk, Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis – even the quite recent Anne Frank’s Diary: The Graphic Adaptation.

What is common between these books is use of fictional or factual anecdotes, asides, and actual or visual digressions and/or footnotes. Such abstraction and playful imagery unavoidably create an essential surrealism that sustains whimsy despite depictions of sadness, anger, even tragedy. History and biography are basically determined after the fact, but the natural anarchy of comedy and surrealist art allow for transcendence and metaphysical impact. Perhaps the profoundest and deftest example of this is Art Spiegelman’s world-famous Maus, which combines underground comix’s iconoclastic combustion with Terrence Des Pres-grade seriousness and Freudian-lampooning non-salvific psychoanalysis.

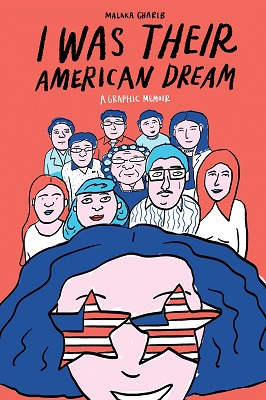

A much more buoyant, positive – and even teleological – graphic memoir is I Was Their American Dream: A Graphic Memoir by Malaka Gharib, NPR journalist and founder of The Runcible Spoon ‘zine. Malaka (which the comic says is pronounced like “Monica”), the daughter of two Filipino immigrants, tells a true story of growing up in America while also negotiating overlapping/conflicting cultures – not to mention respecting and relating to a Catholic mother and a Muslim father. Of course, everything begins formulaically (but not falsely), with parents wanting better lives for their children and emigration to the First World from the Third World (however you want to take those weird, problematic terms).

If there is an older, mentoring sister to I Was Their American Dream, it’s certainly Satrapi’s Persepolis, in so many ways. There’s homeland political/civil strife, a child being sent off to a Western country for safety and betterment, hallucinatory visual jokes and surreal embellishments, tension of tradition, assimilation and discovery, guilt felt for real or perceived moral laxity, and a catalytic crisis that brings enlightenment and self-reevaluation. The opening words of the first chapter of Gharib’s story are familiarly formulaic, but, quite often, formula comes justifiably from fact: “When I was growing up, my mom would always say: 💬‘You have to be better than us.’”

Malaka’s parents were immigrants from the Philippines in the early 1980s, her Dad enthused by and attracted to the United States, and her Mom resistant and partial to her good life at home. 💬“Something inside me clicked and said: ‘Yeah, this is what I want,’” says Dad. 💬“America. Not Europe. Not Australia. Not Canada. Not Berlin, London, Paris. I want open sky, I want America.” This big move shaped both Malaka’s childhood and her adult destiny. From this point on the book chronicles the ambivalent embracement of/divergence from American life.

“On TV, Americans ate Hamburger Helper and Rice-A-Roni, the San Francisco treat,” writes Malaka. “My family ate stuff like monggo*” (The asterisk refers to a footnote: “*Monggo was my most-hated food as a kid.”) Food is always a central example of cultural contrast in such true stories, almost to an existential degree. American extravagances that were disallowed in Filipino culture suddenly become achingly available: “Drinking soda!” “Ordering dessert!” “Lunchables!” A variety of junk fare beyond the preeminence of routine rice in Malaka’s native cuisine.

While on one hand I appreciate this stock element of emigration writings, I also tend to wince at it, because I find it silly that people think of and present their particular cultures as being unique in putting importance on diet and communal dining, as if other cultures – or, more often, “Western cultures” or non-minorities – don’t revere culinary traditions or base their holidays and special observances on what’s created in kitchens. Put it this way: every effing culture on Earth has transcendent, ritualized food preparation and consumption. The cloaked (but not very cloaked) narcissism of overly heritagically-minded folks is what makes so-called multiculturalism actually monoculturalistic: a problematic, albeit posed as “positive,” pride that fetishizes tribes and paradoxically supports a sort of reactionaryism and suspended-in-amber social inertia that contrast the (also problematic) notion of globalism that most of such folks seem to tout.

In briefer terms, I think cultures and races need to get over themselves. I blurt all this in order to address and dispense with the stuff about I Was Their American Dream that bugs me before continuing with what I like about it. Irksome cultural/racial ado flourishes particularly when teenaged Malaka attends Cerritos High, where “the most important question you could ask was ‘What are you?*’” Notice the asterisk, which leads to a delightful, footnote that heartened me at first: “*Later I’d come to learn the flaws of this question…but that’s another chapter, yo!” Does Gharib deliver deliverance from that nosey, restless key question of “diversity”-coated monoculturalism later in the book? Yes. And no.

Cerritos High has students whose ancestors hail from Tanzania, Armenia, Pakistan and India. Fair enough observation. Exposure to different kinds of people is basically a positively fertile situation, especially when all that difference somehow gels and avoids counterproductive conflict. Malaka provides a “Social Map of Cerritos High” and observes that “everyone in high school hung out with people based on clubs, sports, ethnicity. Who’d be my friend?”

A temporary antidote to ethnicity worries? Felicity. Thanks to the 1990s TV show’s influence, Malaka seeks “sophistication in the form of Anthropologie sweaters and Dean & Deluca coffee,” along with a stronger desire “to meet real-life white people” – which, to her dismay, her high school nearly completely lacks. (In a place of a majority of minorities, the majority is minority. See how fundamentally silly “-ity” and “-ities” can be?) To Malaka, whites are cool: “They’re cute.” “They’re on TV and in the movies.” “Clothes and makeup just look better on them!” “They don’t smell like fried fish and fried garlic in the morning.” Then readers are treated to a checklist of “White People Stuff”: such as Weezer, Kurt Vonnegut and Donnie Darko (which is, ironically, a movie conveying a rather bitter critique of white suburbia and affluence). Because of this affinity, other minority student think Malaka is “whitewashed” and being a “poser.”

This identitarian tension continues in Malaka’s matriculation at Syracuse University. “Syracuse was really different from Cerritos,” goes the narration. “Everyone was mostly white!” (💬“It’s just like Felicity!”) Dorm life reveals an ironic difficulty Malaka has with individualizing white girls: “I thought they all looked the same.” Basically, she realizes that she doesn’t “know crap about white people.” (When it comes to social acuteness, one cannot live on Felicity alone.)

And here’s the clincher, as they say: “The most surprising thing about college was that no one asked me the question that was so important in high school. ‘What are you?’ I didn’t anticipate how much I missed being asked.” I’m reminded of anti-paparazzi celebrities resenting eventual absence of paparazzi. What really pissed off Malaka was when people would make the pretentious, guilt-birthed claim that they “don’t see color.” Here I must agree. My Lord, does anyone believe that that’s believable? Then Malaka asks a rhetorical question that is perhaps more annoying than “What are you?”: “Didn’t they wanna know about…my culture?!?” Uhhh…not really. No biggie. Moving on.

Malaka concludes that her uncle “was right about the real world…It was super white,” which compels her to attempt the self-destructive feat of trying “to repress all signs of my brownness.” Now, despite my wariness when it comes to what I call Rainbow Separation (a play on the term Rainbow Coalition, denoting the atomization/tribalization of color resulting from nominal multiculturalism), I’ve never been able to get why anyone would present an attitude or support an environment that shuns “brownness” (a term I find as problematic as “whiteness,” by the way), and I certainly think that repression of one’s genetic/cultural legacy is mentally and emotionally unhealthy. The seesawing of self-segregation and actual prejudice makes discerning between manufactured and real justification of social sensitivity tricky.

Gharib mercifully makes light of such sensitivity with “Microaggressions Bingo,” which includes “triggering” lines that can either be taken offensively or, perhaps more reasonably, laughed at: “Where’s that accent from?” “You don’t look Asian.” “Do y’all eat dog?” “Do you speak Filipino?” “You are so exotic.” “I don’t see color.” (Oh, brother. There’s that fake color-blindness bit again.) Then Malaka slaps us with what might be the most sensible pair of lines in the entire book: “Whatever, dude. Imma just do me.” If only that line, like Voltaire’s Candide’s advice of tending one’s own garden and like, say, some version of Ayn Rand’s radical individualism, could be adjusted to suit society and be maintained somewhat consistently. Sadly, “Imma just do me” doesn’t wash in the politically correct arena.

By the time maturing she moves to Washington, DC, the “What are you?” question becomes a fondly missed thing for Malaka. “I used to love this question because it gave me the opportunity to talk about my ethnicity,” she narrates. “But not everyone felt that way.” For instance, when Malaka asks another woman the question, the woman deadpans back: 💬 “A human.” Malaka presses: “Yeah, but where are you from?” Woman: “Chicago.” Then the terse dialogue turns a little after another question from Malaka:

“Okay, but your family –”

“India.”

“Oh! So you’re Indian!”

“Yeah…So what?”

“Nothing…It’s cool that you’re Indian?

“…I guess.”

Always willing to find humor in so-called serious subjects, Gharib then offers a special page that addresses “The Problem of ‘What Are You?’” Some of the views of different folks reacting to the question follow: “If someone asks you within moments of meeting you, it feels reductive.” “It all depends on timing, topic of conversation, and tone.” “When it’s another ‘other,’ I love it. But when it’s a white dude at a bar, it’s gross.” Wait. What? “Another ‘other?’” Half of the first example is resoundingly true: identity politics, from both positive and negative intentions, are reductive – even dehumanizing. Really, one person on the page said it best: “I never thought of it as offensive until other people told me I should be offended.” That just about sums up thin-skinned society with perfection.

Dad and Mom end up getting divorced, and Dad moves to Egypt, remarrying with a woman named Hala. This familial/national split widens Malaka’s already diverse experience, as well as provides readers with a lot of interesting educative stuff, such as a Tagalog/Arabic vocabulary chart and a Filipino/Egyptian/American social customs chart. Already, thanks to well-timed (and humorous) repetition, readers are familiarized with the word “Alhamdulillah,” which is Arabic for “Praise be to God” and apparently used as ubiquitously as, say, “Hallelujah” in daily life.

Remember, Dad is Muslim and Mom is Catholic, so Malaka adapts to this by hybridizing those religions in her own spiritual habits, such as saying both “amen” and “ameen” at the ends of prayers, and singing the quite Western 💬“parumpapum pum!” while celebrating Christmases with Mom. Malaka’s summers with her father in Egypt are spent enjoying a close paternal bond, absorbing non-American/non-Christian life and processing harsh reminders of human conflict in that part of them world, such as hearing conflagration from the nearby conflict between Israelis and Palestinians during Intifada II.

As if in subconscious divergence from heritage-locked expectations, Malaka falls for a guy named Darren, who’s “great at karaoke,” “extremely dapper,” “tenderhearted” – and a “taong puti” (white person), much to her Muslim father’s dismay. (I wonder if Darren ever listened to Weezer while reading Welcome to the Monkey House.) Eventually, however, Dad gives his blessing, to which Malaka rejoices: 💬“Alhamdulillah!” The result of this pairing? A “big, fat, Filipino-Egyptian-American Southern Baptist-Muslim Wedding,” of course! My, my, what a familiar mark Nia Vardalos’ meta-comedy, My Big Fat Greek Wedding, has left on pop culture.

Like Vardalos’ story, I Was Their American Dream certainly charms with its humor and peculiarity: playful features such as “How to Make This Mini Zine,” a “Fun Page” presenting the “Evil Sand Trap and Fruit Card Game,” celebration of how Malaka’s love of canned pork turned her into “a giant, Spam-eating FB” (“fresh off the boat”), even a modular cut-out paper doll of Malaka with a “Hangin’ in the Quad look,” a “Game Day Look,” a “Frat Party Look” and a “Business School Outfit.” (Sorry. Nothing, not even the author herself, could convince me to actually cut up a graphic novel for extra amusement.)

But, also like My Big Fat Greek Wedding, there’s a basic seriousness, an evident gravity, a tenderness. And the whole book ends up living up to its title, presenting one of the finest dedications a grown child can offer her/his father and mother. “These days, I’ve been thinking about my parents,” Gharib writes. “I never wanted to let them down. They fought so hard to make a life here. I just wanted them to be happy.” Once again, I’m reminded of predecessor Persepolis, in which Satrapi’s father says: “Don’t forget who you are and where you come from.” During a time of great crisis, Satrapi finds herself trying “to forget everything, to make my past disappear,” but she’s saved by underlying self-respect, regaining pride in her Iranian origin. “If I wasn’t comfortable with myself,” goes the narration, “I would never be comfortable.”

Gharib also came full circle, realizing that life isn’t necessarily a matter of “you can’t go back home,” but a matter of “home is where the heart is.” While vacationing in Cairo, Malaka imagines returning there with the children she would have with Darren in the future, and she admits that “I probably won’t be able to translate Arabic for them…or understand the local customs…But they’ll be able to feel the sun on their face, and the wind in their hair…” It should soothe all of our homey hearts that the sun and wind will find us anywhere, without a thought of nativity or how weird our names are. And if you think your weird name isn’t weird, then, as someone once said to a young Malaka: 💬”Maybe you’re just weird, then.”

David Herrle