A spirit with a vision is a dream with a mission.

– Rush, “Mission”

Art, in the end, may be little more than this: convincing people to set aside their natural reluctance long enough to register your vision.

– Richard Russo, “The Gravestone and the Commode”

“Creativity Isn’t Candyland”

I’ve loved Questlove’s name ever since I first noticed it in the liner notes of Booker T. Jones’ masterful The Road from Memphis, but I also, in a slight way, resent the name. Because it’s so cool, so evocative and superhero-like – “a kind of Malcolm X meets Lamont Cranston move,” as he puts it. (If you aren’t familiar with the latter’s secret alter-ego, you need less sunshine and more Shadow). Questlove’s Mo’ Meta Blues memoir reveals that the name was a mixture of A Tribe Called Quest, rapper Q-Tip and…well, the infinitely fertile term “quest” itself. With those two sonorous syllables the enviable tag sums up the human condition, since we’re all on a love quest, in one way or another.

Admittedly, I hadn’t been a fan of The Roots, the hip-hop group for which Questlove still drums and that’s now extra famous as Jimmy Fallon’s house band, until digging the percussion on that Booker T. album. Then I did some retroactive exploration and liked what I heard, further impressed that the group once toured with the legendary Beastie Boys.

In the foreword for Questlove’s somethingtofoodabout: exploring creativity with innovative chefs, my favorite of his books (so far), the late Anthony Bourdain calls Questlove “the Actual Most Interesting Man Alive.” Now, I can’t nod to that, because everyone knows that the most interesting living man is Werner Herzog, but nobody can deny that Questlove certainly qualifies as a Renaissance Brother with eclectic artistic, intellectual and pop-cultural interests.

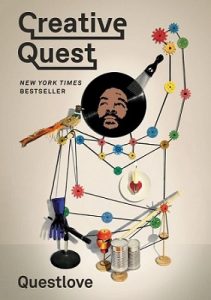

Like many eclectics, his mental pocket brims with pet philosophies, proverbs and anecdotes which recur in his writings and interviews, and these radiate from his primary reverence for all kinds of creativity. So much so that he wrote a new book on the subject: Creative Quest. Of course, he spieled on creativity in his two previous books, but this volume goes much farther, and is more comprehensive and expansive. If a particular statement boils everything down and sets up what would eventually coalesce as Creative Quest, it’s this passage from the Acknowledgements section of the preceding somethingtofoodabout: “Creativity starts before the product and ends long after the product has gone…It takes a form, but then it helps the people who encounter it for a take. It spurs people to ask questions of their own.”

What Questlove seems to intend with this book is to offer inspirational guidelines and reality checks for creatives who may want or need to hone their talents in order to be both more productive and self-satisfying with their work. Teaching creativity is quite a tricky task (or tasky trick), so I always read such books with half-rolled eyes. Some are better than others; some are brilliant and delightful; most are bullshit.

My basic cynicism about this might be due to the nature of my own creative “process,” which is scattershot and haphazard, a paroxysm, a bipolar cycle. If I could, I’d invariably write in only vignettes, lines, stanzas, short paragraphs, since I’m hopelessly aphoristic by default, an artist of notes, marginalia, lists, blurbs, epigrams. And this results from contention with time, as well as practical and emotional pressures. I make observations in what feels like a deluge, plucking figurative little photons and electrons from the proverbial ionosphere, sneezing my ass off while inhaling countless metaphorical allergens. For me, creation isn’t anywhere near streamlined or linear, smooth or soothing.

So, someone like me should benefit to some degree from more experienced and accomplished artists’ wise advice, and I keep this in mind to stay at least somewhat receptive to such from folks who’ve proven their expertise. For a long time I’ve treasured Frederick Franck’s The Zen of Seeing, which presents the concept of SEEING/DRAWING and how visual art can help heal “the split between Me and Not-Me.” Other notables are Julia Cameron’s ultra-popular The Artist’s Way, David Lynch’s Catching the Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness, and Creativity, Creativity: The Perfect Crime by funambulist/trickster Philippe Petit (of Man on Wire fame), Ray Bradbury’s Zen in the Art of Writing, Lin Yutang’s Chinese Theory of Art, Bird by Bird by Anne Lamott, In the Company of Women by Grace Bonney, The Gift: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World by Lewis Hyde, the humorous Ignore Everybody: And 39 Other Keys to Creativity by illustrator Hugh MacLeod, and Zadie Smith’s 2014 lecture on creativity at Case Western Reserve University. I’m pleased to say that Creative Quest has been added to this brief but esteemed list.

The thing in the book that really won me over is Questlove’s bare-wire, realpolitik situating of creativity in a world that’s anything but a wide-eyed captive audience. In regard to bad reviews and general failure in art he accurately agrees that “you’ll feel gutted,” speaking from personal experience. Yet, here’s the snap-out-of-it-and-get-real moment that rattled me, in a good way:

One of the best ways you can cope with the feelings of failure (or the stresses of success) is to embrace a simple fact: the world mostly doesn’t care about you…The world is extremely cluttered. It’s filled with everything. Much of what you do will not land in the middle of a receptive audience.

Hugh MacLeod says as much in a nitty-grittier way in Ignore Everybody: “What a lovely grain of sand you are. Too bad you’re lying on a beach.” Speaking of grains, a title of one of my favorite DJ Shadow tracks comes to mind: “Building Steam with a Grain of Salt” Art is the artistic steam; creativity, personality, authenticity and vision are the salt. “You are the salt of the earth,” goes the Bible’s Matthew 5:13. “But if the salt loses its saltiness, how can it be made salty again?” It’s this quest for creative saltiness (or salty creativity) that Questlove deals with. Both open-ended artistic play and down-to-earth seriousness are necessary for any questing novice or veteran knight. Questlove writes: “Creativity isn’t Candyland – it’s more complicated than that – but there is a game board, with general principles to follow, and I want to sketch it out for readers.”

Besides many illustrative personal techniques and related experiences, Questlove offers little fortune cookie-like advisements at the chapter ends, each one teetering between cleverness and self-helpishness. Some examples: “Attach yourself to people who are doing things you don’t quite understand,” “Find a review of your work and rewrite it to say the exact opposite of what it says,” “Play it backward” and “Begin each day by believing the opposite of everything you believe.” These sent my mind back to Philippe Petit’s Creativity book, which is full of similar sutra-like prompts, such as “Sharpen your intellectual paranoia: remember to suspect – question the question!”

Advice of this kind is well-intended and potentially useful, sure, but how far does following this recipe or that recipe go in the success or failure of art? After all, it could be, as Frederick Franck says, that “there is only one person who can teach you: yourself! There are no shortcuts, no recipes.” Likewise, Questlove stresses in Creative Quest’s afterword that “all the advice in the world won’t help if you don’t get out there and start the perfectly imperfect process of creating.”

Can an Artist Who Doesn’t Drink Coffee Be Trusted?

In a section about creative motivation, Questlove lists some indulgences and rituals that different folks have as prerequisites for productivity. “So many people say coffee,” he writes. “I don’t drink coffee.” OK. Here he’s crossed a line. Time to close the book! Well, not really. He can be forgiven for such a sin, albeit reluctantly. His good point overrides his beverage-heresy. What Questlove wisely means is that artists shouldn’t deny whatever it is that produces conduciveness for creative activity. For me, as trite as it sounds (and is), a trenta-sized cold brew from Starbucks is essentially a matter of life and death. And, usually, affective music (from the Quartet/post-Quartet John Coltrane to Pharoah Sanders to Ennio Morricone to St. Vincent to PM Dawn to The Ocean Blue to New Order to Annie Lennox to the Buzzcocks to The Who to SZA) also is a must. Such aids might seem superfluous and/or selfish – but superfluity and selfishness themselves are essential to realizing creativity. Questlove puts it better in this passage:

Whatever your personal preference, no matter how significant or how trivial, if it’s a source of pleasure, and in denying yourself that pleasure you’ll be entering a state where you think about it all the time, then you are working against your own creativity.

In regard to the other crucial must for creativity, time, Questlove’s easier-said-than-done guru pearl is “Take time to make time.” “When you are making art, you are stealing time,” says Hugh MacCleod. This is so crucial to the artistic life. My mind goes to something Catherine Drinker Bowen wrote in her splendid biography on Benjamin Franklin: “With money a man bought not only independence but he bought time, that most precious commodity, to use at his pleasure.” In Catching the Big Fish David Lynch says that freedom and art are mutually contingent. “And it seems, I think, a hair selfish,” he writes. “But it doesn’t have to be selfish, it just means that you need time.” His point, which sums up my own artistic frustration, continues: “[I]f you know that you’ve got to be somewhere in half an hour, there’s no way you can achieve that. So the art life means a freedom to have time for the good things to happen.” It’s no surprise that Lynch is a serious proponent and practitioner of Transcendental Meditation – and that he’s a chilled out, patient and ponderous person. Questlove also touts therapeutic mental concentration and calls it “micro-meditation”: a method of clearing the artist’s path, a focused state in which “you have to be both entirely consumed by the moment and also a million miles away.” And he deals with creativity’s ambivalent situation this way:

Creative things happen to creative people, especially when they let themselves go to the Zen of the moments, when they don’t allow themselves to be paralyzed either by overthinking or by laziness. They have to be in the sweet spot between the two.

Hugh MacLeod’s Ignore Everybody presents a cyclical maneuver of “enrich” and “simplify,” which seems to coincide with Questlove’s idea of paradoxical presence/absence and complication/distillation. “One of the most important strategies is negative affirmation…,” says Questlove. “Carve out the negative space around your idea…It’s sometimes hard to see the heart of an idea, so chip away at all the things that aren’t the heart.” Yet again The Zen of Seeing’s wisdom rings: “The eye that follows the sweep of the earth intuitively selects hillocks and clumps of trees that define the space; it picks up and leaves out forms, details. Drawing here becomes the art of leaving out.”

David Byrne offered similar advice, which Creative Quest’s author boils down to this: “Don’t imagine what you will become – imagine what you won’t become.” In other words, Questlove asks, “What are you as an artist, and what aren’t you?” Self-identification gets more complicated when artists of whom we are emulous are analyzed. “We take our ideas where we find them,” he continues, “and largely we find them in the works of other artists.” For instance, he admits the extent of his stylistic absorption of previous drummers. On Wise Up Ghost, an album The Roots did with Elvis Costello, he’s “drumming on it as Steve Farrone,” who kept the beat for Average White Band and Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers. Questlove seeks “to re-create the drumming of other artists from the past…I try to inhabit their spirit.” In fact, on The Tonight Show he uses different-tuned snare drums that are personalized to drummers’ specific sounds. This, of course, raises the question of his artistic identity: “[A]m I creating anything that’s uniquely me? Or am I just a Frankenstein’s monster cobbled together from all the perfect drummers I know and love?”

Facing this, Questlove contends that there’s no actual “pure originality.” I’m reminded of something Gilbert says in Oscar Wilde’s ever-fruitful The Critic as Artist: “The mere creative instinct does not innovate, but reproduces,” if it’s devoid of the critical spirit. To illustrate how critical creators’ personalities remold established works he mentions the genius of Anton Rubenstein: “When Rubenstein plays to us the Sonata Appassionata of Beethoven he refers to not merely Beethoven, but also himself…Beethoven reinterpreted through a rich artistic nature, and made vivid and wonderful to use by a new and intense personality.” (So rest assured, Quest. Your spirit inhabits your mentors’ spirits as well.)

Art history is like rivers flowing into seas and seas flowing into rivers, and there’s a vast ongoing connection in creativity in general. Questlove goes as far as to claim that “creativity creates connectedness.” It’s no surprise, then, that he writes a lot about collaboration, though he admits both its positive and negative potential. “The most common problems in collaboration, in my experience, revolve around resentment,” he says. “One person feels that his or her ideas aren’t getting enough of a hearing or that they’re being twisted to suit the other person’s ideas.” As I shared in my review of U-God Hawkins’ splendid Raw memoir, John Cleese described Monty Python’s later strained collaborative work in a way that’s applicable to creative groups in general:

One of the problems is that at the beginning of a group’s life they huddle together for warmth. Then as they go on and by and large prosper, they develop their styles and they don’t want so much to give up their own style in order to go back to a group style.

This is none other than the truth of the fundamentally individualistic nature of art, which must happen inevitably sooner or later, rising to the surface. And it’s why I tend to shun any metaphysic that endorses purposeful vacation from or denial of the self, the ego, the personality, whatever you call it. I’m mostly numb to the whole “something larger than myself” thing, and I think, hyperbolically enough, that concept is the top of a slippery slope into anti-humanism, collectivist subsumption and problematic martyrdom. In other words, while I appreciate the sense of the Emersonian Over-Soul, I almost never take claims of achievement of ego-vanquishment seriously. Every one of the folks who actually try to achieve that either go mad, commit suicide or fake the whole thing (usually quite poorly).

Questlove describes his micro-meditations as “brief and intense phases of departure from the self,” but I assume that he, who is undeniably a very distinct individual, considers such departure to serve as a sort of pressure valve or palate-cleanser rather than flight or divorce from selfhood. Curiously, Questlove’s reference to another kind of departure, that of branching out from one’s usual art or even doing something radically different, seems to imply a central self from which creativity flows: “You depart, but the countermovement is return. You’re not a nomad. You’re not rootless.” (Of course, a member of The Roots should deny rootlessness.) Also, at the end of the book he says, “There is species-wide programming, and then there’s individuality,” and creativity happens within that overlap.

I understand the need for compromise and even sensible ego suppression for the sake of group creation, but when it comes to solo artists, independence and singular or top-heavy control are to be expected. (I’ve a huge soft spot for auteurs.) In the music realm, she or he may be backed by either an established group or session players, but the one with both the most attention and burden is him or her. That person becomes a brand of its own, and fans expect that brand to be infinitely recognizable and consistent. This often means that though a music artist debuted as a mold-breaker, that same artist can easily become trapped in her or his own mold, and anything that’s seen as tampering with or discarding that mold is fair game for scorn.

Questlove uses Eminem as an example of an ingenious, personality-driven, real-deal artist, at least in the rap/hip-hop realm:

Take Eminem. When he first appeared on the scene, lots of the conversation around him dealt with his authority. He encouraged that line of thinking because it helped to raise his profile, and also because he must have been absolutely secure in the fact that he was authentic as anyone – as authentic as Run D.M.C., as authentic as Rakin, as authentic as Chuck D. He was doing something a little different than any of them, but he was doing it completely authentically.

Also, impressively, Questlove doesn’t allow repressive/paranoid/art-killing political correctness to dampen his respect for Eminem’s artistry. “Eminem didn’t put a should-I-really-say-that cap on his idea,” he writes. “He didn’t put a socially acceptable filter on it. He didn’t put a good-taste governor on it…He went from nothing to something thanks to an idea that he had.”

(I wonder if Eminem drinks coffee.)

Birth/Breadth of the Cool

I applaud Questlove’s meritocratic esteem for Eminem, as well as for the Beastie Boys. Too much nuanceless, puritanical busybodying about “cultural appropriation” toxifies art and demonizes artists. As a rule, cultural creations eventually belong to neither monopoly nor majority, really. Creation breaks out from certain cultural groups and regional trends, for sure, but the rapidity of social sharing and exposure prevents any significant stasis in regard to This or That type of what’s hip and worthy. I agree with Penn Jillette that “cultural appropriation can be the most important good thing possible,” which he said on Pete Holmes’ podcast.

Something that pops up in Creative Quest irked me at first, until I realized what its author seemed to mean. I’m often skeptical (or bored) by racialized takes on things, since I tend to find much problematic collectivism involved in both negative and positive cultural/artistic segregation, due to my distrust of racial pride and its chauvinistic/abuse-prone implications. The divisive, often inaccurate and/or obtuse insistence on “This is ours!” blasphemes the melting-pot concept, shows the actual monoculturalism beneath so-called multiculturalism and denies cultural fluidity on this interconnected, Internet-affected planet.

The other side of the monocultural coin is “This isn’t ours!”: a grudge that is starkly exhibited in academic/cultural antagonism toward the importance of Shakespeare, for instance. There are folks who sneer at the general Western canon, rejecting ole Shake as irrelevant to this or that non-white heritage. When faced with this, I tend to downplay my slightly radical Bardolatry (a la Harold Bloom) while politely stressing that such omission is deficiency rather than healthy heritagical flexion, then referring the other party to American-treasure James Baldwin and his 1964 piece “Why I Stopped Hating Shakespeare.”

After realizing the error of his race-based condemnation, Baldwin found a spiritual/existential kinship between Shakespeare and, in his words, “my black ancestors, who evolved the sorrow songs, the blues, and jazz, and created an entirely new idiom in an overwhelmingly hostile place.” Tapping into the inherent power in and expressive utility of the English language instead of repudiating it as oppressorspeak, Baldwin says he discovered the self-production value of the language and “its candor, its irony, its density, and its beat.” In Shakespeare’s language he found more enlightenment about himself and his ancestry – perhaps even the essence of the inimitable sound of jazz. “I was listening very hard to jazz and hoping, one day, to translate it into language,” Baldwin writes, “and Shakespeare’s bawdiness became very important to me, since bawdiness was one of the elements of jazz…”

For me at least, the best way to appreciate cultural origination and contribution is to acknowledge the catch and then throw the fish back into the water, so to speak. Take the blues and jazz. By now no self-respecting person should be ignorant of the key precursors and roots of these music genres, but nobody ought to feel as either sentinel of or interloper in them. An especial adorer of old acoustic blues, I have my own spiritual relation to a lot of the stuff by Son House, Rev. Gary Davis, Blind Boy Fuller, Pink Anderson, Ma Rainey, et al, claiming spiritual empathy if not just for my being a fallen human in a capricious, sorrow-filled existence. (“Everybody have the blues!” Leadbelly proclaimed, and Big Bill Broonzy sang, “This train don’t carry white or black, everybody ride it is treated just alike.”) And, since I consider blues the prophet and jazz the messiah, I treasure jazz as the quintessential American art form (next to, say, comic books).

Anyway, while spieling on the intersection of politics and art, and vice versa, Questlove brings up the popular “idea that black creatives are somehow out of this world – that they’re opening with a level of talent or genius that can’t be rationally understood.” From this radiates the phenomenon of so-called “Black Cool”:

There’s an idea that circulates through the culture, Black Cool, that identifies the ways in which African American artists occupy (or used to occupy) a spot in the culture where they serve as trailblazers in terms of fashionable affect and cutting-edge ideas…The bloom may have come off the rose to some degree…It’s an opportunity to stop addressing the politics of black creativity and talk about the trickier hope that black creativity might become, in some sense, productively apolitical.

In regard to politics, or, more specifically, partisan affiliations, I’m reminded of James Baldwin’s “The Artist’s Struggle for Integrity,” in which he says that “all artists are divorced from and even necessarily opposed to any system whatever,” due to their duty to expose the illusoriness of “all safety.” As for perceived extraterrestrial “black creativity” mentioned in the excerpt above, my mind goes instantly to “The World and the Jug” essay by Ralph Ellison (literary heir to non-black favorites such as Dostoyevsky, Melville, Whitman, Hemingway and Thoreau – and whose namesake is Ralph Waldo Emerson, for goodness’ sake) brilliantly criticizes Irving Howe’s interpretation of Invisible Man: “Howe makes of ‘Negroness’ a metaphysical condition,” says Ellison, later insisting on essential transcendence beyond race in regard to art. “While I am without doubt a Negro, and a writer, I am also an American writer,” he wrote in the same essay. This reminds me of James Weldon Johnson’s prefaces to The Book of American Negro Poetry (1922) and his pride in the widespread laudation of ragtime’s quintessential Americanism. Johnson noted both the seminality of and the syncretism of creation:

This power of the Negro to suck up the national spirit from the soil and create something artistic and original which, at the same time, possesses the note of universal appeal, is due to a remarkable racial gift of adaptability; it is more than adaptability, it is a transfusive quality.

As Jeffey Melnick writes in A Right to Sing the Blues, “for [James Weldon] Johnson, it was a given of the modern urban world that any vision of discrete ethnic property had to give way to the realities of porous boundaries.” And Questlove’s apparent wish for something wider than “black creativity” echoes Johnson’s hope for and expectation of expansion beyond “Negro” writing: “the sooner they are able to write American poetry spontaneously, the better.” Which brings us back to “The World and the Jug”:

If Invisible Man is even ‘apparently’ free from ‘the ideological and emotional penalties suffered by Negroes in this country,’ it is because I tried to the best of my ability to transform these elements into art. My goal was not to escape, or hold back, but to work through; to transcend, as the blues transcend the painful conditions with which they deal.

Obviously, I’m wary of tribal/sociopoliticized art in general, careful not to curtail Coolness’ vast breadth, and Questlove’s astute balance between racial/cultural identities and creative cosmopolitanism impresses me greatly. I dig the imagery of good shrapnel for symbolizing artistic expansion and line-blurring, which I derive from something Public Enemy’s Chuck D. said in a Reuters interview several years ago: “Rap and hip-hop altered the musical soundscape audibly and visually with shrapnel impact from many different directions. Beyond the music, the culture was ingrained into many hearts, heads and souls.”

If it weren’t for cultural cross-pollination, art would be much less vibrant and versatile. Imagine a world where Rev Run (formerly DJ Run) wouldn’t base a rap song on Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Sweet Home Alabama” (of all things), where Run-D.M.C. and Aerosmith couldn’t team up to bring down the house in the 1986 remake of “Walk This Way,” where Brazilian and African music hadn’t swirled into Paul Simon’s The Rhythm of the Saints, where U2’s The Joshua Tree masterpiece couldn’t become one of the profoundest American (yes, American!) albums of all time, where Led Zeppelin hadn’t emulated cats such as Muddy Waters and where P. Diddy’s “Come With Me” wasn’t built on Zeppelin’s famous “Kashmir” guitar riff, where Debussy wasn’t exposed to ragtime and therefore didn’t contribute to the evolution of jazz, where hybrid bands such as The Police, The Clash and The Red Hot Chili Peppers would never exist, where ska music never would’ve coalesced, where white American/British punkers never would’ve fueled Bad Brains, where Japanese art couldn’t color James Whistler, where Joan Miro hadn’t channeled Hieronymus Bosch, where Sidney Lumet never impressed Spike Lee, where Tarantino didn’t synthesize the likes of directors from Don Siegel to De Palma to Godard to Takamori to Gordon Parks Jr. to Sergio Leone, where Kurosawa hadn’t inspired Leone or George Lucas, where Disney didn’t influence manga/anime – and vice versa, where Melville hadn’t inspired Charles Johnson’s Middle Passage or William Blake hadn’t inspired Paulo Coelho, where an occasional stuffed shirt like Amiri Baraka couldn’t admit the greatness of, say, Tennesse Williams, or where writers such as Harlan Ellison and Fritz Lieber hadn’t helped shape the genius Octavia Butler.

Which brings us to my favorite subject in Creative Quest: curative curation.

Curation

In order to freshen one’s art and to open the mind to new ideas, Questlove suggests moving into different areas or environments, and prompting oneself to experience different art forms first-hand. “When you’re practicing a creative discipline, practice another one,” he says. “If you are a singer, draw cartoons. If you are a writer, try to sculpt a little bit.” “Rebel against your own inclinations,” Philippe Petit likewise suggests. “You love classical music? Put on some heavy metal!” To me, this seems like a no-brainer. Being eclectic should be a lifestyle, not an exercise. Diving into a wide spectrum of interests sharpens your critical acumen and strengthens your authority, based on knowledge-earned nuance and insight, to offer constructive criticism and even to snobbishly like stuff that is deemed unlikable by an also snobbish or vulgar majority. This is why the following passage from Questlove’s Mo’ Meta Blues thrilled me so much:

If a great artist makes an album that critics don’t like, or that they’re suspicious of, I make a beeline straight for that record. I’m the music snob who takes up the ‘wrong’ records, like U2’s Rattle and Hum, which was maligned for being slavishly imitative of American music.

And it’s why I can stand here and plainly declare before every reader that I love (and cry during) The Bodyguard movie, starring Whitney Houston and Kevin Costner. So there.

After some riveting stuff about “calculated spontaneity,” distinguishing between “back-loaded and front-loaded types of creatives” and Type A and Type B artists (the former being “directed toward product” and the latter more loose-ended), Questlove gets into how technology is literally brain-changing and how over time our brains have gone from being “containers” to being “retrievers,” thanks to the multitask-oriented Internet and vast exposure to all kinds of information and social media. “Now in the twenty-first century, creative life also includes some management of other people’s creativity and the overlap between yours and theirs,” he says. “To put it a different way: you can be an artist, but you also have to be a curator.” And the musical development of sampling is presented as an excellent example of such curation:

Then hip-hop entered an era of sampling. Technology made it possible, and aesthetics follow technology…It was simple at first and then, in the hands of the Bomb Squad [on Public Enemy’s It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back album], it became elevated into high art…They were able to take existing materials and make something bracing and new from them.

Far from deserving castigation for being lazy, unoriginal or theft, sampling has certainly enriched our musical sensibilities. It also draws attention to the fact that, as well as being ideational, creativity is material. Of this Questlove writes: “[T]he Bomb Squad’s materials happened to be certain pieces of technology, samplers and sequencers, and a world of recorded music that they could feed to that technology.”

I must cite Wilde’s The Critic as Artist again because something in it can be applied to sampling, which, obviously, was written long, long before such technology. One of two speakers, Gilbert, touts the creative importance of criticism, explaining that it

works with materials, and puts them into a form that is at once new and delightful…Indeed, I would call criticism a creation within a creation. For just as the great artists, from Homer and Aeschylus, down to Shakespeare and Keats, did not go directly to life for their subject-matter, but sought for it in myth and legend, and ancient tale, so the critic deals with materials that others have, as it were, purified for him, and to which imaginative form and colour have been already added.

One of Questlove’s go-to stories is what he sees as the seminal moment for sampling in the 1980s: The Cosby Show’s “A Touch of Wonder” episode, in which guest-star Stevie Wonder captured some of the Huxtables’ voices on an SK-1 synthesizer and played them back with music. I remember watching it for the first time back when I was a boy, and I’ll never forget how magical it was, particularly Theo’s funky “jammin’ on the one” phrase. Questlove claims that “hip-hop changed forever” in that moment. “It remade hip-hop production right there, on the spot.” Of course, Wonder had experimented with rudimentary sampling as far back as his Journey Through the Secret Life of Plants album. And hadn’t Pink Floyd sampled in Atom Heart Mother almost a decade before that?

By the way, to really play Puck here, I must give props to Frenchman Edmond Rostand’s co-invention of hip-hop when he had Cyrano de Bergerac school the Viscount on how to properly whip against opponents’ and gossips’ insulting quips about his profound proboscis (like reversing slurs and epithets by humorizing them), and followed up by extemporizing a witty rhythmic, syncopated-rhymed ballade – seventy years before Kool Herc and The Last Poets!

Curation-enabling technology also provides a potentially problematic glut of information, trivia, images, videos, you name it. In a word, it allow for powerful distraction from creation. “A ‘non-creative’ environment is one that constantly bombards us…overloads our switchboard with noise, with agitation and visual stimuli,” Frederick Franck wrote long before the Internet, PCs, laptops and tablets. “Once we can detach ourselves from all these distractions, find a way of ‘inscape,’ of ‘centering,’ the same environment becomes ‘creative’ again.”

In the same spirit, Questlove writes: “I was always in the Internet. I was always in the middle of all the mouse clicks. What I had to learn was how to get out of something before I got back into anything else.” To combat counterproductive distraction, he advises the artist to “let yourself go to the sense of being disconnected and meaningless. Let it wash over you and drown you a little bit before you come up gasping for air. Creativity is a fight against that insignificance.”

He also refers to poet Joseph Brodsky’s 1989 commencement address at Dartmouth College, which presents a peculiar – and sobering – concept of boredom and time, and how passion and pain can motivate creatives. Part of what Questlove quotes from the speech are the following inspirational lines: “When hit by boredom, let yourself be crushed by it; submerge, hit bottom. In general, with things unpleasant, the rule is: The sooner you hit bottom, the faster you surface.” Since I’ve been otherwise familiar with Brodsky’s address, I’ll include a little more to clarify the whole boredom thing:

The reason boredom deserves such scrutiny is that it represents pure, undiluted time in all its repetitive, redundant, monotonous splendor…For boredom speaks the language of time, and it teaches you the most valuable lesson of your life: the lesson of your utter insignificance. It is valuable to you, as well as to those you are to rub shoulders with. You are finite, time tells you in the voice of boredom, and whatever you do is, from my point of view, futile.

Mother Mercy, that hurts. Because it’s so true. Echoing both Brodsky and, unwittingly, Hugh MacLeod’s “lovely grain of sand…lying on a beach” wake-up call, Questlove is every bit as profound in this passage:

One of the best ways you can cope with the feelings of failure (or the stresses of success) is to embrace a simple fact: the world mostly doesn’t care about you…The world is extremely cluttered. It’s filled with everything. Much of what you do will not land in the middle of a receptive audience.

Later Questlove semi-rhetorically asks, “Does art need an audience?” Classifying himself as “a commercial artist” who must please a public audience, he gives commercial art positive credit for imposing a deadline on artists and preventing procrastination.

By now you’re used to my constant swinging back to Franck’s The Zen of Seeing, so I needn’t apologize for another relevant quotation from it: “Any work of art motivated or tainted by the slightest consideration of competitiveness, money, sensation, is automatically devoid of Zen…Authentic, personal experience is both aim and method of Zen.” Now, while I get what Franck’s driving at here, I think he’s too hardcore, especially since I’d give just about anything to have a fifth of the success and validation he – or Questlove – has obtained. Artistic integrity needn’t be a casualty of commercialism, the market and audience expectations.

As Questlove reiterates, it all depends on one’s strength of authenticity. Despite the commercial aspect of his work, he says, “I have to use it to communicate a private world.” To add to that, one can’t deny that well-marketed and widely exposed art also gives the artist the privilege of regarding her or his work more as an apart object, and therefore maybe easier to evaluate and learn from. “When you’re on the outside of your own work looking in,” writes Questlove, “you’ll be able to see the overall shape of it…”

Granulation and Graduation

I’m ambivalent about positivity in regard to one’s creativity and artistic production, because I do think that art needs an audience. Trees that fall unheard in forests don’t make sounds. The Hallmark-card fluff about doing art “for myself” has never flown for me, and feel-good stories about posthumous discovery and fame of obscure, ignored artists’ work don’t feel good. They’re sad and pitiful.

To a large degree, it seems a lot easier to even have an effective process, a clear perspective and results-reaping motivation when one’s in the position of fame and in-demandness. Yes, Questlove is right to say that “creative things happen to creative people,” but successful people tend to attract more success, just as money comes to money.

Yes, according to his Mo’ Meta Blues, Questlove wasn’t born a star, nor was his rise from obscurity without effort, discomfort, error and setbacks. His upbringing was somewhat humble, and he says that he’s still traumatized by finding errant mice caught in traps in his house back when he was a boy. Reading that, I thought: Mice? Man, we had fat effing rats slinking around our house and convulsing in traps during my lean youth – on the reg!

However, I’m a man rather than a mouse, so, pendulous between aspiration and desperation, determined to avoid total granulation and eager for further graduation, I tread on in my own life with a glass half full of overcast cynicism, occasionally allowing smart, talented, lovely folks such as Questlove to pour a little sweet insight and light into the other half. Though Creative Quest has much to pour out, perhaps the following passage is Questlove’s profoundest, most quenching offering for me. And for it I thank him, as well as wish him continued flourishment.

Studies have shown that creative people tend to be more sensitive to the feelings of others and to fluctuations in the social fabric around them. At the same time, they are often less equipped to deal with those things. The result can be withdrawal from the world. Defense mechanisms, depression. Creative production is not only a way to avoid those pitfalls, but a way to connect those people to the rest of the world.

Ever since 2007 my default go-to in regard to the compulsion, obstacles, disappointments and passion of creators has been Mark Knopfler’s “Let It All Go” on the Kill to Get Crimson solo album. Any struggling artist who needs some relatable, poignant, stirring shorthand about the common trials and assailing regrets of the art life should listen closely to the song’s lyrics. But if a lengthier, rounder, more positive and anecdote-rich resource is desired, I recommend Creative Quest.

Returning to Questlove’s “the world mostly doesn’t care about you” and Hugh MacLeod’s “a lovely grain of sand…lying on a beach,” I’ve enough self-awareness and purposeful humility to admit that, relatively speaking, I’m a fraction of a fraction of a fraction of a grain of sand. But I take my fractional minuteness with a grain of salt, making sure to remind myself that each ego also is a Gibraltar Rock and that the liberated creative spirit, through both pitfalls and windfalls, builds steam, builds steam, builds steam, builds steam, builds steam.

David Herrle