Rating: ❤❤❤❤❤

First this, first that. Sometimes I’m impressed, often I’m not. Too many firsts. Maybe the “who’s first” thing has gone haywire, and the fact of someone being first in something tends to become a sacralized value in itself. (Or maybe I’m more interested in lasts.) After all, along with laudable firsts there are pathetic firsts – even evil firsts. And, if my ontological aplomb may be excused, all of us are firsts: you are the first person to be you. (And you’ll be the last you.) But, all kidding aside, I get why celebration of individuals who are firsts exists. It’s a launch point, at least, serving as a remarkable introduction to the career(s) and biography of a person who, for whatever reason, seems to deserve inclusion under the esteemed category of “historic.”

Nowadays, fixation on the gender aspect of first-timers (achievers, historic figures) seems to surge pervasively in American society, whether it’s sincere or forced for the sake of facades of public righteousness. And it seems that the trend reparationally favors females more than males. While such focus in itself is not necessarily a bad thing, I do tend to suspect or, at least, downplay it, since the attitude overestimates a dearth in recognition of praiseworthy females while underestimating the individualistic, extra-gender merit of this or that exceptional person. In other words, words such as “fierce,” empowered” and (most yawn-evoking) “strong female” tend to gimmickize the wide and varied cast of biography subjects and turn off identity-politics despisers like myself.

For every “Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley in Alien was my first exposure to a tough-minded, capable woman of agency in movies” there’s a Joan Crawford’s Vienna in Johnny Guitar; for every Jennifer Lawrence there is a Marlene Dietrich, a Patricia Neal, a Tamara Dobson. “Woke,” effectual, smart, formidable females have been popular in fiction for quite a long time. Think Shakespeare’s Cordelia and Rosalind, or Octavia Butler’s protagonists. Or, farther back, Chaucer’s Wife of Bath. And, to give credit where it’s due, what would good slasher films be without their magnificent Final Girls (which is a topic for a whole other digressive, somewhat-divergent-from-Carol-Clover spiel)?

As for reality, innumerable females have been movers and makers, and one big reason why certain women are often taken as surprising anomalies is the lazy myopia of these days’ fetishization of the so-called “enlightened” present, a temporal/cultural narcissism blind to centuries of excellent females. History is a photomosaic: a picture comprised of many smaller pictures, and many of those smaller pictures depict female individuals. More than many of us tend to think.

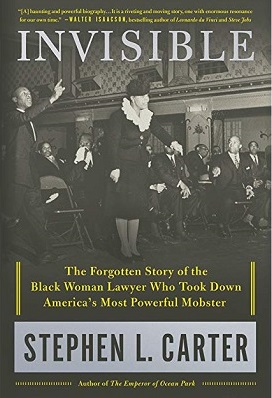

Abigail Adams, Mary Wollstonecraft, Pauline Kael, Cleopatra, Governor “Ma” Ferguson, mail-carryin’/rifle-wieldin’ badass Stagecoach Mary, Catherine the Great, Queen Elizabeth I, Queen Victoria, codebreaker Elizebeth Friedman, Harriet Tubman, Margaret Thatcher, Margaret Fuller, Ayn Rand, Mother Jones, chemist Rosalind Franklin, Annie Lennox, and NASA’s mathematician triumvirate Katherine Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan and Mary Jackson. Oh – and Rihanna. To say that there are countless more examples suffices, but let’s add a particular historic woman: Eunice Hunton Carter, whose relatively underrated life and career are given due attention and honor in Stephen L. Carter’s Invisible: The Forgotten Story of the Black Woman Lawyer Who Took Down America’s Most Powerful Mobster.

Former Thurgood Marshall law clerk, Yale Law Professor, and author of a novel called New England White and a must-read, impactful, engrossing and wisdom-packed book called Reflections of an Affirmative Action Baby (which addresses the many cons and pros of Affirmative Action), Stephen Carter happens to be the grandson of the biography’s subject, so both the pride and the self-psychotherapy of being a blood relative enriches and deepens his careful, caring study rather than subjectively cataractizing his vision. In the introduction, Carter expresses in so many words what I stipulated in the opening paragraphs above, apparently implying that truth is often stronger than fiction:

In the fall of 2014, two episodes of HBO’s Boardwalk Empire…featured a black female lawyer…The role was small. She had perhaps two lines. Still, viewers were incredulous. Online comment threads swiftly filled with mockery: Ridiculous. Anachronistic…

But they were wrong. My Nana Eunice was real…

Immediately, while considering that excerpt, I associated to a particular line in New England White: “…whenever [Julia] mentioned that her family had been architects for seven generations, even most black people looked at her pityingly, as if she exaggerated a tale of her forebears building their own shanties.” Invisible is intended to make Carter’s grandmother visible in at least history combers’ eyes. It’s a testament to the unlikely but not so difficult to believe story of the astute achievement and expertise of a black woman who was a “granddaughter of three slaves and one free woman of color,” and greatly influenced the American legal system, as well as contributed to the fertile froth of the Harlem Renaissance.

Throughout the book, Carter uses pet terms “darker nation” and “sassiety” a lot, sometimes addressing the tension of simultaneous apartness and inclusion of blacks in the United States, especially back in Eunice’s day. “Darker nation” in particular also is a key element in New England White, in which the son of the two protagonist parents rejects their heritagical reverence: “I’m not interested in that crap. The old families. The traditions. All that bullshit…I’m trying to discover the dark matter, and he’s worrying about the darker nation.” History overflows with dark matters, within and without the so-called “darker nation,” which is why an enlightened champion of light such as Eunice was needed and destined to stand, largely alone, against the growing deadly criminal cabal in gangster-heyday New York City.

“No one had ever seen anything like this,” Carter writes about Eunice’s being appointed Special Sessions head, and earning the equivalent of $112,000 per year nowadays. “White men, well trained, graduates of the top schools, all taking orders from a Negro. A Negro woman.” It’d be difficult to avoid not referring to this situation as a famous First, but the problem of what I call historical segregation lurks within doing so. In Reflections of an Affirmative Action Baby Carter calls it the “’best black’ syndrome,” by which blacks are “measured by a different yardstick: first black, only black, best black.”

However, the basic justification of this particular First history story lies in the fact that, not unlike little (but big!) Ruby Bridges or graceful Dorothy Counts, Eunice, who seemingly unflinchingly traversed a less-than-hospitable (to say the least) arena, rose above – and knew that she deserved “her standing at the summit of the Great Social Pyramid.”

What better way for an aspirational lawyer to sink her teeth into the Big Apple than to take aim at its grifting, grafting, ugly Goliath at the time: the Mafia? By the mid-1930s it seemed that household-name, and thorn in law and order’s side, Lucky Luciano was, to evoke Eliot Ness, untouchable – until Eunice had the idea to nab him on prostitution, seeing that particular racket as a viable vulnerability.

Another notorious household name, Dutch Schultz, had wrested domination of Harlem from the local Black Kings and Black Queens, but eventually Luciano became the law’s primary target. Head of the future Genovese family, “Charley Lucky” founded what was called the Combination, a sort of association based on a democratic network. During a push to investigate Dutch Schultz’s activities, the governor of New York appointed Thomas E. Dewey as special prosecutor. In turn, Dewey hired Eunice along with 19 other lawyers, later claiming that he “hired Mrs. Carter the first day I met her…She has made good, and commands the respect of the bench of the city.” Carter addresses the veracity of Dewey’s claim:

Certainly there were whispers in the press that she was a mere token, although nobody dared use the word…Dewey himself always insisted that he offered Eunice a place because of her excellence, and perhaps that was the truth. From Eunice’s point of view, however, the motivation behind her hiring was irrelevant.

Dewey was basically disinterested in Eunice’s prostitution angle, so “only Eunice saw the larger picture,” yet “she mined the stacks of citizens’ complaints that others ignored, and she found gold”: widespread systemic corruption that benefited the Mob. “Fixed cases,” Carter writes. “Forgetful cops. Bribed judges. Crooked lawyers. Untouchable madams. Invulnerable brothels.” A crime syndicate, involving high levels of the legislature and judiciary, sustained the grift, the graft and the ugly in New York City.

Thanks to a rival gangster conspiracy that included Luciano, Schultz was assassinated and removed from contention. Meanwhile, Eunice accessed a crucial list of racket information and evidence of its central control. But, even though compelling wiretap evidence existed, she was alone in her diligence. Dewey’s hesitance came from a strategic desire to nab the royals rather than the prostitution pawns. He wanted a more direct link to Luciano himself. He needn’t have worried too much, for, shaken by raids and leaks, Luciano cautiously left New York – but was ultimately arrested, as was the notorious Tommy the Bull. Informants aided Eunice, and, after all the power moves, machinations and intimidation, Lucky Luciano was doomed by prostitutes. And who knew this vulnerability all along? Eunice Carter.

In the 1936 conspiracy trial Dewey managed to get several incriminating confessions, none of them about the prostitution game. Regardless, Luciano got 30 to 50 after conviction. A decade later, Dewey agreed to commute Luciano’s prison sentence in exchange for deportation.

What amuses me about Luciano’s rise-and-fall story are the contrasted entwined fates of both gangster and lawyer. On one hand, Luciano’s persona was a mask veiling mere devilry:

In films and literature, Luciano is often romanticized. The reality was different. Luciano was brutally and violently ambitious. Even as a young up-and-comer he was, in the words of one biographer, “a killer,” a gunman whose dirty deeds were undertaken in darkness. As the boss, he was ruthless.

On the other hand, Eunice’s outer strength matched her inner integrity, and one might think of her as being destined to ruin Luciano since childhood. By novel-neat coincidence, in 1907, the same year the Eunice and her parents relocated to Brooklyn, a Salvatore “Charley” Luciana and his family moved from Italy to New York City, while, as Carter puts it, “across the East River, the black woman who would become his nemesis was also in grade school.”

Upbringing often aids destiny, which was the case for young Eunice. Her mother, Addie, worked as a teacher, editor and journalist. Restless after many years in a lousy marriage, she took the kids and emigrated to Strasberg. Then she attended Kaiser Wilhelm University, studying philosophy, and later joined the colored division of the YMCA to serve troops in France during World War I. Ever the accomplisher, as her daughter would grow up to be, Addie went on to co-author Two Colored Women with the American Expeditionary Forces with a Kathryn Magnolia Johnson. She also befriended NAACP chair Mary White Ovington and eventually participated in the Second Pan-African Congress with none other than W.E.B. DuBois. Years down the line Addie penned a biography about her first husband, William, called William Alphaeus Hunton: A Pioneer Prophet of Young Men. (Their son had been named Alphaeus, after William’s middle name, by the way.)

After graduation from Smith College in 1921, Eunice took up teaching, social work and writing, doing her part in contributing to the grand efflorescence of the Harlem Renaissance. In Harlem she met and married dentist Lisle Carter, and then she enrolled in Fordham Law School. When her political life bloomed, Eunice established herself as a lifelong Republican. “Although this attitude must nowadays seem quaint, in the context of the era it was by no means unreasonable,” writes Carter, who a little later explains that “her entire life experience had been of a Democratic Party in implacable opposition to the rights of her people.” Perhaps much of her Republicanism stemmed from her father, who “held that the Negro race would accomplish wondrous things if the white race would only leave it alone.”

Eunice lived in an era in which Tammany Hall made vehement pushes for white-vote supremacy, which bolstered her support for the GOP over the racist Dixiecratic Party back then. A darling of black journalists, “Eunice was by now one of the best-known Negro women in the country, and certainly one of the best-known Negroes in the Republican Party.” By 1940 she wrote “Taking Stock of the Negro in America in 1940” for the Colored Republican League of Maryland, and she said of Democrats: “We cannot in good conscience support a party whose controlling factors and guiding spirit fail to recognize that all men are created equal.” Eunice also opposed President FDR and was anti-New Deal, though she was a friend to First Lady Eleanor. Curiously, she campaigned for no Republican in 1936. Carter surmises:

Most likely, she decided to skip this year’s contest because she was too busy in the Prosecutor’s office, not because she had any doubts about the GOP. But given the racial controversy at the Republican Convention, Eunice was probably happy that she went to her reunion instead.

In local politics a year before that, the Republican Party sought a black opponent to incumbent Democrat James Stephens, and it chose Eunice for inclusion in the state assembly. “Yes, she was likely to prove a sacrificial lamb,” Carter writes, “but the party was delighted to have her aboard.”

Carter also focuses on the ratification of the Genocide Convention in 1950 (which wasn’t adopted until 1986): “[F]or all of its virtues, [it] was carefully drafted to let Iron Curtain governments off the hook…Opponents argued that the Genocide Convention had been created to allow to rest of the world to chastise the West.” Tempering equation of Jim Crow violence against blacks and mass genocide, Eunice declared that “the lynching of an individual or of several individuals has no relation to the extinction of masses of peoples because of race, religion, or political belief.”

After reading the above passage, my mind went to a pertinent exchange involving husband Lemaster and wife Julia in New England White. “We are avenging a far larger crime, Jules,” says Lemaster. “Remember that.” The narration reveals Julia’s private reaction: “Now she knew what frightened her. The confidence she had long admired in him, even when it swelled into pride, was really the zeal of the ideologue.” Another character, Mary Mallard, asks: “Do you really think America is evil?” “No,” replies Lemaster. “I think America has a short attention span.” This makes me recall something James Baldwin said in a 1964 essay called “The White Problem”: “What I am trying to say is that the crime is not the most important thing here. What makes our situation serious is that we have spent so many generations pretending that it did not happen.”

Similar to Baldwin, Carter exposes the blighting sins of slavery and its evil legacy, yet he has a wiser perception about long history, morphing mores, societal complexity, and both historians’ and history reviewers’ need for relativism. “It is the curse of historians, as the estimable Gordon Wood pointed out in gentler language, to judge the past by the norms of the present,” Carter declares in Invisible’s introduction. “Here I will try my best not to do that.” I needn’t stress that Carter is a scholar, but I do stress that he avoids the myopia of many addressers of race, instead bolstering his observations with similar substance and nuance as Baldwin, who didn’t throw all of America out with the bloody bathwater (just as he astutely rejected the bitter racialist rejection of Shakespeare).

Back at the beginning of her legal career, working as a lawyer in the women’s courts, Eunice found herself “stuck in a tawdry, professional graveyard from which few female lawyers returned.” Carter makes it clear that his grandmother faced the frustration of having her talents either underestimated or wasted throughout her career, though her career was by no means meager or futile.

After a race-charged riot in Harlem in 1935, Mayor LaGuardia established a Commission in Conditions in Harlem and appointed Eunice among other prominent black figures, such as A. Philip Randolph and Hubert Delany, or “the cream of Harlem sassiety,” as Carter cutely phrases it. Two years later a huge numbers operation co-run by gangster Alexander Pompez was in the law’s crosshairs, much to the public’s annoyance: “Harlem was rooting for the fugitive – and against those who were chasing him.” Public opinion turned against Eunice, but she marched on, remaining dedicated to Thomas Dewey, who won the position of New York County district attorney. Dewey indicted Tammany-empowered Democratic leader and crook Jimmy Hines for his association with Dutch Schultz. This led to a trial in which Pompez agreed to testify against Hines, a trial that became a mistrial before an eventual retrial with conviction.

Throughout Invisible Carter makes it clear that Eunice, who “never slept” and “lived on coffee,” was not only professionally relentless, but relentlessly loyal as well. One easily gets the impression that Dewey was both a boon and a bust for his protégé. Carter himself comes out and says it: “Eunice was not really suited to the life of jostling constantly for position of the Pyramid. Loyalty was once more her curse…”

She supported Dewey’s run for governor, which failed, and it seems the thanks he gave her was appointing someone else as a judge in the City Court. Eunice also was skipped over in Dewey’s choice of Secretary of Labor. Later she lost a delegate appointment. Dewey ran for President, hoping for mass Negro support via his civil-rights platform, but he lost again when a majority of Jim Crowers kept FDR in the White House yet again. (Democrat opposition claimed that Dewey was a candidate of division.) Failure struck Dewey again when he challenged Harry Truman in 1948. The Negro vote, unstable due to matters seen as civil-rights neglect, went mostly Democrat. As if symbolic of the changing tide, Eunice didn’t even make the Pittsburgh Courier’s honorable black-women list!

Now, in this biography there’s a lot written about Eunice’s brother Alphaeus, whom the FBI surveilled and kept files on, and it’s no stretch of credulity to wonder if his personality and politics helped his sister win some losses. Odiously fanatical, his troubled/troublemaking type reminding me of, say, Doctor Zhivago’s Pasha, Joshua in Jason’s Lyric, or any of Dostoyevsky’s annoying socialist hotheads, Alphaeus was a lightning rod for controversy, chasing Utopia obstinately – and deafly toward Eunice’s social standing. “Although her career would in some ways continue to thrive,” writes Carter, “she would go to her grave believing that her brother’s wild politics had stalled her rise in the district attorney’s office and wrecked her lifelong dream of becoming a judge.” Carter addresses the ambiguity of whether or not Alphaeus cursed Eunice, so to speak:

Not a scrap of paper suggests that she shared her brother’s views or participated in his activities. But part of the danger of Hoover’s files was that whether you had been exonerated was less important than whether your name appeared. There is no way to measure the effect of Alphaeus’s avowed communism on his sister’s career. Eunice always insisted that the effect had been enormous. It would fly in the face of history to suppose that the effect had been zero.

Rather than blaming the bigger picture of the so-called Red Scare (which was fueled by both fact and hysteria), “she always blamed Alphaeus.” But, to be fair, Alphaeus didn’t give a damn about how his radicalism blew back on his sister’s career. At the end of 1951’s Dennis v. United States eleven Communist Party culprits were sentenced, including Alphaeus. And guess who else was associated with all the Red hubbub? Author Dashiell Hammett (whose work I appreciate, but whose wisdom seems shallow, if not non-existent). Alphaeus didn’t have isolated, lowly elbows; they rubbed with some great names, such as friendly W.E.B. Du Bois and Paul Robeson (who was famously/infamously delighted with the Soviet Union).

The door slammed shut not only on Alphaeus’ problematic antics, but also on Eunice’s viability. As Carter writes, “once Alphaeus went to prison – and given what he went to prison for – Eunice knew that her own career as a public figure in the United States was over.” I’m reminded of Orson Welles never quite being able to repeat the trusting admiration produced by his precocious artistry in Citizen Kane in the 1930s until his death in the 1980s. In a way, Eunice’s having been “the Black Woman Lawyer Who Took Down America’s Most Powerful Mobster” was her Kane. My heart went out to her as I read on that “she felt the rest of her dreams, and even her public persona, slipping away.”

Alphaeus was eventually let out of prison, having not been visited by his sister even once. Eunice had repudiated him completely, apparently, for Carter says that the two “never spoke again.” In Invisible’s epilogue we learn that Alphaeus’ reputation was ruined in America, so he gave up and moved to Ghana, taking over W.E.B. Du Bois’ Encyclopedia Africana before fleeing to Zambia with his wife in the 1966 coup.

As for Eunice Hunton Carter, the woman with so much potential and drive who was rendered impotent in so many situations and driven to resignation to the fact that favored (and even mediocre) folks tend to win accolades and authority, she did not obtain the judgeship she desired. As far as I can tell, this is an injustice. Surely, Eunice was born to be a judge or something as prominent. Stephen Carter, her compassionate and remarkably objective (despite his descendency) grandson and biographer, acknowledges that her ambitions were probably extreme and therefore effected a bitterer anticlimax when they were thwarted. But he balances that possibility with a hard question: “We must ask ourselves whether if Eunice had been white and male and had the same resume, she would not have gone further in her career.”

In 1944 the great Frank Capra put out a military/flag-waving documentary called The Negro Soldier, and, against his wishes, scenes depicting Negro agency were omitted to avoid whites’ offense. Such overt omission seems unlikely and even unimaginable these days, but it was part of a systemic (dare I say pathological?) norm. Carter goes back almost forty years and says of a white riot against blacks that resulted in maybe over a hundred deaths and the destruction of much black-owned property, pointing out that though many whites were taken into police custody in the aftermath, “most of those arrested were black men with guns, trying to protect their homes and businesses” and “the overriding fear was of marauding Negroes with guns.” For all of America’s justifiable reverence for the sanctity of the Second Amendment, there was – and is – a double-standard about self-defense by certain people – which was a fundamental issue on which Malcolm X and, later, the provocative but poignant Black Panthers, zeroed in.

“Politics then were like politics now,” writes Carter, adding for example that regular police presence in Harlem irritated rather than consoled black residents back in the day, as it often does nowadays. “There is something terrifying in the realization that the needs of the darker nation in the 1930s were little different from the needs of the darker nation now,” Carter observes, “but it is nevertheless a fact.” However, his good-historian wisdom (and consensus-wary, truly intellectual thinking) rather than a mere myopic judge from the “superior” present gives him perspectival astuteness (and maturity). This shows in his placement of Eunice’s obstacles and race relations today in realistic context:

Today the situation of the darker nation is enormously better than it was in the days when Alphaeus and Eunice crashed against the wall of race. To insist, as some still do, that nothing has changed is an act of willful ignorance – and an insult to the generations who have beaten at that wall.

Yes, much has changed, and much has continued openly or has been corrosively sublimated, and to deny both grand transcendence and grim atavism is foolish. But in spite of the two-steps-forward-three-steps-back nature of race relations and basic human respect, I do think it may be time to blur – if not remove – the lines of so-called Black History in order to obliterate relegation of folks such as Eunice Hunton Carter to segregated bookshelves. As I remind people every February, every month is “Black History Month.” James Baldwin put it better in an answer he gave during a House Select Committee in 1969: “It is our common history. My history is also yours.”

One thing Eunice was not a First in was living a life of deferred and deterred dreams, for whatever reason. Nevertheless, she helped make the “darker nation” better. And, thanks to her biographizing grandson’s Invisible: The Forgotten Story of the Black Woman Lawyer Who Took Down America’s Most Powerful Mobster, she is neither invisible nor forgotten.

by David Herrle