Rating: ❤❤❤❤❤

They loved each other because everything around them willed it, the trees and the clouds and the sky over their heads and the earth under their feet. – Doctor Zhivago

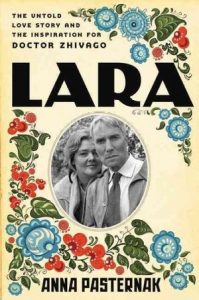

Lara Antipova and Yuri Zhivago are among my favorite fictional lovers (such as Gone with the Wind’s Scarlet and Rhett, and Cheers’ Diane and Sam), and Olga Ivinskaya and Boris Pasternak are two of my favorite real-life lovers (up there with Liz Taylor and Richard Burton, and Cleopatra and Mark Anthony – coincidentally enough). That is, Olga and Boris became lover favorites only recently, after reading Lara: The Untold Love Story and the Inspiration for Doctor Zhivago by Anna Pasternak, Boris’ great-niece and author of Princess in Love and Daisy Dooley Does Divorce. Regardless of societal distaste for non-monogamous infidelity, I must admit that I find deep appeal in the requisite adultery of the original courtly-love tradition and the vibes of that tradition in this particular romance.

For instance, how could I ever resist how Boris put his attraction to Olga in words? A passage from his personal writings illustrates the hardy, no-frills radiance of his beloved:

She has no coquetry. She does not wish to please or to look beautiful. She despises all that side of a woman’s life. It’s as though she were punishing herself for being lovely. But this proud hostility to herself makes her more attractive than ever.

A tamer rendition of this praise appears in Doctor Zhivago, when Yuri spots Lara in a library: “She despises all that aspect of a woman’s nature; it’s as though she were punishing herself for being lovely. But this proud hostility to herself makes her two times more irresistible.” Really, Lara and Yuri are Olga and Boris.

What makes Lara quite special is its revelation and expansion of the deep extramarital romance between the famous Russian writer and his extraordinary, Muse-caliber mistress. And, most important, the book elevates Olga way above the negatively connotative “mistress” term, giving her not only flesh and blood but mind and spirit as well. Anna accomplished this despite long repression by revisionist Pasternak descendants who attempted to keep the Olga connection from being popularly known since, as Anna puts it, “a public mistress was indigestible to their staunch moral code.”

The bottom line is that the novel Doctor Zhivago, a classic since the first day of its publication, a work the envious Nabokov called “a sorry thing” and “clumsy, trite and melodramatic”, owes its existence to the existence of Boris’ “Olia,” his “white marvel” – just as Olga’s “Boria” owes his literary fame – and life, probably – to her. Olga factored so much that, with novelistic irony, the obtuse KGB accused her of being Zhivago’s secret author, citing Pasternak’s handwritten dedication in her copy of the book, which read, “It was you who did it, Oliusha! Nobody knows that it was you who did it all – you guided my hand and stood behind me, all of it I owe to you.”

Boris wrote Zhivago, for sure, but besides inspiring the love story and supporting Boris beyond all expectations, Olga also served as editor and retyped the manuscript twice. As if in the novel herself, she also endured imprisonment and hard labor for Boris’ sake, using her natural resilience and unshakable belief in the novel’s destiny to strive on. This passage from Lara is both a perfect assessment of Olga and the biography’s central reverence:

…Olga could hardly have given more of herself, in supporting, loving and encouraging the tortured writer. From the tremendous amount of effort that Olga offered to the creation of Doctor Zhivago, she derived almost as much satisfaction as if she had written the novel herself. She was generous to the core in assisting her beloved to fulfil [sic] his literary dream.

Both faced persecution by the puritanical, censorious Communist government, but Olga’s toll was much harsher than that of her dear poet. This disparity of suffering prompted Anna to worry about the nature of the couple’s relationship:

When I began Lara, I was secretly concerned that I would discover that Boris used Olga. As I dug deeper into the story, I was relieved to find that this was far from the case…I believe the depth and passion of his ardour [sic] differed from anything he felt for either of his wives. Not just out of gratitude that Olga risked her life in loving and standing by him. But because she understood him; she had a deep inner knowing that in order for him to find a resting place of fulfilment [sic] within himself, he needed to write Doctor Zhivago…

Of course this would be a natural worry for most fans of heroes of one type or another. How much more the worry must be for a relatively proximate descendant. Nonetheless, Anna plumbed her great-uncle’s biography with integrity and bravery, putting together this real-world parallel Doctor Zhivago universe as a result.

Having difficulty thinking of Boris Pasternak as a poet more than a novelist, as he’s revered in Russia, is understandable, but anyone familiar with Zhivago realizes that it’s a poet’s novel, complete with a virtuosic show in the form of an appended collection of Yuri’s poems. However, for a long time Boris had had a serious desire to write a novel on par with Charles Dickens, whom he didn’t think he could ever rival; and though My Sister, Life, his famous poetry collection, was a critical success, Boris’ single great novel compelled him more than anything else.

If there’s anything truly miraculous about the composition of Doctor Zhivago, it’s that it was ever completed in and circulated beyond Stalinist Russia. Following brief hope when czarism fell, Boris became disillusioned with the atrocious Bolshevik Revolution and its ensuing collectivization, describing the mess as “bloody, pitiless, elemental, the soldiers’ revolution, led by the professionals, the Bolsheviks.” This disillusionment is expressed by Zhivago’s Nikolai Nikolaievich, who says, “[W]hat for centuries raised man above the beast is not the cudgel but an inward music: the irresistible power of unarmed truth.” Stalin’s regime certainly didn’t value truth if it failed to serve its self-empowering ends, so the core spirit of Boris’ novel could be interpreted by the regime as nothing but disloyal and corrosive. An anti-opiate for the masses, if you will.

Over the years of mounting misery and paranoia in Soviet Russia, Stalin executed right-hand men and real or perceived enemies of the state alike, but Boris, who wore his individualistic personality on his sleeve, who wrote a book containing blatant anti-Marxist sentiments, and described Bolshevism as “pathetically amateurish” and senseless to the enlightened likes of his Yuri and Lara characters, not only survived purgation but ended up a Nobel Prize nominee. Yet, the miraculousness came with a cost. Employing a typical mobster technique, Stalin punished Boris indirectly by punishing Olga directly via two labor-camp sentences by which “precious years of her life stolen from her due to her relationship with Pasternak.”

Throughout Lara Anna reiterates the unequal “moral fortitude” of the lovers. Boris’ fundamental failing comes down to this embarrassing fact: “he did not save her.” This can be blamed on his eclipsing ambition, his near-myopic drive to realize beautiful, sane Zhivago in the midst of ugly madness. Boris wanted nothing more than to be recognized for his literature, to shine beyond his relatively menial translation career. As pressure from the regime increased, he believed his book doomed to obscurity, predicting that “they will not publish this novel for anything in the world…I do not believe it will ever appear in print.” “Ideas are not born to be smothered at birth,” he once wrote to his publisher, “but to be communicated to others.” Though no publication at all frightened him, the prospect of Zhivago getting its due attention after his death provided no consolation, something expressed in the following passage:

His friend Ariadna Efron once noted that Boris “had the vanity of any man of true talent who, knowing he will not live to see himself acknowledged by his contemporaries, and hence snapping his fingers at them for their failure to understand him, nevertheless craves their recognition more than any other – he knows perfectly well that the posthumous fame of which he is assured is about as much use to him as a wage paid to a worker after his death.”

Notwithstanding his failure to spare Olga the punishment meant for him, Boris contradictorily displayed a martyr-like adamancy when it came to defending his work and resisting compromise with the soulless bureaucracy that sought to undermine or appropriate him. For example, after Stalin’s second wife, Nadezhda, killed herself, Boris refused to sign a sympathetic letter offered by prominent Russian writers. He also defied the Writers’ Union and declined to support the execution of several espionage-charged military men, explaining his abstinence to Stalin as an unworthiness “to sit in judgment over the life and death of others.” Luckily for Boris, his signature ended up being faked in the Literaturnaya Gazeta, which spared him from brutal reprisal.

Olga lacked such fortune, as we know. In the fall of 1949 she was arrested by the MGB (the KGB’s precursor), incarcerated, and later interrogated about her lover’s political sympathies. As if the abuse in prison wasn’t enough, she miscarried the baby that she’d conceived with Boris before her incarceration. After several months she was transferred to a labor camp in Potma for a grueling and merciless five-year sentence. The following excerpt from Lara further emphasizes the novelistic nature of this true story:

As she worked, Olga’s head was alive with Boris…He was injected ‘like dye’ into her nervous system; so consumed was she with thoughts of him. To keep her mind agile – and to ward off insanity, or a complete mental breakdown – she memorized his poems along with poems that she had composed all day in her mind.

After all that, the aforementioned lesser “moral fortitude” is evident in Boris’s decision to cut off the relationship after he got word of Olga’s early release in the wake of Stalin’s death in 1953. However, the two reunited once she came back. Olga conceived with Boris again, but, sadly, the child was stillborn. The 433-page manuscript for Doctor Zhivago lived on, however. A publication offer came to Boris from an agent for Italian publisher Feltrinelli Editore, Sergio D’Angelo (who reaped $450,000 for the film rights years later). More cautious, perhaps because of her dreadful experiences, Olga was quite displeased and frightened by this development, and a note informing her that the Writers’ Union and the Culture Department of the Central Committee of the Communist Party had gotten wind of the manuscript’s circulation outside of Russia confirmed her misgivings. The pair had attracted the KGB’s dangerous attention once again.

Soviet suppressors kicked into high gear, denouncing the manuscript as counterrevolutionary, and they raged like hell to get it back from Feltrinelli Editore before publication, as well as a further problem: the optics of other countries publishing uncensored editions of Zhivago while Russia released a version with glaring expurgations. The Culture Department head, Dmitri Polikarpov, urged Olga to somehow retrieve the manuscript, but the publisher refused to cooperate. As for Boris, the bravery he tended to exhibit for his art also kicked into high gear:

It’s an important work, a book of enormous, universal importance whose destiny cannot be subordinated to my own destiny, or to any question of my well-being. As existence and publication, where that is possible, are more important and dearer to me than my own existence.

Though Boris refused to sign a prewritten letter of request for the manuscript’s return from Feltrinelli, D’Angelo convinced him to comply for the sake of appeasement and since Feltrinelli wouldn’t budge anyway. Doctor Zhivago was published in Italy, becoming an instant bestseller and beating Nabokov’s wildly popular Lolita in America by 1952. In its counterpropaganda efforts, the CIA even weaponized a Russian translation via the Bedford Publishing Company, and the Soviet Union’s black market abounded with expensive illegal copies of the novel after a Russian edition was printed and distributed strategically. For years Boris was nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature, once by Albert Camus in 1957, and he finally won in 1958. Polikarpov, backed by the Soviet machine, urged Boris to decline the prize. In response, Boris composed a twenty-two point letter for the complicit Writers’ Union, refusing declination and presenting a rather bold ultimatum: “I do not expect justice from you. You may have me shot, or expelled from this country or do anything you like.” Unsurprisingly, the Writer’s Union expelled him and the KGB surveilled both Boris and Olga, compounding the pressure that ended up causing Boris to renounce the prize via a telegram to the Academy. When exile of Boris became a serious prospect, Olga appealed to Nikita Khrushchev to allow him to remain in Russia. But self-denunciation before the Soviet people was demanded, which, of course, an infuriated Boris rejected.

As his health worsened in 1960, 70-year-old Boris signed over his power of attorney and literary work to Olga, not his wife Zinaida. Incensed by having been forbidden from going to Boris when he had a heart attack and his lung cancer became critical, Olga resolved to desperately fight her way into his house and run to his bedroom after she learned of his death. Not only was she shunned by the Pasternak family, but Khrushchev’s machine chose to use her for revenge against the dead writer. In spite of Sergio D’Angelo’s attempt to help from England, Olga was put on trial along with her daughter Irina, and both of them were given gulag sentences. Eight years went to Olga and three to Irina, but Irina was released within one year and Olga served only four. She went on to live for a few more decades, writing of her romance with Boris in A Captive of Time in the late 1970s and living to see Boris’ Nobel Prize given to his son, Evgeny, in 1989. She passed away in 1995.

It’s funny how time changes perspectives and softens hearts. Something Anna mentions in the book reminds me of how Henry Kissinger ended up telling Coretta Scott King, “You all were right and we were wrong about Vietnam.” None other than Premier Khrushchev eventually felt shame for his role in suppressing Boris’s great novel:

Khruschev, who found time to read Doctor Zhivago in his retirement, said he regretted his treatment of Pasternak…and acknowledged that the decision to ban the novel in Russia and force Boris to renounce the Nobel Prize “left a bad aftertaste for a long time to come…”

Because of Doctor Zhivago Boris Pasternak shares a throne with the likes of Dostoyevsky, Victor Hugo, Melville, Ellison and Shakespeare, those magnitudinous creators of characters who embodied different ideas. The novel is truly destined to speak to the ages though it’s a deeply personal story originating from an individual’s individual. The personal and universal needn’t be mutually exclusive, however, for, as Boris wrote in his autobiographical Safe Conduct, “the more self-contained the individuality from which the life derives, the more collective, without any figurative speaking, is its story.”

And, thanks to Anna Pasternak, we know that the personal (and universal) story of Olga Ivinskaya “is one of unimaginable courage, loyalty, suffering, tragedy, drama and loss.” Though Anna describes her great-uncle Boris as “both hero and coward, genius and naïve fool, tortured neurotic and clinical strategist,” a man who did fail to save his true love from political mistreatment, there is no doubt that he adored and highly respected Olga to his dying day. A few lines from one of his letters to her during a painful illness say it all, as far as I’m concerned: “Thank you for an infinity of things. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you.”

Yes, Lara and Yuri are Olga and Boris indeed, as intended by the novel-writing poet. “And what is Doctor Zhivago, if not his long and heartfelt love letter to her?” asks Anna. I agree with my entire heart. Likewise, Anna’s Lara should be considered an affectionate love letter to them both.

– David Herrle