Lucy Pear. What a name.

– Leaving Lucy Pear

Rating: ❤❤❤❤

Fruitful Fiction

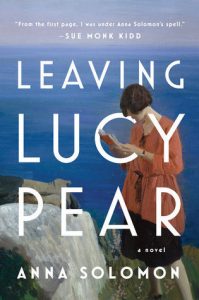

For many years I’ve drifted away from reading fiction, and I can muster the patience for it only occasionally. Whenever I do breach the front cover of a novel, I hope for linguistic grace, some psychological/philosophical sinews, literary depth and context, and at least one character for which to root. Thankfully, Penguin sent me Leaving Lucy Pear by Anna Solomon, former NPR journalist and author of The Little Bride. Not only does this book have my vote for Destined to Be the Next Merchant Ivory Film (if not just for the cover image: a detail from Laura Knight’s lovely Summertime, Cornwall), but it fulfilled my hopes and salved the friction I have with fiction, as well as presented a rather believable world presented by lush, poetic prose.

Though I hesitate to risk insult by comparing, Leaving Lucy Pear seems to share the same cloth as E.M. Forster’s Howards End, just about anything by Willa Cather, Virginia Woolf’s novels, particularly To the Lighthouse (which is mentioned and discussed in the book), and such. Also, the title character’s origin and later circumstances give the book the vibe of myth or fairy tale, innovating the familiar tradition of foundlings/orphans in literature: Moses, Oliver Twist, Jane Eyre, Paris of Troy, even Hans Christian Andersen’s Thumbelina and the tale of Briar Rose.

I fear no spoilage in nutshelling the book’s fundamental situation, much of which is given away on the inside of the dust jacket. Teenager Beatrice Haven reluctantly abandons her infant daughter in her Uncle Ira’s pear orchard, and Emma Murphy, an intrepid mother of eight children, raises the girl as if she were her own. The girl’s adopted name, Lucy Pear, is owed to where she was found, obviously, and one of Emma’s children’s innocent ideas: “Can we call it Pear?” Ten years later, in one of many striking coincidences, Emma comes to work for Lucy’s biological mother, now named Beatrice Cohn, and, of course, dramatic dominoes begin to fall from there. Knowing this doesn’t spoil the reading. What matters is how it’s told, and Anna Solomon tells the story with delightful lyrical care.

The story begins in 1917 Gloucester, Massachusetts, as young Bea sneaks down to the cellar of her uncle’s house with her shawl-swaddled infant in her arms. The vagueness of Bea’s surreptitious, desperate objective adds to the instantly established suspense, and there’s a soft weirdness to the opening pages, including a sort of sentience in the shovels and hoes presumably propped against the wall of the dark cellar, as described in this passage:

They had witnessed flood and fire…They had even, once upon a time, been in the presence of another unwed mother and her infant. Knowing this might have put Bea’s own suffering in perspective. But she did not know and she had not been taught perspective.

Once free of the house, Bea hurries among the pear trees of an orchard, and she ponders the trees’ quality Braffet pears and their importance to her uncle. Inanimate objects are personified again when Bea thinks of how Ira “talked about his pears all the time, as though they were the children he wished he’d had, braver and brighter than his own.” Aside from hinting at the negative aspects of Bea’s cousins who will be introduced many years later in the book, this line establishes the basic themes of children, pregnancy, fertility and parenthood that cry from the soil of Leaving Lucy Pear.

This personification/child metaphor arises again as far ahead as the seventeenth chapter, in which one of Bea’s visiting cousins, Oakes (who is a caricature of the stereotypical xenophobic/cartoon-capitalist bigot) mockingly regales the room with an amusing scene (only to him) he’d witnessed a month before: an Italian man removing a small tree from the ground, “a bundle, about the size of a child,” to nourish and then rebury it. “I think it’s sweet,” says his wife, Adeline. “It’s like his baby.” Her response follows Oakes’ disgusted wonder at why the man bothers to attend to “a tree that’s not even supposed to go here in the first place” – which brings us to an actual child (about the size of a bundle), Lucy Pear, and a woman, Emma Murphy, who assumes the noble responsibility of nurturer of a displaced life.

Emma and her children have been periodically stealing pears from the Hirsch orchard, so Bea timed her drop for what she guessed might be their next session, hoping that her baby would be discovered and taken with them. It’s either this or the Orphanage for Jewish Children, which would have accepted the newborn right away if not for Bea’s hesitation. But now, in spite of the agony of the decision, Bea wants to attempt a new, successful, stigma-free path in life. Besides, it’s hinted at and then overtly revealed that the baby’s conception is a result of rape by a then lieutenant William Seagrave, who is by 1927 a Navy admiral, ignorant that he left Bea pregnant a decade ago. His crime is to blame for Bea’s consequential underachievement and stunted adulthood. As the narration insightfully puts it, the rape “had been worse than anything Bea had ever feared, worse – she had the thought – than if he’d murdered her.” I applaud this notion because I consider rape a kind of murder, a spiritual murder that leaves victims alive to relive their souls’ deaths again and again.

Pitiful Bea leaves the baby at the base of a pear tree, the Murphy’s show up and Emma becomes the mother of Lucy Pear. Ten years later Emma recalls how her ability to breastfeed the foundling, since she’d nursed her youngest child, Janie, rather recently, solidified the bond and “opened up a hole in Emma, a new, bloody tunnel through her heart.”

The novel skips ahead to 1927, with a man named Josiah Story running the quarry of the Stanton Granite Company for his father-in-law, Caleb Stanton, and competing as a mayoral candidate against the Italian/socialist-leaning Frankie Fiumara, whose reputation is clouded by society’s collective association of him with two Italian anarchist agitators. This is where Solomon brings in her historical-fiction acumen, blending a sophisticated soap opera with actual sociopolitical events involving labor/business tension, Governor Alvan Fuller, Mother Jones, and the fates of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti (the aforementioned agitators). Unless it’s about time travel, I usually flee to the mountains from such specific history in stories, but the imaginary characters and action kept me at ground-level until the end.

For the sake of political strategy, Josiah seeks the endorsement of Beatrice Cohn (nee Haven), now an activist in the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. Meanwhile, he and Emma Murphy agree on a deal in which he provides capital for Emma’s fledgling business (production of perry, a fermented pear-based beverage, similar to cider) for thirty-percent of the profits. Not only does his immediate attraction bond him closer to Emma and result in a love affair, but he shrewdly kisses Bea’s ass by hiring Emma as caretaker for elderly Ira. This, of course, is the dramatic coincidence: two women of disparate lives are both mothers to ten-year-old Lucy Pear, and one of them, Emma, has the advantage of realizing the situation long before other does.

Emma also realizes that she’d encountered Bea years before, when a temperance group was proselytizing door to door and Bea insisted on leaving a prophylactic diaphragm with the ironic admonition to “at least deny [Emma’s husband] more children” if he didn’t sober up. Ill-tempered, disgruntled, odious secret-bearing Roland, the man of the Murphy house, alternately repels and attracts Emma. Not long into the service arrangement at the Hirsch estate, Emma’s former image of whoever Lucy’s real mother might be like is contradicted by evidence of a leisurely, seemingly sanitized life, and a slightly sadistic vengefulness – sharpened by a bit of reverse classism – swells in her:

But Beatrice was a rich Jew. Beatrice Cohn needed nothing…She had forgotten that she had once been desperate, that someone had saved her…[Emma] wanted to trouble Beatrice Cohn’s smooth exterior, poke holes in the myth of her goodness. She wanted to remind her.

No reminder is needed for Emma, however. She brims with regret for her past decision, suffers in the stagnant present and frets over the futile future. Her mother, Lillian, who pushed Bea into the arms of Seagrave back in the day, now urges her to start afresh by having a child with Bea’s husband, Albert, but guilt instills a binding, self-punitive mantra in Bea: “don’t want, don’t deserve.” Nothing allows her to forget what she’d done as a confused, afraid teenager. Not only does Emma have a lot of children, but Bea’s cousin-in-law, Adeline, has a young son and her other cousin-in-law, Brigitte, is pregnant by her cousin Julian. On top of that, Bea hasn’t been able to shake off the past attraction she and Julian shared back when they used to play piano together, before the lieutenant murdered her spirit nearly to death by rape.

Yes, Bea and Arthur could, technically, procreate and perhaps fulfill Lillian’s hopes of regeneration in her daughter, but Arthur is a closeted gay man who, in spite of sincere love and affection for Bea, believes that the marriage arrangement has run its course and he needs to live an authentic sexual and romantic life. Another possibility is recovery of Lucy, convincing her to return to her true mother’s arms, but there are too many obstacles, the most important of which being Lucy’s maturing agency.

Seesawing

The contrasts between Lucy Pear’s mothers are obvious but effective. Emma is unpretentious and hardy while Bea’s façade is flimsy and her emotional brokenness is barely concealed. Emma exhibits a tough pride while Bea is frail and paralyzed by feelings of failure, mediocrity and fraudulence. Emma has many children; Bea has none. Emma wants to specialize in production of an alcoholic drink (during Prohibition, no less), and Bea is a publicly respected teetotaler.

This seesawing applies to Josiah’s wife and lover too. Emma: “dry and rough” skin/Susannah: regularly uses moisturizing creams, Emma: amateur entrepreneur/Susannah: “a better businessman than [Josiah],” Emma: “soft stomach”/Susannah: slim abdomen, Emma: “anchored and hard”/Susannah: a quick swimmer, Emma: working class/Susanna: upper class, Emma: undeniably fertile/Susanna: miscarriages, childless.

Then there’s contrast between the orchard’s soft pears and the quarry’s granite stones, and between their physical attributes and methods of harvest. Of course, one can’t contemplate a pear without associating the general shape of a female body (especially a pregnant one) – and few can deny a pear’s abstract likeness to the scrotum. Furthering this metaphorical juxtaposition, I pluck a telling quotation from the book, when Josiah, smitten by Emma at first sight, inadvertently says, “Your eyes are the color of our stone…Olive green. Very rare. Very valuable. Almost no seams or knots.” I’m reminded of Ira marveling at his orchard’s fortunate yield of quality Braffet pears “blossoming like little gods.”

Favorite Parts Parts

There’s much bluster about the inadequacy and even audacity of men writing about women (a kind of “mansplaining,” to use the abused and abusive term), but there’s relatively little furor over women writing about men. If the sexes can be portrayed only by writers of respective sex, then it’s time to close down this art thing. The truth is that good writers can handle the task (read Memoirs of a Geisha for proof), and Anna Solomon excels at accurate capture of how typical straight men tend to emotionally and physically process attraction to women. For myself, I confess to actual sexual arousal at the overall portrayal of Emma Murphy, giving me special sympathy for conflicted Josiah, whose wife, Susannah, also is a physical treasure with “long, shiny hair,” “long, firm, blood-blood thighs” and “sharp, fine elbows.” Nothing more needs to be said to know how she looks.

Perhaps the most arousing phrase about Emma – the most arousing phrase in the book, really – is this: “her soft stomach, her strong hands, the calluses on her feet that brushed against him like sandpaper.” Then there are her insubstantial breasts, her unkempt hair, her cute overbite and “tall, pink gumline.” (Maybe Solomon has a thing for people’s gums; Bea’s gums – and Emma’s again – are mentioned elsewhere in the book.) Later, their affair in motion, Josiah regards Emma through the rearview mirror as he drives her to Bea’s home for the first time: “The straighter Emma sat, the harder her gaze as she refused to meet his eye, the more naked she became for him. She was like an animal he’d caught. He caressed the wheel and squirmed.” The central power in Emma’s candid, automatic beauty is her apparent unconsciousness of it, and, oddly enough, the following words about puberty-bound Lucy Pear also can describe unpretentious Emma: “Not so long ago, Lucy had had a child’s sense of her body, which is to say she was unaware of it as such. She moved, it moved, she was, it was.”

When Julian thinks of his passion for Bea while they accompanied each other on the piano back in the day, of all things he recalls the scent of her armpits (something about my wife that drives me wild), and he roots at the nape of his wife Brigitte’s neck to repel his own misgivings about her coming motherhood. I focus on this because I favor parts over wholes, including eroticized body parts over entire bodies. And the variety of bodies: Victoria’s Secret is only one of countless variations of individual ideal forms, to borrow from the novel: “short girls, tall girls, girls with small waists and large breasts or small breasts and large bottoms, all sorts of girls.” For this reason I appreciate Solomon’s apparent celebration of the fleshly core of love and desire. If Uncle Ira can gush over the appearance of a pear, why not lust for a lover’s earlobe, neck wrinkles, buttock freckle, ankles – or gums? This aesthetic atomization also applies to my approach to books (and all kinds of art). I enthuse over sentences, passages and certain characters more than so-called “unified” works. And my cherry-picking is as sensual as my erotic eye – and nostril.

The Writing

Anna Solomon must have a past of poetry writing. If not, she should try it, since her prose has so many gorgeous poetic moments (very shiny, pick-worthy cherries, if you will) – and she’s not even afraid to nonchalantly throw in a term such as “insouciance.” Some of my favorite examples follow:

Bea had never grown immune to her mother’s weeping. She had devised an expression, hard as a brick, that made her appear so, but inside she crumpled like a dropped puppet.

The forest floor looked made of fish skin, each leaf a glinting scale.

She tried not to look anywhere but the rug: its mute, whorling repetition. She felt the neat dents Adeline’s fingers had left in her arm, like little egg cups.

Her tongue was tired and thick, her mind slowed to a sweet, fractal mud…

His blood tried to leap up the creek, to fly out beyond the dock, over the river…

Sometimes the Solomonan borders on the Faulknerian:

Then Bea slipped past him, able to meet his eyes only for a fraction of a second, a bright, hot instant that stretched into her girlhood and down to her toes, and walked down to the point and out the granite bed of the breakwater where the noise of the house was far away and the water beat, hard enough between the stones to drown out the whistle buoy, seeing his long, angular face.

And Solomon’s talent for concise jabs of insight is evident in this passage involving pillow-talking Josiah and Emma: “Somehow the more sweet things Story told her about Susannah, the more unreal she became for Emma. She was a tale of a wife, a character.”

Leaving Lucy Pear is About Pairs

I confess that I feel similarly about Lucy Pear herself. I do like her, and her entrance and exit give the story dramatic symmetry, but I think the novel is less about the title character and more about the individuals connected with and by her, just as Saving Private Ryan (another verb/proper name title) isn’t really about Private Ryan and Twin Peaks is not Laura Palmer’s show.

As in myth, as in fairy tales, as in Dickens novels, Solomon’s foundling finds her way back to her origin, at first by gut feeling and later confirmed by sight alone. “Lucy knew – Lucy was not blind – that she was not a Murphy by blood” goes the narration. A desire to know what she knows swells in her. In Nobody’s Child journalist Kate Adie explores the worlds of orphans and expresses the common compulsion to learn of their birth parents in this line: “One child wrote from her pleasant new home: ‘I would give a hundred worlds like this if I could see my mother.'” Eventually, Lucy sees photo of Bea in a newspaper and then through a window of Uncle Ira’s house one night. The recognition is unmistakable, but the desire for long-term reunion doesn’t compel Lucy, however. Instead, she yearns to run away to Canada, where her older adoptive brother, Peter, lives. (I’ll leave her reasons to be found by readers themselves.)

I won’t go as far as to classify Lucy as a MacGuffin, but, for me, she’s more catalytic trope than, say Emma or Bea. I failed to attune to her wanderlust’s urgency, and I felt that her departure was a little too quick for me to get to know her. Perhaps that’s the point. Perhaps the novel also could very well be called Lucy Pear Leaving, or even, like a hastily written goodbye note: Leaving. – Lucy Pear. Emma wouldn’t want Lucy to end up struggling as she did or, worse, end up marrying a Roland, and Bea knows that the girl’s salvation lies in escape from there. I’m reminded of the mournfully self-deferred butler Stevens letting out a trapped bird from the house at the end of James Ivory’s heartbreaking Remains of the Day (based on Kazuo Ishiguro’s priceless novel): the unconscious vicariousness (plain to only viewers of the film) between that freed, soaring creature and Stevens’ museum-like, never-lived life.

Really, Leaving Lucy Pear is about – brace yourselves, and accept my apology in advance – mismatched pairs. There’s a general theme of loss or missed opportunity, of separation, of self-fulfilling miseries, but mostly the characters’ pairings are askew, even painful. A sense of misalignment and/or spiritual voidness haunts each one. Bea is adrift without Lucy; Lucy senses an otherness in her in spite of the inclusive love of (most of) the Murphy family; Lillian has shame for her Jewishness and shame for her shame; Julian is with Brigitte (who plays piano poorly) and not Bea (who has a pianist’s gift); Susannah wants nothing more than impossible motherhood while her husband’s lover seems to be able to conceive in the blink of an eye; Bea’s cousin Rose, an apparently liberated, non-monogamous, Freud-quoting woman, is unhappy with her single status, wondering if maybe marriage would be more suitable for her; creepy Oakes is husband to likable Adeline; Arthur (probably the most likable and conscientious character) is wed to Bea but wants to be with a man; Lucy is budding into a beautiful girl but she prefers boyishness in both action and appearance.

At the end of a scene in which Lillian rises to depart after trying to convince Bea to have another child, she notices a missing bookend at one end of a shelf and asks, “Where is the other one? Where is its friend?” Later in the novel, after Bea and Emma have tea together and things go sour, Bea spites Emma by snobbishly inquiring where she left the missing bookend while tidying the house by saying, “I hope you’ll put it back with its mate.”

– David Herrle