Rating: ❤❤❤❤

Born by Rape, Reborn by Rap

I can’t prove it, but I swear that I was the only white kid in my middle school who jammed Run-DMC and the Beastie Boys back in the King of Rock/Raising Hell/Licensed To Ill era (at least temporarily). In fact, I’m the one who introduced the groups to the only black kid in my grade. At home my crummy stereo was a sort of shrine, placed right below a huge Run-DMC poster on my bedroom wall. (Don’t hurl “cultural appropriation” at me. Via his Cyrano, Edmund Rostand was almost as much a pioneer of hip-hop as Kool Herc and The Last Poets.) Down the road Public Enemy, Grandmaster Flash, LL Cool J, Ice-T, N.W.A., KRS-One, A Tribe Called Quest, etc., were added to my repertoire.

Despite parental/church warnings about the soul-corroding effect of profane lyrics, I perceived further into the important musical art, sensing a sort of gunslinging cowboy/ronin/Robin Goodfellow (Puck)/Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog/folk-hero Anansi individualism and iconoclasm. Where many saw obnoxious braggadocio, I saw assertive samurai swords; where many heard glorification of sexism and crime, I heard Don Juan and Casanova, and the mythos of the Wild West, One Thousand and One Nights, feudal China and Japan, The Godfather and Scarface. Kurosawa meets Nietzsche meets Al Capone meets James Brown meets James Bond meets Huck Finn meets T’Challa – the egoism, the confidence, the aspiration and swagger of such music can be summed up in a line by Dostoyevsky’s Underground Man: “[A]ll of man’s purpose, it seems to me, really consists of nothing but proving to himself every moment that he is a man and not a piano stop!”

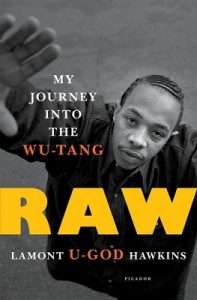

This notion is central to the life of Lamont “U-God” Hawkins of the Wu-Tang Clan, whose tale is told in his new autobiography, Raw: My Journey into the Wu-Tang. Though my first exposure to the group was via their debut album, their second album, Wu-Tang Forever, remains my favorite, if not just for the “Reunited” track. Wu-Tang always struck me as “heady,” street-wise and book smart, poetic and philosophical, sometimes too serious (a far cry from the occasional camp and frivolity of Run-DMC and the Beasties), real-deal badasses. So, when I noticed that U-God, an integral member of the Clan, had dropped a tell-all book, I was excited, needless to say. Having appreciated his Dopium and Venom solo albums, I was eager to read his longest lyrics ever, the story of his ascension from the projects into the Wu-Tang sky.

In an EXPLAIN! article Allah Mathematics said of the Clan’s Saga Continues album: “It’s a Wu-Tang record of course, but by now everybody that got the album know U-God is missing off the album. It can’t be a complete Wu-Tang Clan album without UG.” Quite a show of respect, one that reminds me of what Michael Palin said about the state of another brilliant, creative clan, Monty Python, after one of its key members, Graham Chapman, died: “Without Graham we’re not Python any longer. You can have variations of Python without Graham but it will not be what it was.”

Raw covers the rise of Wu-Tang and unflinchingly addresses the eventual ego/legal conflicts between U-God and RZA, but most of it focuses on the precarious origin and steady struggle of Lamont Hawkins himself. “I was a product of rape,” he writes. “I was a rape baby.” Though his father’s absence left a painful void in him, the nobility and bravery of his mother served as counterbalance. She opted against abortion because, as Hawkins says she claimed

God came to her in a dream and told her not to abort this child, that I was gonna grow up to be a great man someday, so she kept me. The dream solidified her spirituality, her connection with God.

Conceived via rape. There’s not a more negative beginning, is there? Yet time and time again folks have proven that even ill-gotten gifts of life are as precious as planned pregnancies – and a harvest of worthy fruit is given the chance to occur. Hawkins’ road to redemption and success wasn’t quick nor easy. “All the motherfuckers who went through hell growing up and got out of that shit don’t want none of it anymore,” he says near the end of the book. “They’re the ones who don’t talk about it; they’ve just left it behind, like it was in another life altogether.” Ironically, Raw does talk about “that shit,” and it shows that that shit remains in the present at least to some degree, no matter what.

Bone Men

Like comic books and jazz, the rap/hip-hop genre is quintessentially American, and New York City also is America in essence. Fittingly, Hawkins had a NYC childhood in Brooklyn and then in the Park Hill projects of Staten Island. Raw involves much about ghetto life and the criminal circles in which young Hawkins was immersed. He naturally ended up dealing drugs for quick, copious cash, but just as natural was a basic ethical spirit: “I still managed to keep my personal morals in an unrighteous setting. Even though I was doing wrong to get by, there were still lines I would not cross.” Later in the book he mentions his lifelong “respect for law and authority” and even praises Mayors Dinkins, Giuliani and Bloomberg for their parts in cleaning up the dangerous NYC subways.

This ambivalence between outlawry and order/self-control is strong throughout Raw. Above all, Hawkins seems to rejoice in what he considers a rough road to enlightenment, knowledge and wisdom, the proverbial steel forged in fire. “It fucked me up, and I’m never going to be the same…Because now I’m slashed,” he writes. The projects were beset by gangsters, and Hawkins participated in his share of gangs: the Baby Crash Crew (BCC), then Dick ‘Em Down (DMD), then Wreck Posse. Little did he know that this was preparation for his future inclusion in a gang of focused artists rather than aimless criminals.

The grim facts of carnality and violent impulse aren’t ever transcended fully, of course. “To this day, fists aren’t my last resort, they’re my first,” Hawkins admits. And he goes into a remarkable analysis of street violence, surprisingly castigating firearms as fundamentally cowardly: “The problem with a gun is that it’s a coward’s weapon, because anyone can use it.” Hand-to-hand combat was always preferable for him. Having been emulous of the great Bruce Lee, Hawkins says that “there is a science to fighting. Balance, technique, speed. Speed kills. Fuck what you heard. Fuck all that slow, I’ll knock you out, big dude shit. No. Speed kills.” Besides the 52 Hand Blocks, old-school street fighters knew “tae kwon do, monkey-style kung-fu, jeet kune do, and who knows what else.” However, true to that ambivalent nature I mentioned earlier, Hawkins reveals a gun-lust, so to speak, in this delightful passage:

But the baddest gun out there in Staten Island at the time was this chromed-out MAC-10. I shit you not, this gun was so pretty, it was like the Mona Lisa of automatic weapons…Everyone who saw it fell in love with it. It was the prettiest gun you’d ever seen in your life…It sounds weird that an instrument of death can be pretty, but that shit was beautiful, straight up…Just holding it, feeling that weight in your hands, made you feel invincible. It also made it really hard to get rid of.

With the popularization of crack, “straight butchery” became the neighborhood norm. Hawkins witnessed and became familiar with atrocity and mortality at an early age. For instance, his cousin Jimmy died of a heart attack and became a John Doe, until his corpse was found in the hospital morgue days later. Hawkins’ Hamlet-in-the-graveyard moment is perhaps my favorite passage in the book:

Once you see carnage and cadavers, the effect of life and death, somebody get shot in the face, all that shit, you change. Literally, you become a bone man. We’re all just bone men. We ain’t nobody. We’re so fragile. It’s crazy how people act so tough and hard and like they’re so invincible, when everything around us can kill us at any time.

I’m reminded of the lines in the Tao Te Ching about Heaven and Earth indiscriminately smiting us “like straw dogs.” Such perception fits neatly with the martial-art mentality adopted and innovated by the later Wu-Tang Clan. After all, their first album’s title is inspired by the kung-fu cult classic The 36th Chamber of Shaolin, a movie that both impacted my heart and broadened my mind with its presentation of the mindful body and the bodily mind, aside from its justice-pursuit trope. Shogun, ninja, samurai, dart guns – it’s no wonder GZA and RZA opened their “Liquid Swords” with a monologue clip from Shogun Assassin, and that RZA composed soundtracks for the Afro Samurai anime adapations.

Balancing that “dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return” mentality is the idea of inherent holiness accessible by Awakening, a la Gautama, Bodhidharma and, in a much different way, Jesus Christ. Hawkins speaks of divinely designed destiny, and how his discovery of the ways of the 5 Percent (or 5 Percenters) informed his worldview and helped in his self-discipline. He also credits this belief system as a salvational guide during his stints in prison. “Now, me being civilized man in jail, that’s what the Supreme Mathematics did for me,” he writes. “Being that I had knowledge of self, it kept me from being a Savage in pursuit of happiness.”

U is for Universal

As far as I understand it, the 5 Percenters claim divine superiority or godhood of “the Asiatic Blackman,” and that the Supreme Mathematics and Alphabet deliver adherents from their broken history, offering improvement and transcendence. “I Self Lord Asiatic master,” “for man is God and this is Self who is Allah,” “God that is I” and “Saviour (Self)” are several typical phrases involved. While notions such as “hell is the home of the ignorant, those who lack knowledge of self” are laudable, I tend to relegate numerology and such to a cool-but-ultimately-not-ultimate level of interest. And, aside from considering racial pride to be as problematic (and potentially evil) as racial shame, I’m suspicious of anything that seeks salvation via the self, just as I shun anything that raises another human being to savior status. Like Dostoyevsky and his mightiest apologist Berdyaev, I shudder at any iteration of Man-God. To put it simpler, if I’m my only hope, or if any of you are, then I’m fucking hopeless!

5 Percent stuff is mainly a Nation of Islam/Elijah Muhammad/Clarence 13X (of 120 Lessons fame) innovation (or hodgepodge) that, I think, problematizes or perverts Malcolm X’s post-Mecca epiphany of 1964, instead emphasizing the automatic societal devilry of Caucasians. It pops up here and there in Wu-Tang lyrics, such as in RZA’s spiel in “Reunited”: “Ruler Zig-Zag-Zig A Leg Leg Arm Head.” This refers to the Zig Zag Zig of the Supreme Alphabet, as well as the cipher of the name Allah: A for Arm = 72 degrees, L for Leg = 72 degrees, L for Leg = 72 degrees, A for Arm = 72 degrees and H for Head = 72 degrees.

In the Supreme Alphabet U stands for “universe,” or, as Hawkins writes in Raw, “universal.” Hence the u in U-God, a name given by a man named Dakim, Hawkins’ “enlightener.” “The majority of the world is the 85 percent,” Hawkins explains. “They are the deaf, dumb, and blind masses, basically Savages in pursuit of happiness…” “Bloodsuckers” and enslavers make up the 10 percent, while “the Poor Righteous Teaches” make up the remaining 5 Percent, who get a capital p. (Consult the lyrics of “Wu-Revolution” at the beginning of the Wu-Tang Forever album for a summarizing spiel on this stuff.)

What irks me about this “Poor Righteous Teachers” thing is Hawkins’ fundamentally contradictory worship of and constant grasping for wealth, which is plain as day in the following passage:

Let me tell you something about me; I love money more than I love anything in this goddamned world, except for my family and my babies. I love money more than I love drugs, women, all of that. I’m addicted to money I like to have it.

I do admire his honesty, but something about his pursuit of happiness via the “dolla dolla bill y’all” leaves a bad taste. (Of course, my distaste could be because I’m a relatively penniless peasant.) More than once Hawkins mentions the concept of C.R.E.A.M., which stands for “cash rules everything around me” (and later became a song), and he boils down the worth of wealth to this somewhat inarguable realization: “All I know is that as long as I got some money in my pocket, I can do whatever the fuck I wanna do.” Sure, with the 5 Percenters “the act of doing” and “power and refinement” are key values, but I’m wary of most self-aggrandizement, especially when it’s backed by hierarchical spirituality. However, Hawkins seems to believe for the sake of love, goodness and education, which is admirable, to say the least.

Another way to look at the whole money fetish is the apparent (unwitting or witting – or even unabashed) celebration of capitalism, excellence and achievement in rap/hip-hop tropes. In this spirit DidSheSayThat’s Sonnie Johnson has coined an acronym: WWHD, which is short for “What Would Hood/Hip-Hop/History Do?” “No rapper sings about wanting to live in Section 8 or having an EBT card,” she points out. Perhaps Hawkins’ later reiteration of the “I can do whatever the fuck I want to do” remark is more palatable for skeptical folks: “Being rich is having your bills paid off and being able to do the things you want to do when you want to do them.” I can’t argue with that. He’s right.

I find it amusingly ironic that in 2017 RZA said this to a billboard interviewer: “I will say for Wu-Tang, money wasn’t the motivation, it was artistic domination.” Perhaps this was true at the beginning, but Hawkins might say that the “artistic domination” was by RZA himself, something that led to the infamous 2016 lawsuit. By the time they were on tour with filthy-rich nominal socialists Rage Against the Machine, the Wu-Tang Clan were at peak success, and they were up to their chins in bread. Hawkins noticed a hesitation or unsureness in the face of fame and fortune:

I’m gonna tell you the truth here. I really think that at the time, some of my brothers were scared to make that kind of money. People say they want to make millions of dollars, but if you had a million dollars in your bank account right now, I bet you’d be scared to death…That has never been a problem with me. There’s a certain way you gotta move when you have that kind of bankroll. You have to approach your life differently.

Referring to the video for “C.R.E.A.M.”, Hawkins says, “It’s amazing how the song that depicts the harsh life in Park Hill is what ended up taking us out of that very same ghetto environment.”

Off the Charts

Back when Hawkins landed in prison, he tried to stay on track by attending both Narcotics Anonymous and anger management, as well as maintaining a strict routine and blocking out thoughts of the outside world, which made time seem to pass faster. Not long after getting out on parole he was tossed back into prison for another half year due to a technical drug violation. As fate would have it, “a nerd” named RZA, whom Hawkins got to know through mutual society, finally talked some sense into him. “God pulled me away from certain things and situations to save me,” writes Hawkins, “and this was one of them.” RZA’s outreach and artistic encouragement are what kept alive Hawkins’ basic appreciation for him even after their personal tension and legal conflict. Later in the book Hawkins says that he’ll “always have love for RZA. He really put my head back on my shoulders when it needed to be and pointed me in the right direction.”

By 1993, Hawkins replaced negativity with positive, creative action, and Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) was eventually signed by Loud/RCA. From there on much of Raw chronicles life on the road while touring, something I’ve never enjoyed reading about in any musician’s memoir, though some episodes made the effort worthwhile. After Hawkins’ astute presentation of his diverse observations, opinions and musings, the stuff about the evolution of the Wu-Tang is most interesting. In the same billboard interview mentioned earlier, RZA said that “the cool thing is that it started as a seed and it’s grown to a full-blossomed tree, and the tree hopefully will bear fruits and grow into an orchard.”

Orchards bear both good and bad fruit, but for much of the group’s heyday much good fruit was harvested. Foremost? The lyrics those dudes composed. The collected text could sell as a book that belongs among, say, the Chuang-Tzu, the Hagakure, The Unfettered Mind – even Buber’s I and Thou and Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra. Consider this spiel by Inspectah Deck, from “Triumph”:

I bomb atomically, Socrates’ philosophies and hypotheses,

Can’t define how I be dropping these mockeries,

Lyrically perform armed robbery,

Flee with the lottery, possibly they spotted me,

Battle-scarred Shogun, explosion when my pen hits tremendous,

Ultraviolet shine blind forensics,

I inspect you through the future see millennium,

Killa Beez sold fifty gold, sixty platinum,

Shackling the masses with drastic rap tactics,

Graphic displays melt the steel like blacksmiths,

Black Wu jackets, Queen Beez ease the guns in,

Rumble with patrolmen, tear gas laced the function,

Heads by the score take flight incite a war,

Chicks hit the floor, diehard fans demand more,

Behold the bold soldier, control the globe slowly,

Proceeds to blow, swinging swords like Shinobi,

Stomp grounds and pound footprints in solid rock,

Wu got it locked, performing live on your hottest block.

Of this Hawkins gushes in Raw:

Devastating. That shit was insane. He literally bombed the track. After you hear a verse like that, what the fuck do you do?…After you hear a verse like Deck spit on ‘Triumph,’ if you’re a true MC, you have to come better, or at least to the level he took you to…That was the thing about being in Wu-Tang when we were at our best. You’d hear a crazy verse, and you either try to top it, or come damn close.

Here’s what Hawkins/U-God followed up with:

Olympic torch flaming, we burn so sweet,

The thrill of victory, the agony of defeat,

We crush slow, flaming deluxe slow for

Judgment Day cometh, conquer, it’s war,

Allow us to escape Hell, globe spinning bomb,

Pocket full of shells out the sky Golden Arms,

Tunes spit the shitty Mortal Kombat sound,

The fake false step make the blood stain the ground,

A jungle junkie, vigilante tantrum,

A death kiss catwalk, squeeze another anthem,

Hold it for ransom, tranquilized with anaesthesias,

My orchestra, graceful, music ballerinas,

My music Sicily, rich California smell,

An axe kill adventure, paint a picture well,

I sing a song from Sing-Sing, sipping on ginseng,

Righteous wax chaperon, rotating ring kings.

I’d say that’s a crazy verse to match a crazy verse.

Before the Clan cohered Hawkins and Method Man collaborated musically while they worked at the Statue of Liberty and dealt drugs. The latter effort was not the exciting, anarchic adventure it’s often made out to be in shows and movies. According to Hawkins, “heartache and frustration” are the central elements of such entrepreneurism. “Full-time drug dealing is hard,” he writes. “Harder than regular working people can ever imagine.”

Method Man would later devise the W.U.-T.A.N.G. acronym: “Witty Unpredictable Talent And Natural Game,” and Hawkins honed his artistic skills via a daily writing routine. “A paragraph, a rhyme, whatever. You have to exercise your mind.” He attended college for a while before dropping out, but a superior class was in session. The Wu-Tang Clan formed: RZA = Mastermind, GZA = Genius, Inspectah Deck = Artist, Ghostface Killah = Storyteller, Masta Killa = Natural, Raekwon = Hustler, U-God = Ambassador, and Method Man and Ol’ Dirty Bastard (ODB) = (he doesn’t say).

Hawkins says that the Clan gelled into “a crew with similar upbringings and perspectives, but radically different ways of conveying their individual viewpoints,” which reminds me of something Terry Gilliam recalls about the advent of Monty Python: “Everyone was very individual and fighting for their stuff…and ideas seemed to be more important than individual egos in the early days.”

“GZA and RZA were like scientists with their rhymes,” writes Hawkins. “They read a lot and studied science and philosophy, and were just very learned individuals…My style is the project kid who was the real, actual street dude who fought against all odds to make it.”

Hawkins was repeatedly reminded of the fact of his being a “real, actual street dude,” even after he’d left the life. The worst was when the son he’d had at nineteen years of age, Dontae, was scooped up to be used a human shield in a shootout between two dudes. As a result, Dontae suffered hand and kidney wounds, which caused permanent damage that is dealt with to this day. Shattered, Hawkins retreated to drugs and booze, resuming the familiar negative spiral from years past. You’d think that the apparently tight Clan would circle the wagons, but

RZA and the others didn’t make it any better, ‘cause they didn’t give a fuck…I didn’t get any support from these dudes who I thought were my brothers. Matter of fact, they rubbed their fame and their wealth in my face even more. They made my life even fuckin’ rougher, much worse mentally.

“I lost myself,” he goes on. “I forgot who U-God – Lamont Jody Hawkins – was. So I went to the hood.” Basically, he lost his mind for a spell, which resulted in a two-week recovery in an asylum. Hawkins, as he puts it, “was off the charts.”

Meanwhile the Wu-Tang Clan was on the charts for quite a while. However, the surge waned, and typical creative and business frustrations poisoned the well. “It was no longer one for all and all for one,” Hawkins writes, expressing some resentment for RZA’s clampdown on control and his alleged increasing imperviousness to input and collaboration. “He forgot that you don’t tear down your soldiers,” he says, “you build your soldiers up.” He uses the recording of the Wu-Tang Forever as an example of RZA’s rivalry: “Several times when I’m on, RZA’s right behind me, like a fucking rhyme stalker or something.”

Before Hawkins tells yet more touring stories he gives a basic rundown of his suing of RZA and Divine for what he saw as mismanagement of royalties, business representation and branding. His characteristic ambivalence is probably never so strong as in this situation, for his loyalty to the Wu-Tang remains no matter what. The legal stuff is, quite frankly, business, and Hawkins is very plain about his financial shrewdness. Part of that is survival, and part of that is a sense of both pride and deserved profit from his worthy artistic contribution to the group.

Everything moves in arcs; entropy is the first rule of existence. Reading biographies, autobiographies and memoirs is always basically melancholic for me, for almost every one of them provides evidence of the rule. Once again, there’s a parallel with the Pythons. John Cleese’s description of their later (reluctant and strained) work together is applicable to groups in general:

One of the problems is that at the beginning of a group’s life they huddle together for warmth. Then as they go on and by and large prosper, they develop their styles and they don’t want so much to give up their own style in order to go back to a group style.

The popular phrase should be not be “from rags to riches” but “from riches to rags,” which is applicable to all ambitions, achievements, triumphs and Titanics. Even Wu-Tang won’t be forever forever.

“Time is a motherfucker,” Hawkins writes in his usual steely but lovely way at the beginning of Raw. “Time reveals shit. It wears things down. Breaks things. Crushes things. Kills things. Reveals truth. There’s nothing greater than Father Time.”

David Herrle