Rating: ❤❤❤

I stick out like a surreal thumb…

– Catherine, The Mismade Girl

Foxy Shades of Grey

Say the name “Sasha Grey” and chances are many men will either blush or pretend not to recognize it – or enthusiastically (usually tactlessly) express their approval for her skin-flick work. Though the instant association is warranted, given her status as a veteran pornographic icon, there are many more dimensions to Sasha Grey, and her fleshly excellence is matched by her intellectual and artistic skills. In my review of Bruce Dickinson’s memoir, I wrote the following:

Multitalented folks impress me in general…Several downright scholarly and highbrow famous eclectics/polymaths come to mind: James Franco, Sasha Grey, Eddie Izzard, Paul Robeson, Steve Martin, Sammy Davis Jr., Natalie Portman, Sophie Hunter, Viggo Mortensen, David Byrne, Sonic Youth’s Kim Gordon, Orson Welles, Ben Franklin – heck, Henry VIII.

Notice who’s mentioned between James Franco and Eddie Izzard. As far as I know, none of those other folks ever starred in X-rated videos (although one can never be sure about Ben Franklin), but Grey’s former career should be considered a feather in her curriculum-vitae cap, a rare plus rather than detraction. Without tumbling into controversial apologetics about the pros and cons of porn, I think Grey’s tenure in that industry (only a few years, believe it or not) has provided her with experiential depth, shrewd perception into human psychology and pretense, and substantive erotic/romantic authority.

Far from the popularly condemned unreality of pornography, I see in it an undeniable realness, a distillation of our dermal magnetism and our core insatiable, irrational sexual desire. It depicts the carnal frenzy during which, to borrow Sasha Grey’s words, “we’re not people anymore, just bodies,” the abandon that “reduces us to perfect purity of pleasure” and creates “the feeling of what happens when you become sensation and lose yourself completely inside your body.” Too few folks are honest about sexuality’s nitty-gritty, and such denial results in hang-ups, frustration and relationship-damaging frigidity. (Secular political correctness is as much to blame as prudish religions – maybe more.) To avoid such repression, Grey sought safe exploration of her sexual fantasies during those porno years, and it seems that her quest was successful.

Grey also proved herself as an actor, most notably in Steven Soderbergh’s The Girlfriend Experience, in which she played a stoic, almost android-like professional call girl. Then there are other cool gigs such as Entourage, Would You Rather? and Open Windows. (I recommend at least peeking at Indonesian goof-o-rama Pocong Mandi Goyang Pinggul.) On top of that, Grey is a model, a deejay, a photographer and, most important to this review, an author. Her apparent nymphomania is a sort of superpower which enabled her to strut into the erotic-literature world more than equipped to produce not only fiction but fucktion.

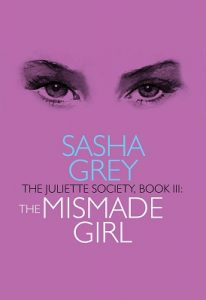

As I write this I’m listening to a tech-house mix by Sasha Grey at EARMILK, which, as much as I effing despise the term “ambience,” creates an ambience that is both lulling and arousing, cool but sweat-beaded, contemporary yet subtly atavistic. Besides being exactly how Sasha Grey strikes me, it’s the perfect way to attend to The Mismade Girl, the third and final volume in the author’s The Juliette Society trilogy.

I’m not sure if I bought the first book, The Juliette Society, years ago in order to rinse out the sappy taste of E.L. James’ pseudo-erotic/yawn-worthy softcore Fifty Shades of Gray, or out of intense curiosity to see what a book by such a gleefully savage sex savant would be like. After all, the book was named for and partly inspired by Marquis de Sade’s Juliette novel, which chronicles the depravity of the debaucherous sister of his Justine‘s virtuous title character. However, Grey’s intention wasn’t to only put merely porn to paper, but to mainly flesh out her protagonist, film-school student Catherine, whose first-person narration was very easy to take as the author’s actual voice.

Understanding that it’s sometimes unwise to conflate writing and writer, in this case (as in a good many cases) I think it’s mostly justified. Where things may seem fictional, they can be accepted as analogous and metaphorical, even confessional. To me, Catherine is an avatar of Sasha Grey herself. In a Hachette Book Group promo she described Catherine as her “alter-ego,” admitting that “she’s probably the person I would have become had I not chosen the path I took in life.” And in an interview with AXS:

As women, we are not raised to be strong, we are raised to be subservient. We are conditioned to be that way. I think it’s great when we can learn our way out of that. I wanted us, as an audience, to see Catherine go through that change and become more confident in herself.

Consider something Catherine said in the debut book: “It’s not as if I belong there. I’m a full-time third year college student. I major in film. I’m no one special.” Without revealing information that is better discovered while reading The Mismade Girl for yourselves, I will say that Catherine eventually achieves high-level status in The Juliette Society: quite far from her humble, naïve beginning. Not only does she cast off the yoke of shame, but she also comes to terms with “the occult nature of power.”

I parallel Catherine’s success with her author’s because Grey’s professional expansion beyond porn stardom burdened her with much to prove and perhaps more difficulty in proving it, though her networking and opportunity were certainly more bankable than that of the average ladder climber. “Now that I’ve seen success, I can’t just work on anything; I’ve got to make a statement,” says Catherine, expressing what must be Grey’s own conviction. “I need to prove to the naysayers and myself that my success wasn’t a fluke.” One must constantly maintain their relevance and artistic freshness – innovate interminably. Catherine again:

The hardest part of success isn’t achieving it. It’s trying to replicate it…The Godfather Part II, The Bride of Frankenstein, La Notte (though I’d argue that L’Eclisse was superior and the best of the trilogy). Hell, even The Empire Strikes Back and Terminator II were better than the first installations.

Thighs Wide Shut?

In the first novel of the trilogy, debutante Catherine plunges into a nebulous world, or, rather, the world plunges into nebulous Catherine. The Juliette Society is “like Fight Club, but with fucking,” so its thrill also can kill. Pleasure is mixed with danger; the hand that spanks also can strangle. Grey makes it plain that Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut is a major inspiration for TJS (think the film’s Saturnalia with buttplugs and dildoes added), and in The Mismade Girl her protagonist associates the costume sex party she’s attending with the infamous Hellfire Club (“as if we were Fellini’s audience”).

I call first-novel Catherine nebulous because, though she comes off as an acerbic, witty well-educated, ambitious person, she’s trying to find her way on limited information – and she’s in formation. The trilogy is about both Catherine’s and Sasha Grey’s awakening, and the pleasurable/painful development of figurative acuity. Even the books’ cover images imply this: The Juliette Society shows a coyly closed woman’s eye, The Janus Chamber shows two closed eyes, and The Mismade Girl shows two dominant open eyes. Via Catherine’s story Grey wants to provide other women an evolutionary model, encouragement of agency and shameless pursuit of sexual satisfaction. Though all women may not be as erotically immersed and diverse, I’m reminded of something former porn star Annie Sprinkle said: “Maybe there’s a little porn star in some of you out there and maybe not. But I can tell you from a whole lot of experience, there’s a lot of you in every porn star.”

Catherine eventually attempts to cultivate life outside of the Society, but by the second book, The Janus Chamber, having replaced her interest in the film industry with journalism, she developed an obsession with an impactful, hypersexy, enigmatic model so sonorously named Inana Luna, who was killed by mysterious means. This sucked Catherine back into the kinky, addictive world of the TJS, but her brave expose on Inana, published in defiance of the Society’s jealous privacy, caused her journalism career to blast off.

Inana continues to positively haunt Catherine and serve as both guide and goal in The Mismade Girl. “I’m thinking about what Inana’s journey was, and the way she dominated and submitted…,” says Catherine. “[I]t’s like Janus. Looking forward and back. Being on top looking down, and on the bottom looking up…” This is the fundamental tension Catherine always feels: the hardness and softness of one’s will, when to punch and when to take punches. “Let me be strong, let me be weak, don’t judge me for wanting what I want or sometimes for not knowing in the moment what that is until it happens,” she says. For instance, when Catherine meets an attractive man named Dominick, she decides to submit to him, to be gushing fruit in his dominant grip: “I want him to squeeze me and make me drip all over him,” she says, appreciating his role as aggressor, for “conquering instead of waiting for an invitation.” Isn’t this similar to what many high-powered jet-setters seek when they debase themselves in a sex dungeon: the release of steam at the end of a day of control and careful ego? (Perhaps this is why Catherine calls sex “the great equalizer.”)

Dominick reveals that a secretive philanthropist who calls himself Mr. X asked him to contact Catherine. X is a thriller-story trope: an international string-puller with bottomless pockets and a tentacular reach. He offers to facilitate an interview between Catherine and a Benny Arthur, former investment-firm partner of a Senator/one-time Presidential-hopeful Duncan, who’s been compromised by fraudulent schemes. Eager to validate herself further as a journalist, Catherine goes through with the interview, but, of course, “the hand that feeds you” lesson must be learned. Needless to say, Mr. X expects unquestioning cooperation, and, as in any familiar thriller, he turns out to have insidious plans that might or might not be thwarted by our horny heroine.

Another thriller trope, surprise appearances or returns of characters, pops up quite often in this trilogy, but once one accepts acute coincidences as part of Grey’s storytelling, they aren’t so jarring. For instance, one of Catherine’s former lovers, Penelope, a lovely woman who supported Catherine during her post-breakup grieving, enters the picture. (There’s also much about her other past same-sex lover: Anna.) Catherine admits that her Penny “lit up parts of me that I’d never felt before,” praising superior lesbian compatibility with fundamentally insatiable female genitalia: “It’s just orgasm after orgasm after orgasm until you – or both – passes out.” This alone should cause macho-minded men to shiver. There’s no competing with it, really. Also, Penny’s class status is aphrodisiacal:

…truly wealthy women have a certain scent, almost as though it’s a pure, clean powder, but also perfume…Maybe it’s more of an absence. The average person’s clothes absorb the scents of life along their day, especially anything they cook. Elite people hardly step foot inside a kitchen.

As much as Catherine pontificates about Western exploitation of poor countries, complacent tourism, the pretense of extreme wealth, the soullessness of corporations – and even the overestimation of “organic” food – throughout the book, her righteousness is belied by her suppressed desire for power and prestige. This basic betrayal of her professed values becomes important by the end of the book, if I interpret accurately. For all of its sexual liberation, TJS has a sinister side, which Catherine both resists and flirts with.

Intrigued by Mr. X’s second assignment, which requires her to fly to Honduras, Catherine comes into possession of Inana Luna’s diary once again. By the time Catherine and Mr. X finally meet in person it becomes obvious that X planned to entrap her for his sinister machinations from the start. I’ll not provide any more spoilers. Suffice it to say that Catherine’s reaction to knowledge of Mr. X’s evil plan is crucial to her own future as well as that of many others’.

In a sense, the trilogy’s twisty, intrigue-rich plot is a big Hitchcockian MacGuffin. What really matters is who Catherine is, was and will become. Again, the TJS series is about the maturation, enlightenment and empowerment (plus corruption?) of a woman. And this change is driven by sexual adventure and feeding of a bottomless carnal appetite. After all, as Catherine says, initiation has three stages: “Disorientation of the senses. Intoxication of the body. Orgiastic sex.” Emotional trauma also is a factor. It’s as if dissolution is necessary before a new cohesion. Similar to how Grey passed through the porn industry’s crucible, Catherine is melted down and reshaped by TJS. Catherine says as much:

I’m the Mismade Girl.

Like in the stage illusion, also called ‘The Mismade Girl’ – which, strangely enough, was partially devised and performed by Orson Welles – in which a woman climbs into a segmented box and is sawed in four…I’ve been completely taken apart.

Favorite Parts

I’m an atomistic aesthete. I prefer parts to wholes, passages to chapters, lines or stanzas to entire poems, movements to opuses, songs to albums – and so on. And this is why, honestly, I’m less interested in The Juliette Society trilogy’s plots than I am in Catherine’s digressions, which strike me as Sasha Grey’s sincere speculative opinions. Having extracted many passages from The Mismade Girl, I wish Grey herself would write a collection of essays featuring opinions on topics from film to cosmetics, from literature to science, from fame to fornication. Yes, the books are Catherine’s story, but I’m compelled to assume that the interspersed spiels are straight from the author’s worldview.

One minute Catherine’s spieling about fate: “Are we freed from the womb at our births only to be shackled by the invisible chains of destiny?” The next minute she’s musing over Rabelais’ Gargantua and Pantagruel, diving into the question of Rabelaisian authorship:

…the fifth book, which I’m not sure was actually written by Rabelais himself, or cobbled together from bits of first draft ideas and smoothing from the publisher, or if it was truly original material. There were some solid ideas in there, nonetheless. But it’s like the more controversial speeches by Hecate in Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Some of the language is different enough that there are some who say it had to have been penned by someone else and sandwiched in.

(Of course, this leads to some speculation on the Stratfordian/anti-Stratfodian controversy, but, as a mild Bardolater, I’m relieved by her preference for the Shakespeare-was-Shakespeare stance.)

More evidence of the ripeness for a book of Sasha Grey essays is the following passage from a mini-dissertation on kenopsia, the feeling one gets in empty places:

It’s one of those perfect words that capture a specific emotion so well it makes you want to grasp the meaning in both hands and never let it go because for that moment, you feel understood. Someone got how you were feeling so well they made a definition for it.

Even mosquitoes prompt digression about chance and purpose:

This inelegance of nature, the raw savagery of it makes me wonder how people can call it intelligently designed…and yet, the fragility of it all seems to give credence to that. You take one thing out and so much falls apart like a house of cards.

It’s why I don’t think humans will last forever. We’re much too destructive.

Also, I think all the opining on sexual stuff would be better in essay or article form rather than filtered through the mind and voice of a fictional person. Renaissance Woman Sasha Grey has expertise that is quite worth sharing directly, whether she’s giving women masturbation advice, composing play-by-play sexual fantasies or analyzing her own body’s responses to this or that stimulation.

The Picture of Victorian Grey

Consider these few lines from The Mismade Girl: “I can feel an orgasm building up inside like a goddamn symphony…it’s like holding back a tsunami.” “What’s sixty-nine plus sixty-nine plus sixty-nine?” “My pussy throbs. Hungry bitch.” (The “worst” that Grey can throw at us shouldn’t surprise or offend anyone who’s stuck with the three-volume story so far. After all, it’s not far into the first book that Catherine presents a treatise on semen.) Shameless female sexuality can be daunting for both females and males, especially males. As Catherine complains about falsely experimental men, “you want them to truly get kinky, and that’s when they get squeamish.” This reminds me of a scene in Kevin Smith’s Chasing Amy. “I was an experimental girl for Christ’s sake!” bisexual Amy says to her boyfriend Holden, who’s jealous of her promiscuous, explorative past. “Maybe you knew early on that your track was from point A to B, but unlike you I was not given a fucking map at birth, so I tried it all!” Such openness and frankness about sex and desire are immediately considered antithetical to fictional portrayals in the books of so-called more moralistic times, but I urge caution to anyone who may consider those novels and novels like Sasha Grey’s to be separated from by light years, even antithetical.

Now, surely this will seem ridiculous to many folks, but I associate Sasha Grey’s fiction to Victorian literature. Novels of that era dealt with science and religion, the past’s influence on the present, male and female social roles, courtship rituals, class delineation, the spectacle of fallen women, illness and recovery or death – and sudden or unlikely plot twists, coincidences and appearances or returns of many characters. All of these elements are strong in Grey’s books. One could say that TJS trilogy is a sort of inversion of Victorian fiction. In Moulding the Female Body in Victorian Fairy Tales and Sensation Novels (2007) Laurence Talairach-Vielmas observes that that era’s “rhetoric of feminine description aimed at erasing the female body,” which “annihilated the heroine’s physicality.” Grey’s neo-Victorian books emphasize the female body and elevate/almost sacralize the physicality of their heroine. Her heroine rises rather than falls. Also, a relish for sexuality underlay the stereotypical pretense of society way back then. In fact, I think the Victorians tended to have less sexual hang-ups than today’s political-correctness puritans.

As Camille Paglia puts it, “pornography is a pagan arena of beauty, vitality, and brutality, of the archaic vigor of nature.” There’s a unique glee in pornographic sex, a kind of mystical transcendence of mundanity, mores and stale cycles. “Safe sex is dangerous for relationships,” says Catherine/Sasha Grey. “Safe sex – by that, I mean the safety of predictability – kills. Routine kills.” I both nod and shake my head at this. I see both benefit and wretchedness in monogamy, in “settling down,” in scheduled spontaneity. I’m also careful to balance my enthusiasm for unbridled horniness and teeth-gritting pleasure with a reminder that the erotic is no more salvational than art is. Also, Grey’s sermonizing against shame seems to lack clarification, since I believe there’s a time and a place for some kinds of shame. Rabelais’ “Do What Thou Wilt,” adopted as the Hellfire Club’s credo, “frees” us so much that it imprisons us.

Remember the “we’re not people anymore, just bodies” phrase I cited early in this review? Well, besides during ecstatic sex this happens during illness and disease, and at the moment of death. “I don’t have a body,” Christopher Hitchens wrote while gradually dying of terminal cancer, “I am a body.” Life is movement, animation, flux, alternating pain and pleasure – all of which are heightened by sex. But sooner or later, motion zeroes out. As Catherine bluntly says, “At the end of the day, we’re all going to take that dirt nap.”

Far from deserving avoidance or repression, sex should be valued as a celebratory activity, a defiance of the Grim Reaper. I think sex is the most glorious bond humans can have, really. We’re naturally erotic, born hunters for sexual gratification. “We’re all freaks,” writes Grey. “In secret. Under the skin. In the sack. Behind closed doors. When no one’s looking.” And bodies are important, otherwise we wouldn’t have them. Though we all seem to be “mismade” in a sense, Manichaeism isn’t the way to go, nor is ecstasy-nullifying asceticism. But I must admit that I think too much trust in our own power and from-within salvation falls short, and perhaps the orgiastic might cloud our metaphysical vision. I wonder: Are we just bodies? What remains in the comedown of post-sex detumescence, after the mucus membranes cool off, when we catch our breaths and more than bodily matters matter? What lies in the wake of impotence, old age, infirmity? I’m not sure if Catherine has thought that far yet, and I wonder if Sasha Grey has. I’d love to hear more from her.

Mastering one’s craft, vanquishing adversaries, demanding and receiving sexual satiety, and striding confidently into the future are good and reassuring – but you know what they say about the best-laid plans of mice and women.

– David Herrle