with John Bew, Martyn Frampton, Dan Jones and Claudia Renton

with John Bew, Martyn Frampton, Dan Jones and Claudia Renton

Rating: ❤❤❤❤

Shakespeare’s Polonius said that brevity is wit’s soul, so he’d certainly bash the “limbs and outward flourishes” of my usual long-winded tedium, but I must say that, more often than not, the longest and heaviest biographies seem to be the best ones. This may be due to the fundamental evasiveness of truly holistic written portraiture of any human, let alone historic and well-accomplished ones. While there’s a powerful and popular desire to portray a person with poetic pith, whittle her or him down to a convenient little “Rosebud,” the challenge of composing a tortuous, kaleidoscopic study of a worthy individual also compels. Sometimes quick, direct roads are needed; other times we delight in scenic routes. Of course, there’s a vast difference between, say, Penguin Random House’s snack-size Who Was? series and epic tomes by Harold Bloom, between CliffsNotes and Simon Callow.

I think the attractiveness of more involved biographies is the tendency for them to be works of art in themselves, transcending their subjects and intensifying the biographers’ glow, forever associating them with the figures of whom they wrote. James Atlas writes in The Shadow in the Garden: A Biographer’s Tale: “[Richard] Ellmann’s Joyce didn’t read like a biography: it read like a work of art…and behind its façade of objectivity you could detect, if you listened closely enough, the biographer’s own voice.” (Some personal favorites of mine are Boswell’s The Life of Samuel Johnson, Peter Gay’s Freud: A Life For Our Time, Harold Bloom’s Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human, Marie Antoinette by Antonia Fraser, Adolf Hitler by John Toland, The Brontes by Juliet Barker, Oscar Wilde by Richard Ellmann, Greta Garbo: A Life Apart by Karen Swenson and, fairly recently, Eric Metaxas’ splendid book on Martin Luther and Diarmaid MacCallum’s Thomas Cromwell study.) Nevertheless, less is never unacceptable if it’s done in such a way that leaves a reader leaving satisfied, having consumed a substantial morsel rather than a teasing crumb.

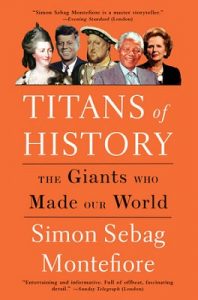

What historian Simon Sebag Montefiore has done with Titans of History: The Giants Who Made Our World is remarkable, to say the least. He has managed to provide what seems to be a trove of biographical information in vignette-ish form, compiling about 200 biographical profiles of famous royals, heroes, politicians, artists, cretins, jerks and geniuses in a compact, encyclopedic volume. “My aim is that these short accessible and vivid biographies will encourage and inspire readers to find out more about these extraordinary individuals,” Montefiore says in the book’s introduction. And this is precisely what he achieves. Only the incorrigibly incurious could resist thirst for further learning about most, if not all, of the selected persons.

The titans before and after Christ aren’t presented in alphabetical order, nor in any consistent chronological order. At the beginning is iconic Egyptian pharaoh Rameses the Great, and greats such as Anne Frank and Elvis are located near the very end. (I find such quiltwork comfortable, since this is how I arrange my bookshelves at home.) Book are finite while history is vast and dense, so there are many more omissions than inclusions. China’s Empress Zhao Wu is spotlighted while Ronald Reagan is relegated to mentions in Margaret Thatcher’s and Gorbachev’s sections, for instance. Also, some titans have longer sections than others. For whatever reason, Bolivar gets about 10 pages (maybe the most in the book) while Lord Byron gets hardly three pages! (My Lord!)

Montefiore’s picks would be difficult to dispute: there’s a good mix of household names and less sung individuals, and his cool style and knack for encapsulating relevant knowledge make every one of them quite interesting. Expected top-tier names such as Alexander the Great, Caesar, Jesus, Saladin, Marcus Aurelius, Elizabeth I and Catherine the Great mingle with the lesser taught likes of, say, Ben-Gurion and Tokugawa Ieyasu. And international/sociopolitical titans don’t steal all of Montefiore’s stage. The book also features Oscar Wilde, Maupassant, Sappho, Jane Austen, Beethoven, Casanova, Sarah Bernhardt, Picasso, Toulouse-Lautrec, Al Capone – even Jack the Ripper.

Montefiore provides handy background information on each person, highlights their important qualities and actions, and makes sure that at least one key anecdote or tidbit is slipped into the reader’s future-conversation wallet or purse before moving on to the next subject. Some examples: “The philosopher Plato is said to have considered Sappho the tenth muse.” Oskar Schindler’s ex-wife Emilie complained that “he gave his Jews everything. And me nothing.” “Julius Caesar, a superb general in his own right, was plunged into deep despair whenever he pondered Alexander’s achievements.” “[Cleopatra] was probably not beautiful….but she possessed a ruthless aura like Caesar himself and shared a taste for sexual theatre and adventurous politics.” “In total [Richard III] had ten wounds, suggesting a brave death in the fray.” And for whoever has wondered about the great Chinese philosopher Confucius, his name derives from “Kongzi” or “Kongfuzi,” meaning “Master Kong.”

Throughout Titans of History Montefiore exhibits disciplined factuality, the afore-quoted “façade of objectivity” is certainly not his style. He tends to opine and make judgments, but none of them are extreme or spoil biographical soundness and credibility. Perhaps one statement might cause some folks’ eyebrows to raise, I guess: “There is no reason to doubt that Moses, the first charismatic leader of the monotheistic religions, did receive a divine revelation after such an escape from slavery.” Regardless, the more typical Montefiorean assertions are exemplified in the following lines. Oliver Cromwell’s “burning commitment to God and the English people, rather than personal ambition, marks him as the greatest king that England ever had.” For Montefiore the written correspondence between Catherine the Great and her lover Potemkin amounted to “the most outrageous and romantic letters ever written by a monarch,” and Jane Austen “transformed the art of writing fiction.” “There was no one else like her,” he says of Margaret Thatcher, whom he considers “the greatest British leader since Churchill.” (I agree with him, but oh, how this surely rankles many readers out there!)

Besides the lack of alphabetical and strict chronological order, grouping by beneficence or lack of it also is absent. “When I started this project, I tried to divide these characters into good and bad,” Montefiore explains, “but I realized that this was futile because many of the greatest…combined the heroic with the monstrous.” Really, it’s both unsurprising and amazing how so many historically famous figures also deserve infamy. Truly, humanity is commonly inhumane; individuals are so much more complex and even paradoxical than the children’s game of cops and robbers. I think astute appreciation of people, particularly prominent world-movers, artists, celebrities and such, requires intellectual maturity, wisdom – and a sort of forgiving spirit, an ability for disgust with wrongdoing while simultaneously giving due credit for praiseworthy feats and other positive aspects. For instance, in the section about Israel’s King David Montefiore writes:

David was portrayed in the Bible as first a holy, ideal king but also a superb warrior, a poet and harpist, a flawed warlord and adventurer, a collaborator with the Philistines, an adulterer, even a murder…The portrait of David is thus a surprisingly rounded and human one.

It’s no wonder that David is thought to have written most of the biblical Psalms, those moody lyrics of pendulous emotions, desires and gripes. Only folks who appreciate the Psalms and stuff like them can really tolerate the non-math of the human heart, the prickles and the goo (to steal from Alan Watts). For this very reason Montefiore was able to say that Alexander the Great “could be merciless” but had a “nobility of spirit.”

When history is surveyed from a nerd’s-eye view, an exhausting, sobering, depressing familiar pattern, besides the manic/meteoric/parabolic/entropic rise-and-fall rule of human existence, is noticed: idealism, even utopianism (especially utopianism, really) quite often degenerates into purgation, bloodbath and despotism. As Montefiore points out, even lauded Constantine the Great “was no saint but a brutal, bull-necked, flamboyant soldier who murdered his friends and allies and even his closest family.” Persecution, mass murder and oppression are history’s norms, not its exceptions. (I always point to Reign of Terror France and practically yawn with Gore Vidal haughtiness: “This is what democracy looks like.”) The grisly tantrums of rulers before the twentieth century obviously were preparation for an entirely new kind of magnificent slaughter that wasn’t entirely new.

Titans of History covers the violent, autocratic likes of Sulla “the general and dictator whose murderous rule sounded the death knell of the Roman Republic,” ultra-narcissistic Caligula, “depraved megalomaniac” and “intelligent puppeteer” Empress Zhao Wu and murderous Empress Cixi, the Byzantine Empire’s Basil the Bulgar Slayer, fanatical persecutor Torquemada, and the atrocious Conquistadors Cortes and Pizarro. Of course, the book focuses on the trademark dastardy of Adolf Hitler, whom Montefiore calls “the embodiment of the historical monster, the personification of evil,” but it must be admitted that the Bolsheviks innovated terror and organized execution long before the Nazis took power in Germany. And then there’s Josef Stalin, who seems to be the apt pupil of many of history’s brutal precursors. He either consciously emulated or naturally echoed the sanguinary titans of atrocity. Montefiore sums it up perfectly: “Stalin and the Bolsheviks, along with his great foes Hitler and the Nazis, brought more misery and tragedy to more people than anyone else in history.”

Iran’s infamous Nader Shah, who Montefiore says “sank into paranoid brutality, frenzied killing and finally the insanity that led to his murder,” was one of the many cataclysmic figures who prefigured Stalin. “Thousands died at his hands; his taxes and wars ruined his own people, and at his death, his empire fell to pieces,” writes Montefiore, also adding that “centuries later, Stalin studied Nader Shah as a man to admire for his flawed but pitiless grandeur.” One who must never be omitted from this long disaster recipe is Robespierre, “the prototype of the modern European dictator” who “helped inspire the totalitarian mass killings of the twentieth century.” 100,000+ people were killed under his watch before the Terror also gulped down him. Montefiore could be describing Stalin as well as Robespierre when he writes that the latter believed that “revolutionary virtue and the Terror went hand in hand.”

Russia itself had a long history of evil that inevitably spawned Stalin’s hell on Earth. “Tragic but degenerate monster” and “shrewd tyrant” Ivan the Terrible was basically “a demented, homicidal sadist” whose death squads (oprichniki) specialized in torture, brutal murders, massacres and executions. He even killed his own son. Unsurprisingly, Stalin was inspired by the oprichniki and considered Ivan a “teacher.” Peter the Great is another huge stage-setter for the Great Terror. Despite his reformism, “at heart he was a brutal autocrat” and “the prototype of the ruthless yet revolutionary Russian ruler.”

As is usual, the goons were worse than their boss. Soviet secret-police head Nikolai Yezhov, the diminutive “Bloody Dwarf,” lead a “murderous witch-hunt [that] was known as the Meatgrinder,” approaching random mass murder as a quota strategy, infamously killing a thousand people within a five-day period. Yezhov feel from gross and was replaced by Lavrenti Beria, a “psychopathic rapist and enthusiastic sadist” who was particularly creative in the art of torture.

Some of Stalin’s foes were hardly different. Spain’s wannabe-Hitler, Francisco Franco, who Montefiore rightly says was “in some ways the forgotten tyrant” and “truly one of history’s monsters,” reveled in terrorism and mass murder, such as the Picasso-incensing Guernica bombing in 1937. During the Spanish Civil War the USSR-backed Red Terror supported the anti-Franco republicans, and it slaughtered tens to hundreds of thousands of people, including many Christian religious figures.

Refreshingly, not every ruler was a sadistic thug. Though he had absolute power, Julius Caesar “did not rule by terror and was forgiving and clement, using his power for the greater good.” Another relatively amiable Roman was Stoic Marcus Aurelius, who had “an unselfish and pragmatic approach to governing his empire.” Much, much later Aurelius (and his inspirer Epictetus) interested American founders such as Thomas Jefferson, whose “power was in his pen” rather than in an executioner’s axe. He was part of a truly unique revolution that still stands out in history for its lack of deliberate atrocious reprisals and subsequent tyrannical terror. Yes, Jefferson machinated against Alexander Hamilton and contradicted his former caution with executive-power moves as president, but in general he is a prime example of an enlightened, conscientious leader. Montefiore points out that Jefferson avoided public speech, which is ironic in comparison to another basic inspiration for the American Forefathers, the genius Roman Cicero, who was “a supreme master of the spoken word” and “introduced to Rome the Greek ideas that formed the basis of Western thought for the next 2000 years.”

Obnoxiously enough, I’ll list other titans who appear in the book: Nebuchadnezzar II, Cyrus the Great, The Buddha, Sun Tzu, Leonidas of Sparta, Herodotus, Alcibiades, Plato, Aristotle, Qin Shi Huangdi, Hannibal, the Maccabees, Herod the Great, Nero, Attila the Hun, Muahammad, Einstein, The Three Pashas, Ataturk, Picasso, FDR, Mussolini, Tojo, Gandhi, Lenin, Proust, Shackleton and Roald Amundsen, Churchill, Ibn Saud, Bede, Charlemagne, Genghis Khan, Frederick the Great, Tamerlane, Henry V, Joan of Arc, Vlad the Impaler, Mehmet II, Savonarola, Isabella and Ferdinand, Columbus, Selim the Grim, Michelangelo, Barbarossa, Babur, the Borgias, Magellan, Henry VIII, Suleiman the Magnificent, Elizabeth I, Akbar the Great, Walter Raleigh, Galileo, Shakespeare, Abbas the Great, Wallenstein, India’s Aurangzeb (Alamgir) Samuel Pepys, Louis XIV, Isaac Newton, Marlborough (John Churchill), Captain Cook, George Washington, Touissant Louverture, John Paul Jones, Talleyrand, Mozart, Horatio Nelson, Duke of Wellington, Napoleon I, the Zulu Shaka, Balzac, Pushkin, Alexandre Dumas, Disraeli, Garibaldi, Napoleon III, Abe Lincoln, Darwin, Dickens, Bismarck, Florence Nightingale, Louis Pasteur, Leo Tolstoy, Leopold II, Tchaikovsky, Clemenceau, Kaiser Wilhelm II, David Lloyd George, Nehru (and Indira Gandhi), Mao Zedong, writer Isaac Babel, Marshal Zhukov, Ernest Hemingway, Heinrich Himmler and Reinhard Heydrich, Ayatollah Khomeini, George Orwell, Deng Xiaoping, Kim Il Sung, Kim Jong Il and Kim Jong Un, JFK, Gamal Nasser, Nelson Mandela, The Shah, Pol Pot, Boris Yeltsin, Saddam Hussein, Muhammad Ali, Pablo Escobar and Osama bin Laden.

After all of those textbook-worthy names (and the implied missing names), Titans of History concludes with a nameless titan. Montefiore writes that Oskar Schindler, the renowned rescuer of over 1,000 Jews in Nazi Poland, “demonstrates that real heroes are often not pious and conventional but worldly rogues, eccentrics and outsiders.” And anonymities, apparently. I refer to who Montefiore calls The Unknown Titan and is commonly referred to as “Tank Man”: the guy holding the briefcase who stood in front of a tank in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square in 1989. Martial law declared, thousands of protestors killed and tens of thousands injured, the Communist Chinese state challenged – and an obscure individual played chicken with a tens-of-tons tank, becoming both an iconic twentieth-century photojournalism image and everlasting spiritual symbol. After the incident, Tank Man, whose identity is still a mystery, was never seen or heard from again. Poetically ironically, Montefiore caps his book with an anonymous hero, clarifying that every person needn’t make a name for her-/himself, and that the name doesn’t necessarily make the person – or titan. The book’s closing sentence reverberates with due reverence: “Tank Man remains an inspiration: the unknown hero who represents all the other unknown heroes.”

David Herrle