Rating: ❤❤❤❤

Swindon Wasn’t Peyton Place

I discovered INXS before discovering XTC. I delighted in the coolness of the former’s name sounding out “in excess” even more than the derivation of, say, U2, thanks to the sensual, epicurean current in the acronymed phrase. Likewise with the “ecstasy” in XTC, which half-inspired INXS’ name. But, if one really thinks about it, there’s not much – if any – ecstasy in XTC’s work, at least not in the commonly associated sense of the term. Unlike horndog-Michael Hutchence-headed INXS, Andy Partridge-/Colin Moulding-led XTC seems relatively corseted and erotically mum (except for in rarities such as “Pink Thing”), and their catalog is actually almost as asexual as that of the band Rush. Andy Partridge summed up this apparent libidinal neglect over 30 years ago. “I can’t talk about my hot babe with her leather and whip, or meeting my cocaine dealer,” he said. “I like to write about what’s going on around the town.” (Obviously, his hometown Swindon wasn’t Peyton Place.)

Despite my preference for carnality in rock/pop music (and my fundamental dislike of the Beatles and most emulators of them), I appreciate XTC’s uniqueness, oddness and musical virtuosity, and their preponderant lovely, extremely touching moments. The band abounds with lyrical and musical sensuality, and their songs often reach ecstatic poetic heights – such as in the rapturous gales of strings in the chorus of “Sacrificial Bonfire,” the starry blast accompanying “I have watched the manimals go by” in “Jason and the Argonauts,” and in the affecting keyboards after the choruses in “Ball and Chain,” whose melancholic majesty and sublimity figuratively and literally lift, hurt and heal my heart every time I listen (regardless of my dislike for its silly Luddite/Year Zero-like ethic). I’ll forever associate the song with the early bloom of a brief but deep romance between me and a girl-friend-turned-girlfriend back in high school, since I shared the song with her right before our first long-pent kiss. And the last two minutes of “Wake Up” on The Big Express? Great, glowing, glorious!

Then, still speaking of aural loveliness, there are “All of a Sudden (It’s Too Late),” “Season Cycle,” “Mermaid Smiled,” “Summer’s Cauldron” and, of course, “The Loving”: the warm, cuddly, tolerably utopian anthemic parallel to The O’Jays’ “Love Train,” INXS’ “Baby, Don’t Cry,” USA for Africa’s “We Are the World” and R.E.M.’s “Shiny Happy People.” XTC’s injections of transcendence, tenderness and relatable subjectivity prevent them from being exhausting, overly tedious or offensive. For every ten Dadaist/collagist/stream of pretentiousness R.E.M. song, a “You Are the Everything” or “Nightswimming” is needed as cohering antidote. Likewise with XTC. In reply to interviewer Bill DeMain’s question about tricks to unfreeze writer’s block back in 1999, Andy Partridge said: “One of them is to turn my brain to like an insanity or nonsense switch and just unite any words that come into my head, whatever they are.” “If you can spew out this gibberish,” he explained further, “what you’re doing is getting in touch with your subconscious store cupboard.” Thank goodness for the coherent-metaphorical tenderness of “Another Satellite” and “Mayor of Simpleton!”

I have a love/eye roll relationship with any band that tends toward semi-goofiness, off-kilter topics, dark humor and obvious satire: such as, say, the absurd/savant Talking Heads or often obnoxiously over-jokey Primus (whom I love nonetheless). Curiously, these two bands, as well as XTC, are prone to an off-putting mathematical tightness, discordance and puckered monotony, and much of their musical qualities disallow chill ambience or distraction, similar to much Eastern stuff. For example, “Seagulls Screaming Kiss Her, Kiss Her” could have been a lipstick-spit-sticky, compulsive song of urgent Eros, but its lyrics are alienated and roboticized by alienating and robotic music.

So, for me, XTC is a band of songs rather than albums, their particulars surpassing their wholes, and they could begin and end with English Settlement if it came down to it. The runner-up is certainly Skylarking, which is the band’s most cohesive work and classifiable as a concept album. Regardless of vicissitudes, stinkers and a good number of so-so songs, XTC has maintained originality and worthy instrumentation over their entire career. Before moving on I’ll toss out several other songs that I find brilliant:

English Settlement’s punch-drunk “Leisure” and “Melt the Guns” (verrrry in spite of its too-simple/anti-self-defense utopian sermonizing and verrrry much for its epic two-minute-plus Talking Heads-like interlude) Mummer’s “Wonderland,” Nonsuch’s “My Bird Performs” and Beach Boy-delightful “Then She Appeared” (containing the later-title-seeding lyric “apple Venus”), Apple Venus’ “Knights in Shining Karma” (with its Joni Mitchell-and-Jaco Pastorius-in-Hejira-like guitar sound), Wasp Star’s “Playground” (whose glorious opening riff sounds similar to the intro to “Respectable Street”) and riffy “Stupidly Happy,” Black Sea’s “Love at First Sight” (whose guitar “solo” reminds me of Minutemen’s D. Boon), Apple Bite’s “Spiral,” Oranges and Lemons’ “King for a Day” (which is cousin to Tears For Fears’ “Everybody Wants to Rule the World”) and gives-me-good-shivers-and-lumps-in-my-throat “Chalkhills and Children.”

Here’s where I lose favor with what may be the majority of XTC fans: “Dear God” is not included in my pro list. There. I said it.

(If you want to skip the following section, due to its long-windedness and pedandtry, please click here.)

“Dear God?” Dear God!

Almost invariably “Dear God” is the first song title out of folks’ mouths when I mention the hype-deserving masterpiece Skylarking, and I wonder from where the mass enthusiasm comes. On the rare occasion that I do let it play, it’s an uncomfortable experience – yet not wholly, thanks to the beguiling music. The song isn’t a clever commentary, nor an enlightening corrective against so-called superstition and retrograde delusion. Not quite as sophomoric and lame as John Lennon’s creepy “Imagine” or as toxic and sneering as Nine Inch Nails’ “Terrible Lie,” this overly popular (and overrated) atheist diatribe is presented in petition or letter form, and the lyrics inventory some typical main failures and neglects of the non-existent (notably Christian) God whose unreality is supposedly evinced by atrocity’s and tragedy’s earthly flourishment: wars, drowned babies, starvation and so on.

The vocals by an eight-year-old girl at the beginning and end are disturbing (more so these days because my dear daughter is now eight), especially the way she enunciates the final “dear God” in a faltering, despairing half-whisper. Overall, the tone (even the tune) of the song seems to borderline on eerie, devoid of the counterbalancing invigoration of, say, Metallica’s hopeless ballad “Fade to Black” or The Smiths’ “Asleep.” (Even The Godfathers’ grim-but-catchy “Birth, School Work, Death” wishes for afterlife paradise.) Maybe more obnoxious is the fact that the sentiments range from banal to cliché to banal again throughout the song. For example, how can anyone take these lines seriously? “I pray you can make it better down here./I don’t mean a big reduction in the price of beer.” Really? Nothing better rhymed with “here?”

I have a Christopher Hitchens and a C.S. Lewis perched on my shoulders at all times, and, as a Psalmic Eeyore, I’m pendulous between a sense of Presence in the Absence and dreadful despair before the vast expanse of apparent absurdity before which Pascal trembled – but whenever there’s indelicate handling of doubt, denial, disgust and derision about certain details entailed in the fundamentally endearing drama of the God-Man (as opposed to Man-God), I become oddly defensive. “When a cause trumpets, I long for silence,” I always say, “But when the frivolous reigns, I want manifestos.” Likewise with metaphysics. On one hand the capriciousness, precariousness, natural and common atrocity and basic absurdity of existence preclude firm belief in ultimate purpose, let alone divine design and direction. While I dread future nothingness after checking out of a chance-determined infinity, I’m somewhat creeped out by a continuance in a God-chosen eternity. Sometimes I desire a reliable Heaven, other times I think it’d be less stressful if “Zap, you’re gone completely” were guaranteed. Mind you, I’m not a denier of deniers, nor a resenter of the resentful or a disser of disbelievers. And I do my share of eyebrow-raising, doubt broadcasting and flirtation with existentialism and even nihilism. But during my fluctuations there’s Something/Someone I can’t let go of, and the idea of the loss of such transcendent stuff irks me.

At the very least, the inescapability of my belief, however tattered and threadbare it becomes, might be comparable to what seems to flicker in an uncharacteristically agnostic/slightly-askew-with-his-staunch-antitheism statement by Christopher Hitchens at the end of the documentary Collision: Christopher Hitchens vs. Douglas Wilson, in which he recounts a conversation he had with Richard Dawkins:

I said if I could convert everyone in the world…not convert, if I could convince to be a non-believer and I’d really done brilliantly, and there’s only one left. One more, and then it’d be done. There’d be no more religion in the world. No more deism, theism. I wouldn’t do it. And Dawkins said, “What do you mean you wouldn’t do it?” I said, “I don’t quite know why I wouldn’t do it.” And it’s not just because there’d be nothing left to argue and no one left to argue with. It’s not just that – though it would be that. Somehow if I could drive it out of the world, I wouldn’t. And the incredulity with which he looked at me stays with me still, I’ve got to say.

Whenever stuff like “Dear God” intersects, my mind invariably goes to how Dostoyevsky was troubled deeply by Holbein the Younger’s Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb back in 1867. The painting depicts a stone-dead corpse in obvious decay: wretched, disturbing, the metaphysical opposite of religious icons. “And if Christ has not been raised,” goes the Bible’s I Corinthians 15:17, “your faith is futile.” So, we can see how crucial (in the etymological pureness of the term) this is. So affected, Dostoyevsky made the painting a central concern in his novel The Idiot, in which a main character, Ippolit, says that the image evinced that “the body on the cross was therefore fully and entirely subject to the laws of nature.” Later Ippolit goes on to speculate about how the corpse would have struck onlookers:

The people surrounding the dead man, none of whom is shown in the picture, must have been overwhelmed by a feeling of terrible anguish and dismay on that evening which had shattered all their hopes and almost all their beliefs at one fell blow. They must have parted in a state of the most dreadful terror, though each of them carried away within him a mighty thought which could never be wrested from him.

Which brings me to the almost literal association of XTC’s “Merely a Man,” which is, in contrast to “Dear God,” buoyant and frivolous. Satirizing the Christ motif, the main thrust of the lyrics offer humanistic salvation: “I’m merely a man,/And I bring nothing but love for you.” Instead of promising “rainbows with some golden pot” (what religion does that?), this mere man assures us “that with logic and love we’ll have power enough,/to raise consciousness up and for lifting humanity higher.” Logic and love, huh? Oh, they have their important places, for sure, but if I’ve learned anything in my life so far it’s that logic is overrated and love is not enough.

Logic first. In the interest of saving time, I usually let G.K. Chesterton cut logic down to size. In a Daily News article back in 1905 he pointed out that “logic and truth, as a matter of fact, have very little to do with each other…You can be as logical about griffins and basilisks as about sheep and pigs.” Somewhat similar to Ayn Rand’s later views on premises and axiomatic thinking, he saw truth itself as an indispensable prerequisite for obtainment of truth rather than the reverse: “Briefly, you can only find truth with logic if you have already found truth without it.” Then there’s Dr. Francis A. Schaeffer, who noted that “logical positivism claims to lay the foundation for each step as it goes along, in a rational way. Yet in reality it puts forth no theoretical universal to validate its very first step.”

Love next. Again Dr. Schaeffer emphasizes what he sees as a problematic lack of an actual person behind Oz’s curtain, so to speak:

Modern man quite properly considers the conception of love to be overwhelmingly important as he looks at personality. Nevertheless, he faces a very real problem as to the meaning of love. Though modern man tries to hang everything on the word love, it can easily degenerate into something very much less because he really does not understand it. He has no adequate universal for love.

Of course, just as when Huey Lewis and the News tout “the power of love,” XTC does touch on an indispensable thirst and need for love in humanity. Indeed: “All around the world every boy and every girl needs the loving.” My nausea for utopia doesn’t necessarily scoff at our innate thirst and need for Valentines and affection.

In Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov skeptical, depressed Ivan, who renounces faith in God because of the apparent lack of intervention in children’s suffering (a primary gripe in “Dear God”), blasts his faithful, semi-naïve brother Alyosha with undeniable examples of fundamental human horror, such as a child abused by parents and a child ripped apart by dogs at a sadist’s command, summing up the impediment against his faith with a powerful question: “But then there are the children, and what am I to do about them? That’s a question I can’t answer.”

When Alyosha insists that “a great deal of love in mankind, and almost Christ-like love” persists in the midst of misery, Ivan rebuts that “Christ-like love for men is a miracle impossible on earth. He was God. But we are not gods.” Even Myshkin, the “truly good man” in Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot, can’t provide redemption to whom he ministers. Why? Because he’s a man, merely. “Nothing but love,” at least on a human level, seems to fail us, and total belief in it makes one vulnerable to utopian amazement and shock at sudden eruptions of atrocity even in the loveliest and lovingest of havens.

On Martin Luther King, Jr. Day everyone and their cousins like to quote (and misquote) what MLK said about hate’s incapacity to extinguish hate in The Strength to Love, a book which, I think, isn’t appreciated for its radical prescription of forgiveness and loving the (real or perceived) unlovable. It’s easy to love the lovable. MLK’s standard was so high, Christ-high, higher than most of us would even imagine trying, let alone achieving. Even MLK, a mere man, not a God, didn’t – couldn’t – achieve it.

As Dostoyevsky apologist/expounder Nikolai Berdyaev says, “the sin and powerlessness of man in his pretention to almightiness are revealed in sorrow and anguish,” which is applicable to something Andy Partridge said to Bill DeMain: “People say that the best material, the best art, is made from either extreme joy or extreme misery…I’ve been through incredible lows and incredible highs, so I’d say that whoever said that was probably right. Extreme misery or extreme joy are great energies.” I think The Savage in Aldous Huxley’s (vastly misunderstood) Brave New World puts this best when he rebuts The Controller’s endorsement of mass comfort over freedom, happiness over suffering: “But I don’t want comfort. I want God, I want poetry, I want real danger, I want freedom, I want goodness. I want sin.”

Lucky for us, genius Andy Partridge seems to have figured out how to balance heaviness and effervescence, thus XTC offers us “stupidly happy” songs as well as songs of melancholy. However, though I admit overreaction about it, stuff like “Dear God” bugs me, and much of that annoyance comes not only from its contradiction of the true nucleus of art-making but also its utopian implications, for far from achieving redemption and durable concord via “a big reduction in the amount of tears,” as the “Dear God” lyrics call for, there’s much to be learned and born in highs and lows, in misery and joy, in sickness and in health, from the foam to the gravel.

“Not Being Quite Right”

Whatever they disbelieve or believe, however pedestrian their atheism, whether they are or aren’t too Beatlesy or Beach Boysy, I think it’s safe to say that XTC has branded the music world with a peerless three-letter stamp. Still, it’s pretty difficult to sum up the band in a category and to try to explain them and their sound to neophytes. No single genre contains them; no simple comparison puts them in perspective. Trying to get to the bottom of XTC is best done with other fans, because the band is like an abstract-expressionist gallery whose art speaks to, changes and aligns with different people in countless peculiar combinations – and the uninitiated haven’t been warped enough to even begin to get them. In Britpop! (a book that is inexplicably and woefully low on XTC information) critic John Harris’ insight semi-redeems him when he writes that “XTC’s music often came with a jarring sense of something not being quite right.” Post-punk, new wave, progressive, dork rock – whatever. Really, they’re…nonsuch.

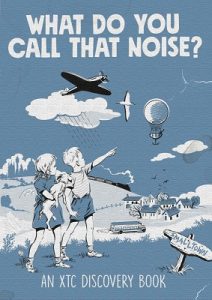

“There was nothing that was sufficiently massive enough to define what the XTC sound was,” says XTC guitarist Dave Gregory, a person who should know. “We were free to be as imaginative as he could be.” Know from where I got that quotable tidbit mined from a Hugh Mankivell interview? Mark Fisher’s What Do You Call That Noise? An XTC Discovery Book, a compendium recently released by Limelight, publisher of the long-lived XTC’s Limelight fanzine and The XTC Bumper Book of Fun for Boys and Girls: A Limelight Anthology. Terrifically prolific, knowledgeable, sincere and conscientious, editor Mark Fisher “wanted to know what the music sounded like on the receiving end,” so he turned to the ears and hearts of 40 musicians who delivered more than enough worthy feedback on the band to which he’s dedicated so much of his time for decades. I must say, as I read on and on, taking notes along the way as I always do, I paused and marveled at the density and scope of this most recent Limelight enterprise. At first, I was disappointed at the realization that most of the musicians, besides actual XTC members, were not what the world would call “A-list” and widely recognized, but I warmed to and appreciated the unconventional and very worthy focus not too long afterward.

My acclimation and approval occurred early in book, thanks to a piece by keyboardist Imogen Bebb called “Things We Did in Class,” in which she described “Mayor of Simpleton” as “a wall of sound that never once falters in pace or effortlessness.” This is followed by “Chalkhills’ Children,” a shared correspondence between Bebb and two other XTC fans, Mia Rankin and Krysten Leland. Inspired by Skylarking’s “Summer’s Cauldron” Leland says that “the look on my face as the chirps began” escapes description, to which I can wholeheartedly relate. And Rankin knocks poignancy out of the park when she says that “there’s an XTC album for every mood.” Absolutely. They’re wide-gamuted and eclectic, and they’re not easily shaken from one’s musical repertoire. “And that’s the ‘downside’ to XTC’s music,” says author/illustrator/editor David Yurkovich. “It’s addictive. It’s like brainwashing.” None other than New York Dolls’ Steve Conte provides a perfectly relatable assessment, in regard to the “Take This Town” song: “Once again XTC surprised me that when I first hear it I think ‘Nah, this is too weird I’m not into it,’ and then after a few listens I’m a true believer, amazed by its creative genius.”

As far as I’m concerned, the finest feature in What Do You Call That Noise? is Mark Fisher’s “A Chain to Hold All Battleships in Check,” an epic collection of musicians’ XTC spiels, revolving around Inherited Tracks and Bequeathed Tracks. Like passers-on of a chain letter or tagged participants in Top Ten Lists on Facebook, individuals are given XTC tracks on which to comment and then give other tracks to the next individuals. This snowballs into an almost overwhelming exploration of XTC’s effect on people, and the spiels yield a ton of splendid observations and shiny lines. The Liquid Scene’s bassist Becki diGregorio says that the music of “Poor Skeleton Steps Out” “offers us an aural image of what dancing skeletons might sound like,” something that’s obvious once it’s articulated, but mostly subliminal otherwise. Barenaked Ladies’ Steven Page calls “Earn Enough for Us” “very McCartney-like;” David McGuiness of Concerto Caledonia says of “All of a Sudden” that “there is so much space in it;” Gregory Spawton of Big Bad Train calls “Chalkhills and Children” “five minutes of extraordinary beauty” and “magic that seems to float above the ground;” for Fassine’s Laurie Langan, “Another Satellite” “lyrically bruising” “achingly beautiful;” and for musician/singer Anton Barbeau “Senses Working Overtime” is “a life-changing song” and “a perfect piece of music.” (Has he peeked at my teenage diary?)

Needless to say, much is made of the actual construction of XTC’s music. As Erich Sellheim, whose YouTube-aired, German-language XTC cover songs were painstakingly rendered by adjusting the syllabic count and rhyme in translation, puts it, “so many of us aren’t content merely consuming XTC’s music; we need to talk, write, sing, even dance about it.” It’s fascinating to learn what actual music composers think of the band’s compositions. “I love the juxtaposition of what appear to be straightforward, well-crafted songs,” says Jellyfish’s Jason Falkner, “with this element of atonal, discordant playing over it, mainly in the guitar department.” This peculiar style is owed to the entire band, of course, but frontman Andy Partridge deserves special attention, which is certainly given many times throughout What Do You Call That Noise?, particularly in the “And All the World is Keyboard Shaped” section, in which musicologist Robert G. Rawson makes the excellent point that “unusually in pop music, Partridge’s songs for XTC are highly linear in concept – they depend more heavily on independent melodic lines than on vertical, chord-centered approaches.” Rawson also observes that such an approach “permits any sound to follow any other sound,” which enables Partridge to focus on “where the music and images/narrative are going and less, if at all, about vertical considerations and conventions of form.”

False Lights’ Jim Moray points out that “Andy understands harmonies by stacking notes…Instead of thinking holistically, he’s constructing out of fragments stacked on top of each other,” and Tin Spirits’ Daniel Steinhardt boils down both the man and the band when he says that Partridge’s “songwriting very rarely goes to the place you think it’s going to go, therefore listening to XTC is never going to be a passive experience.” Steinhardt elaborates:

…I find it amazing to hear someone who can effortlessly break the rules, not for the sake of breaking the rules, but because that’s where he’s artistically led. He creates these beautiful melodies that become so much part of the song that you can no longer think of any other possible melody over those changes.

In another Mark Fisher section, “A Chord in My Hand,” Partridge himself provides a more detailed (albeit somewhat esoteric) glimpse of his musicianship, with a focus on his recording preferences. Some examples follow. “Bass – always leave till last…Find your space better and don’t over-play like many people who track bass and drums first can be prone to do.” “Best Bass – Split/copy bass to two tracks. Have nothing above, look for deep bass track…Compress and limit hard. High bass track = nothing below look, sculpt with, EQ and compress to fill in detail in track.” “Acoustic Guitars – mic away from hole, at neck join or bridge.” “Live Drums – kits mix themselves, so one mic usually does the trick. Try to get separate bass drum and overhead if you have limited space…” “Number One – don’t record/master too loud, allow for some dynamic range and let the music breathe.”

Andy Partridge is absolutely indispensable, as far as I’m concerned, so the book’s end piece, “Life Begins at the Hop,” which is about six reunion concerts starring Terry Chambers and Colin Moulding – and no Partridge – couldn’t possibly attract my interest. The best effort I could ever muster in such a situation is post-Roger Waters Pink Floyd, thanks to the authority of David Gilmour, but I can’t accept, say, a Morrisonless Doors, a Hutchenceless INXS, a Rothless – or Hagarless – Van Halen. Sorry.

Speaking of band subtractions and additions, in “Me and My Mate Can Sing” Mark Fisher converses with keyboardist Barry Andrews, who was a two-year member of early XTC (“a historical blip,” in Fisher’s words) and better known for his career in the band Shriekback for four decades. Though this section doesn’t feature much about XTC at all, Andrews, who is also a sculptor and furniture maker, turns out to be quite an interesting person – and he even references psychologist Jordan Peterson’s five-criteria personality test.

I delight in bass more than guitar, and there’s not much more for me to say about Colin Moulding’s lovely compositional contributions, but I do delight in percussion more than guitar and bass, so the book’s focus on drummer Terry Chambers, who Marco Rossi says has “a mathematically precise deployment of unusual, cyclical patterns and carefully considered recurrent fills that somehow combined a rod-straight chronometry with a subtly weighted sense of swing,” is much appreciated. Beyond Rossi’s section there is “Do You Know What Noise Awakes You?,” featuring drummers’ spiels on Chambers’ drumming. My favorite is the buzz about English Settlement’s best track, “Ball and Chain,” of course. For instance, Sebastian Ruger: “In English Settlement Terry discovered his Rototom that he puts everywhere…Terry knows where to put things when, to carry the song and at the same time not to interfere with the vocals. He really has a great ear.” And Todd Bernhardt: “’Ball and Chain’ is very unusual…It’s athletic, musical and melodic because he’s using the tuned toms with the rest of the instruments.”

My second favorite section in What Do You Call That Noise? is the testimonial “Emotion at the Drop of a Hat.” A selection of folks share how and why XTC served as lifelines for them during their lives’ tribulations. One of a few “Anonymouses,” who was “lonely, sad and depressed,” Asperger’s-diagnosed, floundering in school and bullied, found refuge in White Music and its “weirdly energetic and giddy and awkward music,” realizing that he “could not be depressed with it.” Out of all the other XTC works, that album “buoyed [him] up for when [he] needed to go out. It was a suit of armour [sic] for the outside world.” Another Anonymous says that the band “hasn’t miraculously healed, but it has definitely helped;” musician Quinn Fox rejoices (in Partridgean language) that “[XTC] guided me through the sharpest of thorns, thickest of thickets, and grizzliest of grasses;” Christie’s singer and bassist Kev Moore recalls that “these were dark days…Into that atmosphere, on the humble cassette, came English Settlement. I needed it more than I probably knew. I devoured this album.”

As for me, I’ve never relied on XTC for much spiritual rescue nor sociopolitical validation, but they (like the Talking Heads) lube my intellectual gears and put the “hip” in “unhip” – and vice versa. They don’t roll off the tongue, (literally) linguistically nor popularly, in average music discussions. They seem simultaneously timeless and dated, but always peculiar and (as much as I despise the term) quirky. Maybe they’re too British for their britches (or trousers), too fragrant for the funky, too smart for the hoi polloi. In a PopMatters article called “Is XTC Too Competent to Be Cool?” poet/teacher Kenneth E. Harrison asks: “How does it happen that such a creative, original band, with a career that lasted over 20 years and an output of more than 12 full-length albums, earn so little mention?” Harrison also notes “XTC’s absence from serious conversation about pop music,” and at the close of an excellent piece, he “hopes that XTC, at some point, will achieve a more prominent place, or for that matter any place at all, in the pop rock canon,” since the band’s catalog “is deeply sacred stuff.”

Let’s go with that. But the “sacred” is often antiquated and many treasured treasures are relegated to private and public collections, so I don’t resent any of XTC’s relative obscurity and low buzz among lowbrows. It’s the band’s lot, its nature, its proper place. “We’ve become a historical artefact that’s more important than when it was a pot in Cro-Magnon times,” said Andy Partridge. “As a museum exhibit it’s become priceless, but as a Neanderthal pot nobody wanted to bother pissing in it.” If What Do You Call That Noise? is anything like a museum, it’s a worthy exhibitor, and Mark Fisher is an apt curator indeed.

David Herrle